- Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Donald Crowhurst: The fake round-the-world sailing story behind The Mercy

- October 2, 2019

The mysterious and tragic disappearance of the single-handed sailor Donald Crowhurst more than 50 years ago continues to fascinate. Nic Compton explains why...

Hailed as a round the world single-handed hero, Donald Crowhurst in fact never left the Atlantic during his 243 days at sea. Photo: Alamy

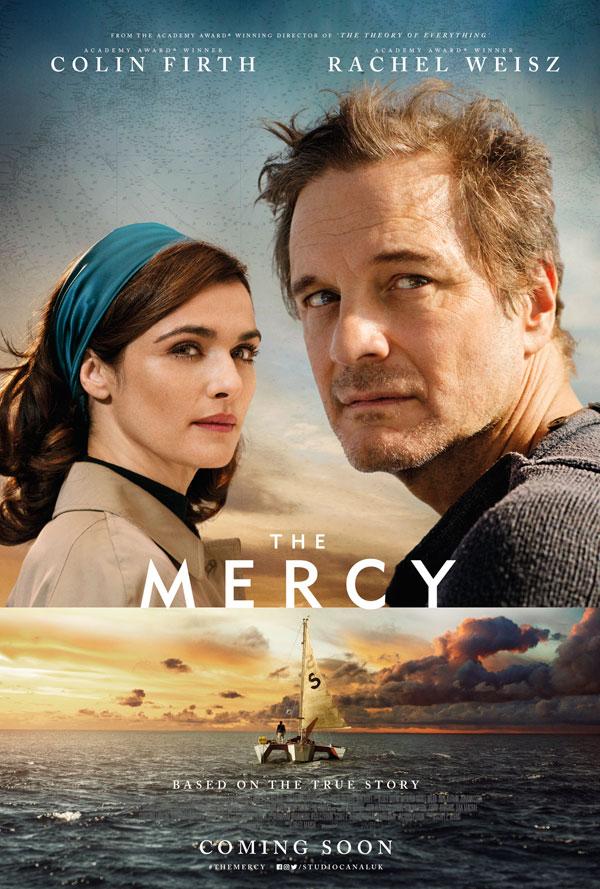

It was while I was researching my book about madness at sea in 2015 that I first heard a movie about Donald Crowhurst was in the works. Several websites published reports of a high-profile British feature starring Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz, and a few surreptitious photos of the cast filming off Teignmouth had been posted online. It seemed a lucky coincidence, given that my book would inevitably feature the Crowhurst story, but I assumed the movie would come out long before my book was ready.

Over the next couple of years, however, the release date for the film was repeatedly postponed – so much so that it became a running topic among Hollywood gossipmongers, who speculated that Crowhurst’s widow Clare had delayed progress, or that it was being held back to tie with the 50th anniversary of the events, or indeed that it might never be released in cinemas and go straight to DVD instead.

Meanwhile, I carried on writing my book, Off the Deep End , which was published in 2017, and the movie, The Mercy , was released in February 2018. There was never any doubt the tragic story of Donald Crowhurst would have to be included in any book about madness at sea.

Colin Firth stars as Donald Crowhurst in the 2018 film The Mercy . Photo: Studio Canal

Of all the stories I researched, it’s the one that has caught the public imagination most. Long before the latest Hollywood offering it inspired movies, books, plays, art installations, an epic poem and even an opera. Whereas many stories of adventures at sea seem to leave the general public cold, the Crowhurst tale continues to fascinate more than 50 years after Teignmouth’s most famous sailor vanished without trace. And yet, despite the thousands of words written about him, we really know very little more about him than we did 50 years ago.

It all started when Francis Chichester made his historic single-handed circumnavigation in 1966-67 – not the first to do so, by any means, but certainly the fastest up to that point, completing the loop in 226 days with just one stop, in Sydney, to repair his self-steering. Even before he’d docked at Plymouth there was a general realisation, which spread like osmosis throughout the sailing world, that the next step would be to sail around solo without stopping.

The challenge was turned into a contest by the Sunday Times which, in March 1968, announced two prizes: a Golden Globe trophy for the first person to sail round the world via the Three Capes single-handed and non-stop, and a £5,000 cash prize for the person to do it in the fastest time. The only stipulation was that competitors had to leave from a British port between 1 June and 31 October 1968, and had to return to the same place.

Article continues below…

A voyage for 21st Century madmen? What drives the Golden Globe skippers

A voyage for madmen, so was the original Sunday Times Golden Globe Race deemed. When the first non-stop race around…

How extreme barnacle growth hobbled the 2018-19 Golden Globe Race fleet

Eighty-knot gales, 10m-high waves, pitchpoling, loneliness and ever-depleting food reserves… of all the challenges facing a single-handed non-stop circumnavigator you…

Nine skippers eventually signed up for the race: the famous transatlantic rowing duo Chay Blyth and John Ridgway, who had by then fallen out but were sailing near-identical 30ft glassfibre production boats; Bernard Moitessier, already something of a legend in France for breaking the long-distance sailing record on his steel ketch Joshua; Moitessier’s friend Loïc Fougeron; Robin Knox-Johnston , an unknown British merchant navy officer sailing a heavy wooden boat called Suhaili ; two former British naval officers, Bill King and Nigel Tetley; the experienced Italian single-handed sailor Alex Carozzo; and Donald Crowhurst.

Out of the group, Crowhurst was by far the least experienced, the odd one out. Born in India in 1932, he went to Loughborough College after the war, until family nances and the death of his father forced him to cut his education short. He joined the RAF in 1948 but was chucked out after six years because of some high jinks with a vehicle; the same thing happened when he joined the army and he was forced to resign after he was caught trying to hotwire a car during a drunken escapade.

Persuasive character

Crowhurst with his wife Clare and their children Rachel, Simon, Roger and James, circa October 1968. Photo: Getty Images

Next he got as job as a travelling salesman for an electrics company, but was again dismissed after crashing the company car.

Ever-persuasive, he talked himself into a job as chief design engineer for an electronics company in Somerset, and in 1962 set up his own company, Electron Utilisation, to manufacture electronic devices for yachts.

The company got off to a good start, selling a simple but well-designed radio direction finder which Crowhurst dubbed the Navicator. Pye Radio invested £8,500 in the project, before getting cold feet and pulling out.

It quickly became clear that while Crowhurst was a charismatic personality and brilliant innovator he didn’t have the business acumen to run a successful company, and Electron Utilisation was soon in financial trouble.

Crowhurst managed to persuade local businessman Stanley Best to invest £1,000 to carry the company over what he assured him was a temporary lean period.

It must have been obvious to Crowhurst that he was heading for another failure. By now 35 years old, he could see the same pattern repeating itself, of high ambition thwarted by petty practicalities. Only, by now married to Clare with four children and living in a comfortable house outside Bridgwater in Somerset, the stakes were higher than ever.

His response to failure was to reinvent himself yet again. This time he would become a record-breaking sailor, a seafaring hero in the vein of Chichester: he would sail around the world single-handed – even though he had until then only dabbled in sailing, mainly on board a 20ft sloop called Pot of Gold . First, however, he needed a boat.

After failing to persuade the Cutty Sark Committee to lend him Gipsy Moth IV for the voyage, he decided a trimaran would be the ideal craft – despite having never sailed on one. To get the funding to build his dream boat he achieved perhaps the greatest coup of his life.

With Electron Utilisation going down the pan, his backer Stanley Best wanted his loan repaid, but Crowhurst managed to persuade him the best way to get his money back would be to fund the construction of the new boat.

A replica of the 41ft Teignmouth Electron used in the filming of The Mercy . Photo: WENN Ltd/Alamy

The crux of his argument was that he would use the trimaran as a test bed for his new inventions, and the publicity gained from entering the race would catapult the company to success. The sting in the tail was that the loan was guaranteed by Electron Utilisation, which meant that, if the venture failed, the company would go bankrupt.

To understand how he managed this turnaround you have to go back in time. Photos of Crowhurst make him look geekish and uncool to the modern eye. With his sticky-out ears, high forehead, curly hair, tie and V-neck jumper, he appears the epitome of the eccentric inventor.

But all the contemporary accounts describe him as a charismatic, vibrant personality, the sort of person who lights up a room when they walk in – as well as being extremely clever. In fact, his cleverness was his problem. He had the gift of the gab and, once persuaded of something, could talk anyone into believing him.

“This is important,” said his wife Clare. “Donald had this definite talent. He would say the most amazing things, but then no matter how crazy they seemed, he’d be clever and ingenious enough to make them come true. Always. This is a most important point about his character.”

Crowhurst’s widow, Clare, holds the last photograph taken of Donald with his family. Photo: Guy Newman / Alamy

Slow off the mark

So Crowhurst got the money for Teignmouth Electron , which was built by Cox Marine in Essex and fitted out by JL Eastwood in Norfolk. It’s a measure of how far behind he was that by the time the Cox yard started building the hulls towards the end of June, Ridgway, Blyth and Knox-Johnston had already set off on their round-the-world attempts. In the event, complications meant the launch date was delayed and even when Crowhurst finally set off on 31 October – just a few hours before the Sunday Times deadline expired – his boat was barely complete.

None of the clever inventions he had devised for the boat were connected, including the all-important buoyancy bag at the top of the mast, which was supposed to inflate if the trimaran capsized. His revolutionary ‘computer’, which was supposed to monitor the performance of the boat and set off various safety devices, was no more than a bunch of unconnected wires.

Worse still, he had had to borrow yet more money from Best to finish the boat, and had mortgaged his home to guarantee the loan. Crowhurst made a desultory figure scrambling about the deck of his trimaran as he set off on his great adventure – only to turn around within a few minutes to untangle his jib and staysail halyards, which were snagged at the top of the mast.

It was just the start of his troubles. After two days at sea, while still within sight of Cornwall, the screws started falling off his self-steering and, not having any spares on board, he had to cannibalise other parts of the machine to replace them.

A leaky boat

A few days later, halfway across the Bay of Biscay, he discovered the forward compartment of one of the hulls had filled up with water from a leaking hatch.

Soon, other compartments began to leak and, as he’d been unable to get the correct piping for the bilge pumps, his only option was to bail them out with a bucket. Then, two weeks after leaving Teignmouth, his generator broke down after being soaked with water from another leaking hatch.

“This bloody boat is just falling to pieces due to lack of attention to engineering detail!!!” he wrote in his log. A few days later he made a long list of jobs that needed doing and concluded his chances of survival if he carried on were at best 50/50. He began to think about abandoning the race.

But Crowhurst was in a triple bind. If he dropped out at this stage, not only would his reputation be destroyed but his business would go bankrupt and, perhaps worse of all, he and his family would lose their home. For all these reasons, giving up was not an option.

It soon became clear his estimates for the boat’s speed had been wildly optimistic: he had estimated an average of 220 miles per day, whereas the reality was about half that, on a good day. There was no way he was going to catch up with the other competitors or win either of the prizes, unless something extraordinary happened.

And so, just five weeks after setting off from Teignmouth, Crowhurst started one of the most audacious frauds in sailing history: he began falsifying his position. From 5 December, he created a fake log book, with accurately plotted sun sights, working back from imaginary positions.

To make it look convincing, he listened to forecasts for the relevant areas and wrote a fictional commentary as if he was experiencing those conditions. It was quite a feat of seamanship, and only someone of Crowhurst’s brilliance could have carried it off convincingly.

The great deception

After a few days’ practice he felt sufficiently confident to send his first ‘fake’ press release, claiming he’d sailed 243 miles in 24 hours, a new world record for a single-handed sailor. In fact, he’d actually sailed 160 miles, a personal best perhaps, but certainly no world record.

And so the great deception began. As Crowhurst slowly worked his way down the Atlantic, his imaginary avatar was already rounding the Cape of Good Hope and heading into the Indian Ocean. Gradually, partly through misunderstandings and partly due to the spin added by his agent back in the UK, Crowhurst’s positions became ever more exaggerated, until it looked like he might win the race after all.

Meanwhile, the real Crowhurst was pottering around the Atlantic – ‘hiding’ in exactly the same area he had, only a few weeks earlier, jokingly suggested a sailor might hide to falsify a round-the-world voyage. To make sure his radio signals weren’t picked up by the wrong land stations, he maintained radio silence for nearly three months, from the middle of January until the beginning of April, which he blamed on his generator breaking down again.

Teignmouth Electron was found drifting in mid-Atlantic, 700 miles west of the Azores, on 10 July 1969

Unbelievably, he even put ashore in a remote bay near Buenos Aires in Argentina to buy materials to repair one of the hulls, which had started to fall apart. Despite being greeted and logged by local officials, this rule-breaking stop remained undetected.

On 29 March he reached his most southerly point, hovering a few miles off the Falklands, 8,000 miles from home, before starting his ascent up the Atlantic.

Finally, on 9 April, he broke radio silence and exploded back into the race with a telegram containing the infamous line: “HEADING DIGGER RAMREZ” – suggesting he was approaching Diego Ramirez, a small island southwest of Cape Horn (in reality, he was just off Buenos Aires).

By this time Moitessier had had his ‘moment of madness’ and had dropped out of the race and was sailing to Tahiti ‘to save his soul’. The only other competitors left were Knox-Johnston, who was plodding slowly up the Atlantic and on track to be the first one home, and Tetley, racing in his wake to pick up the prize for the fastest voyage.

Rachel Weisz plays Clare Crowhurst in The Mercy

It seems likely that Crowhurst was planning to finish a close second to Tetley, which would save him from financial ruin without drawing too much attention to his fraudulent log books.

But his reappearance in the race had a dramatic effect on the course of events. Already nursing a broken boat up the homeward leg of the Atlantic, Tetley worried he might lose the speed record to the resurgent Crowhurst, and started pushing his trimaran faster towards the finish line. Some 1,100 miles from home, the inevitable happened: Tetley’s boat broke up and sank, and he had to be rescued by a passing ship.

Suddenly, the spotlight shifted to Crowhurst, the unlikely amateur who’d apparently come out of nowhere to beat the professionals. The BBC had a crew on standby to record his homecoming and hundreds of thousands of people were expected to throng the seafront at Teignmouth to welcome him home.

It was everything Crowhurst dreaded. As one of the winners, his books would come under much closer scrutiny – and indeed there were already some, including race chairman Francis Chichester, who suspected something wasn’t quite right.

In the middle of June, Crowhurst reached the Sargasso Sea and, as the tradewinds died and his boat slowed down, he descended into a mental quagmire of his own. It was as if all his previous failures had caught up with him in this one grand, final failure.

Teignmouth Electron on Cayman Brac in 1991. The wreck has deteriorated considerably since. Photo: Geophotos / Alamy

And this time there was no way out, no way of reinventing himself. Instead, he gave up ‘sailorising’ and resorted to philosophising instead. Over the course of a week, he wrote a 25,000-word manifesto that described how mankind had achieved such an advanced evolutionary state that it could now merge with the cosmos. All that was needed was ‘an effort of free will’.

He ended his journal on 1 July with this desperate appeal: ‘I will only resign this game / if you agree that / the next occasion that this / game is played / it will be played / according to the / rules that are devised by / my great god who has / revealed at last to his son / not only the exact nature / of the reason for games but / has also revealed the truth of / the way of the ending of the / next game that / It is finished / It is finished / IT IS THE MERCY’

There then followed a countdown, ending at 11:20:40 precisely. It’s not known what happened next, but it’s generally assumed Crowhurst jumped over the side of the boat to his death. His empty yacht was found by a passing ship on 10 July with two sets of log books on board: the real and the fake.

It was left to Sunday Times journalists Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall to piece together what had happened and to reveal to the world Crowhurst’s elaborate hoax. With Crowhurst and Tetley both out of the race, Knox-Johnston, on his slow wooden tortoise of a boat, was the only person to finish the race and was duly award both prizes – though he subsequently donated the £5,000 cash prize to Crowhurst’s widow.

Huge public interest

The Golden Globe race generated enormous public interest at the time, and the discovery of Crowhurst’s boat was front page news. It’s a fascination that has continued almost unabated to this day. The French film Les Quarantièmes Rugissants , based on the Crowhurst story, was released in 1982, while at least five plays have picked up the theme, as well as the 1998 opera Ravenshead.

In 2006, the acclaimed documentary Deep Water incorporated contemporary footage of the race, including some shot by Crowhurst during his voyage, and in 2017 director Simon Rumley released his own stylised take on the story, called simply Crowhurst.

The Mercy , then, is only the latest take on the Crowhurst saga – although with Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz on board, it is the most high-profile. So how does it compare to previous efforts?

As you’d expect of such a mainstream movie, the focus is firmly on the psychological drama rather than on the sailing – which is probably just as well considering how often films get the details of sailing wrong. There are some minor errors – Chichester wasn’t the first person to sail around the world single-handed, and the prize for the first competitor to finish the race was a trophy, not £5,000 – but the sailing scenes are generally quite convincing.

More importantly though, The Mercy is a captivating psychological drama, which shows how, through a series of small steps, a person can box themselves into a corner from which there is no escape. It’s this humbling of a deluded but essentially well-meaning man that gives the story such resonance and has inspired artists and writers for more than five decades. For, as anyone who has sailed out of sight of land knows, the sea has a knack of bringing out our inner demons. There is a Crowhurst in us all.

First published in the March 2018 edition of Yachting World. The Mercy is available to watch on BBC iPlayer until 11 Jan 2021 .

Stay up to date with notifications from The Independent

Notifications can be managed in browser preferences.

UK Edition Change

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Car Insurance deals

- Lifestyle Videos

- UK Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Home & Garden

- Broadband deals

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Solar Panels

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Betting Sites

- Online Casinos

- Wine Offers

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

Drama on the waves: The Life And Death of Donald Crowhurst

In 1968 an amateur sailor set off on the inaugural solo round-the-world yacht race. incredibly, he appeared to be leading the race until the closing stages when he disappeared and was never seen again. now the tragic truth about this very british hoaxer is being told. ed caesar reports, article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails, thanks for signing up to the breaking news email.

For the past week, Britain has been in the thrall of an extraordinary sporting challenge. Within 24 hours of the start of the Velux 5 Oceans, a three-stage solo round-the-world yacht race starting in Bilbao, four sailors were forced to return to port, so horrific were the conditions off the coast of Spain. It was a reminder, if one were needed, that a solo circumnavigation of the globe remains the Everest of sporting achievements. Sir Robin Knox-Johnston - who, at 67, is the Velux 5 Oceans' oldest competitor - called the Bay of Biscay's 40ft waves and high winds "boat-breaking".

He should know. In 1969, without the global positioning systems, or support crews, or the corporate sponsorship with which modern single-handers put to sea, Knox-Johnston became the first person to complete a non-stop solo circumnavigation on his boat Suhaili, winning the inaugural Sunday Times Golden Globe Race in the process. "In 1969, my only advance weather system," said Knox-Johnston last week, "was a barometer from the wall of a pub".

But as remarkable as Knox-Johnston's feat was, it will forever be eclipsed by the plight of one of his fellow competitors in that first race: Donald Crowhurst, a 36-year-old English businessman, who went to sea in a leaky boat and committed suicide in the Atlantic 243 days later. Now, splicing harrowing onboard audio and visual footage of Crowhurst with interviews of the sailor's friends and family, a film, Deep Water, tells the story of Crowhurst's last voyage, and his descent into madness.

A former RAF pilot with a small, ailing electronics business called Electron Utilisation, Crowhurst was, at best, an enthusiastic weekend sailor. He was also married and a father of four children. So what convinced him he should go to sea for nine months is anyone's guess. But not only was Crowhurst determined to enter the race, he was determined to win.

To understand Crowhurst's peculiar obsession with competing in this gruelling race, one needs to know that in 1968, Britain was in the grip of sailing fever. The previous year, Sir Francis Chichester had achieved the then monumental feat of sailing around the world, on his own, punctuated only by a stop in Australia. In the era of the space race, when the possibilities of human endeavour seemed limitless, the world lapped up the heroism of Chichester's achievement, and 250,000 people lined the south coast to cheer him home.

The Sunday Times, which had reaped the rewards of sponsoring Chichester's journey, was looking for a way to continue tapping into the appetite for maritime derring-do. The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race was born. Using the clipper route, from Britain, through the Atlantic and round the Cape of Good Hope; through the Indian and Pacific Oceans; round Cape Horn and back to Britain, the competition was billed as a test for the world's greatest yachtsmen.

But, to encourage entrants, no evidence of sailing experience was required, and competitors were allowed to set off any time before 31 October. A trophy for the first man to complete the course, and a separate prize of £5,000 for the fastest time, would be awarded. Out of the nine men who set off in 1968, only one, Knox-Johnston, finished.

Crowhurst's bid to win the Golden Globe always looked precarious. In the months before the race, the businessman had become convinced that by coupling a new, triple-hulled boat design with his own technological innovations (a self-righting mechanism in case of capsize, for instance), he could win. With the financial support of a local businessman, Stanley Best, Crowhurst bought and developed his vessel. But Best's money came with a proviso: if Crowhurst failed to finish the race, he would have to pay for the boat himself.

To make matters more complicated for Crowhurst, he fell into the hands of one of Fleet Street's more manipulative press officers, Rodney Hallworth, who knew Crowhurst was journalistic manna. Hallworth sold him to the press as a plucky, English amateur with incredible prospects of bringing home the big prize. All the while, the deadline for starting the race, 31 October, was creeping round, and Crowhurst was struggling to make his boat, the Teignmouth Electron, seaworthy.

The day before his voyage began, Crowhurst made last-minute preparations on the Electron, then retired to a hotel with his wife, Clare. That night, he broke down in tears. The boat, he knew, was not ready. But he also knew it was too late to pull out. Hallworth would not allow it. Best would want his money back. The family would be ruined.

Crowhurst set sail the next day with unsorted provisions and vital equipment strewn across the deck of the Electron. And, even at this early stage, calamity loomed. He was forced to return to harbour in the first minutes of his journey when an anti-capsize air-bag got caught in the rigging.

Over the next two weeks, Crowhurst made slow progress. As Knox-Johnston and the Frenchman, Bernard Moitessier, who had set off weeks earlier, neared New Zealand, Crowhurst was languishing in the North Atlantic. At least he was afloat. Four men - John Ridgway, Loick Fougeron, Bill King and Alex Carozzo - retired before they reached the Indian Ocean. Of the four who remained, one Englishman, Chay Blyth, who set off with no sailing experience, retired in East London, South Africa. Another, Nigel Tetley, was making good time ahead of Crowhurst.

But if Crowhurst's slow times were worrying, they were as nothing compared to the anxiety he felt about the state of his boat. The Electron had started to leak, and her skipper faced a dilemma. Should he continue into the Southern Ocean, where his boat would almost certainly sink? Or should he return home to face shame and financial ruin?

In the end, Crowhurst did neither. Instead, he started to radio a series of incredible positions and speeds to Hallworth, who, in turn, embellished the lies and sold them to Fleet Street as fact. Suddenly, Crowhurst seemed to have a genuine chance of scooping the prize for the fastest circumnavigation.

The truth was that the difference between Crowhurst's real and stated positions was growing by the day, a discrepancy he kept track of by recording two logbooks. But this ruse only exacerbated his problems. Because of the frailty of the Electron, Crowhurst could not enter the perilous Southern Ocean. Neither could he return home, where ignominy and bankruptcy awaited. All the while, his wife, his four young children, and the rest of the world thought he was sailing into the record books.

Faced with an insoluble problem, Crowhurst did the only thing he could think of; he stayed put. Bobbing around in the Atlantic off Brazil, Crowhurst scrupulously filled out his fraudulent logbook, and cut off all radio contact with the world for three months. At one point, he was forced to pull into an Argentine fishing port to make vital repairs to his boat, an action that in itself would have been enough to disqualify him from the race. Still, Crowhurst kept up his pretence.

His fellow competitor, Moitessier, disillusioned about competing in a commercially motivated event, had rejected the idea of finishing the race at all. Instead, he simply to kept on sailing, eventually dropping anchor in Tahiti, after one and a half laps of the globe. Knox-Johnston arrived back in England to a hero's welcome. He had won the trophy for coming in first. But he had made slow time, a leisurely 312 days. In the eyes of the world, the race was now on between Tetley and Crowhurst to see which man would win the race for the £5,000.

The thought of winning terrified Crowhurst. He knew that if he came home in the fastest time, his logbook would be subject to scrupulous checks by the Golden Globe judges and the press. He determined on making a slow journey across the Atlantic, so Tetley would win the prize, and he could come in a dignified, unheroic second. Re-establishing radio contact with Hallworth for the first time in 12 weeks, Crowhurst confirmed he would not be able to catch Tetley. Still, his family and friends, who had been fearing the worst for Crow-hurst, were relieved that he was, apparently, safe and well.

Crowhurst's scheme was looking good. In May 1969, he began to make for home, his faked journey matching his real one for the first time in months. Then, disaster. Tetley, thinking Crowhurst was hot on his heels, had pushed his boat too hard, and sunk in the Azores. Crowhurst was going to win the prize.

The news of Tetley's sinking affected Crowhurst profoundly. He drifted deep into depression, refusing to sail, and took to his logbook. As he lolled in the mid-Atlantic, Crowhurst wrote a 25,000-word treatise on time travel and divinity. He counted down his remaining hours on Earth, believing death would not only be "the mercy" but that it would transform him into a "cosmic being". On 29 June 1969, after 243 days at sea, Crowhurst made one last entry into his logbook. His self-allotted time had come. This was "the mercy" he had been praying for. His boat was found 12 days later, with logbooks recording his genuine position and grainy sound and video recordings unharmed. It has since been assumed Crowhurst took the logbook of his fraudulent positions with him as he threw himself overboard. Back in Britain, Knox-Johnston was awarded the £5,000 for the fastest time, which he donated to the Crowhurst family, and Tetley was given a consolation prize. For unknown reasons, Tetley committed suicide a year later.

Deep Water's co-producer, Al Morrow, said: "What I felt about Donald was that although not all of us would go to sea, the situation was one that any of us could have got ourselves into. You tell one tiny little lie, and that turns into another lie, and suddenly there's no way out. The other thing that really struck me about the story is that being on your own for nine months at sea is such a unique thing. You have no one to speak to. He must have been so lonely."

Her fellow producer, Jonny Persey, added: "I recognise [Crowhurst's story] could arouse feelings of anger. He could have done the right thing any number of times. He had those opportunities, but every decision he made was wrong. It was very hard for his family to contribute to this film, but they have come to a point where they understand what happened, and recognise the complexity of what was going on with Donald."

The first screening of Deep Water, with the creative team and the family, was a charged occasion, says Morrow. "I was terrified," she admits. "The family had been so supportive through the process, but they had to trust us with the direction the film was going in. Clare's daughter, Rachel, walked out a few times in the screening, because she found it too emotional to sit through."

Another person in whom Deep Water will strike a resonating chord is Knox-Johnston, himself an interviewee for the film. Unable to attend any preview screenings, he has taken a DVD of Deep Water on his Velux 5 Oceans boat, Saga Insurance. When he finds a spare two hours away from racing, he will watch Crowhurst's story, all alone at sea.

Deep Water is released on 15 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Want an ad-free experience?

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

Accessibility Links

Colin Firth plays Donald Crowhurst in The Mercy, the film about his round-the-world yacht race

The strange tale of donald crowhurst and his attempt at the sunday times round-the-world yacht race is brought to life in a new film with colin firth. by jeff dawson.

I t says something about diverging postwar fortunes that, in 1969, while America feted Neil Armstrong, Britain was crossing its fingers for the amateur yachtsman Donald Crowhurst. A 36-year-old father of four, Crowhurst was the antithesis of a buzzcut adventurer. Brow furrowed, baggy-jumpered, he was better known in Bridgwater, Somerset, as a struggling inventor, knocking up marine navigation equipment in his shed.

Yet, that April, there he was, breaking radio silence to announce that his trimaran, Teignmouth Electron, had successfully rounded Cape Horn and was steering a course for home. He didn’t know it yet, but he looked set to complete the fastest non-stop solo circumnavigation of the Earth.

A “weekend sailor” with no ocean-going experience, Crowhurst had been an unlikely entrant in The Sunday Times

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Crowhurst review – tormented sailor's heartbreaking voyage

Justin Salinger gives a superb performance as the guilt-ridden yachtsman lost in a hellish nightmare at sea, in the wake of Colin Firth’s starrier take on the same true story

J ust last month, we had a new movie entitled The Mercy , starring Colin Firth, about the strange true story of amateur British yachtsman Donald Crowhurst who entered a round-the-world sailing competition in 1968, started radioing in fake coordinates when the going got rough and finally took his own life at sea, overwhelmed with loneliness and guilt.

That wasn’t a bad film, by any means, but here is a second one on exactly the same subject, from the indie horror director Simon Rumley. It is frankly superior in every way. By getting inside Crowhurst’s head, and giving a nightmarish, impressionistic account of what he finds there, Rumley really nails Crowhurst’s naive ambition and his terrible fear. With long, detailed wordless sequences, he solves the problem of how to portray Crowhurst’s solitary existence on the boat – all of this in a way that The Mercy never came anywhere near.

The details are tremendous – the baked beans, the toothpaste, the little foot pump that squirts freshwater into his kettle. It looks very much like the caravanning holiday from hell, and casts a weirdly convincing new light into why a caravan entrepreneur should want to sponsor Crowhurst in the way that he did.

Justin Salinger is absolutely superb in the lead role, heartwrenchingly convincing as the decent British chap who wears pyjamas as he goes to bed on board his boat every night: thin, clenched, wiry, doggedly making the best of it. Salinger exposes how miscast Firth actually was in the role, honest and heartfelt though Firth’s performance was. With a lower budget but a much fiercer, and more intuitive grasp of the material, Rumley has made a tremendously good and moving film.

- Drama films

Most viewed

What really happened to sailor Donald Crowhurst on the voyage that inspired The Mercy?

Acclaimed director James Marsh reveals his theory about the tragic Brit played by Colin Firth

- Thomas Ling

- Share on facebook

- Share on twitter

- Share on pinterest

- Share on reddit

- Email to a friend

What sort of a man was Donald Crowhurst, the amateur sailor who set off around the world alone never to be seen again?

A vainglorious chump who abandoned his wife and four young children in reckless pursuit of his own impossible dream? Perhaps a man wounded by past failures who wanted to prove to that family he was worthy of their pride?

Or a delusional fantasist – someone whose desire to be noticed cost him his life, robbing his wife of a husband and his children of a father?

- The Mercy review: a compelling story told with care and compassion

- Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz on the harrowing true story behind new film The Mercy

Most likely, a little bit of all the above. Which is why Crowhurst’s life, and death, have so fascinated writers and filmmakers ever since he plunged over the side of his small trimaran during the first nonstop, round-the world yacht race in 1968-69 (a race ultimately won by the only finisher, Robin Knox-Johnston).

Here was a man who lied about his position in the race – a competition he was disastrously ill-equipped to take part in – realised his fraudulent actions would be uncovered and, rather than face the music at home, took his own life.

More like this

Or did he? Director James Marsh (a Bafta winner for documentary Man on Wire and the Stephen Hawking biopic The Theory of Everything) has another theory that extrapolates the written evidence found on Crowhurst’s boat, showing that the amateur sailor had totally lost his mind.

“Clearly, the pattern of agony you see in the logbooks suggests that he really is on a path to self-destruction, and that’s one very obvious way of interpreting what happens. The second is that it was simply an accident and he may have just slipped and fallen off the boat. And the third possibility is one that I think intrigued Colin and I more than anything else.

“We felt that in his final writings he was constructing a different version of reality for himself to enter into and he may well have believed he was going somewhere else when he stepped off the boat. But, clearly, the logbooks do suggest a huge mental crisis.”

The “Colin” in question is Colin Firth, who plays Crowhurst in Marsh’s new film The Mercy, a title that takes its name from the sailor’s maniacal final writings.

“The last words written in his logbook are ‘It is the mercy,’ which feels like a kind of idea of a release from all his torment,” says Marsh.

Both he and Firth would be the first to admit that this is a sympathetic evocation of Crowhurst’s decline and fall (his abandoned boat, the Teignmouth Electron, was found drifting in the mid-Atlantic more than eight months after he’d set off from south Devon).

Both feel that history has been unkind to him. “What you see is a man under enormous pressure,” says Marsh. “You know that he shouldn’t be going. He hadn’t prepared well enough and the boat was not fully seaworthy.”

But Crowhurst did put to sea. After struggling with faulty equipment, he fell behind in the race and, aided and abetted by his PR man back in Devon (brilliantly played by David Thewlis), began falsifying his race position.

The fact that Crowhurst was, as Marsh describes, “a good father and husband” makes the tragedy even more unsettling.

“That was what he betrayed,” says the director. “He doesn’t return to the people he loves because he can’t, and that has blighted their lives. I think some of that is the unravelling of his mind because of all those months of isolation at sea, and under the burden of these decisions that he’s made about cheating. I think he would say, ‘I’ve brought disgrace upon my family and maybe it’s better not to come back at all.’”

Crowhurst’s wife is played by Rachel Weisz. She says of her character, “I sense that Clare loved Donald very deeply and she didn’t want to stop him living out his dreams.”

The real-life Clare, now in her 80s, never remarried after her husband’s death and, remaining protective of his memory, is wary of the attention of this new film (in cinemas from Friday 9 February).

“I don’t think they’re particularly ready to welcome another telling of this tale, and who can blame them?” says Marsh. “It’s a private family tragedy that on a regular basis seems to get into the news, even after all these years. I don’t think it’s something that any of us would like if it were our family. But from what I can gather, they’ve seen the film and do regard it as a sympathetic telling of Donald’s story.”

Sympathetic it unquestionably is. But in attempting to rehabilitate the reputation of Crowhurst, is Marsh guilty of rewriting history?

“The thing is, I don’t think he was guilty of some grand conspiracy to cheat. He falls into it step by step, which is how most terrible things done by decent people tend to happen. You gradually get yourself into a situation that you can’t get out of. I really sympathise with that. I understood it from a personal point of view and wanted to give the most forgiving account of that process.

“If it were me, I would have turned back and gone straight to my family and said, ‘I’ll deal with the humiliation.’ There were contradictions that you can’t really reconcile, but that’s true of any complicated person.”

The Mercy is in UK cinemas now

- Discover the delightful South Devon town at the heart of The Mercy - Teignmouth

Subscribe to Radio Times

Try 10 issues for just £10!

Transform your later life

Unlock the cash tied up in your home to pay off debts or help your family, says Paul Lewis. Get the free guide written by Paul Lewis

Save on heathcare

Compare quotes for healthcare insurance from AXA, Aviva, Bupa and more with Confused

The best TV and entertainment news in your inbox

Sign up to receive our newsletter!

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy . You can unsubscribe at any time.

'It is the mercy'

Donald Crowhurst's last diary entry before he disappeared overboard. Carving by Tacita Dean

07 Feb 2018

The Mercy starring Colin Firth portrays Donald Crowhurst's tragic attempt to sail around the world single-handedly in the first race of its kind. Maritime specialist Jeremy Michell sheds light on the perils of sailing alone, the progress of yacht racing, and the importance of remembering failure.

By Kate Wilkinson

Visit the National Maritime Museum

The thrill of the race

Fifty years ago, the Sunday Times Golden Globe became the first solo non-stop round-the-world yacht race. Building on the international celebrity of Francis Chichester’s circumnavigation in 1966-67, the UK newspaper launched a sailing event to capture the world’s imagination – the ultimate competition of skill and endurance, and open to anyone, amateurs included.

'Yacht racing in this country has always been big, but it tended to be fairly elitist in the past,' says Jeremy Michell, a sailing instructor and part of the National Maritime Museum’s curatorial team, 'The Golden Globe opened up in a more popular mind the idea that people who are not wealthy could go and take part.'

Yachting really began when King Charles II brought his enthusiasm for the activity to England on return from exile in 1660 and raced yachts down the Thames against his brother for huge wagers. In the late 1870s, Lord Brassey achieved the first circumnavigation by a private yacht, building himself a steam-assisted three-masted schooner called 'Sunbeam' and sailing round the world with his family. The boat's figurehead is on display in the National Maritime Museum.

The Golden Globe opened up in a more popular mind the idea that people who are not wealthy could go and take part.

Struggling businessman and sailing amateur Donald Crowhurst was the classic underdog when he entered the 1968 competition. Putting everything into the race, he had signed a contract with his sponsor whose penalty clause meant that he would forfeit his house and business if he didn’t finish.

A doomed adventure

Crowhurst waved goodbye to his wife and four children on the race’s last eligible day aboard the Teignmouth Electron, a trimaran he had barely sailed before setting off. He had planned to equip the vessel with his own safety features, the success of which he hoped would revive his business in maritime navigational technology, Electron Utilisation Ltd. But he hadn’t completed the work before leaving British shores, leaving him in the process of tweaking while sailing.

It didn’t take Crowhurst long to realise how perilously ill-equipped he would be to tackle the waves of the Southern Ocean. If he continued he could die, but quitting would ruin him financially.

For a while it seemed like the plucky amateur could steal the race when Crowhurst started reporting false coordinates showing incredible gains in distance. The deception ended when after weeks alone at sea under immense physical, personal, and financial pressure, he committed suicide. This seemed the most likely cause of his disappearance: when rescuers found his abandoned trimaran, they discovered log books and reams of diary entries showing a collapsing mind.

Crowhurst’s tragedy caused a worldwide sensation. The Sunday Times Golden Globe didn’t run again, and its winner, Robin Knox-Johnston donated his £5,000 winnings to Crowhurst’s grieving family. Knox-Johnston was the only entrant to complete the race, with the other entrants forced to retire along the way.

Solitude at sea

Crowhurst’s behaviour was seen by many as foolish and reckless. He was certainly underprepared, and his false reporting put unnecessary pressure on his fellow competitors. One bad decision followed another, and he was soon lost in a nightmare predicament. How could he let things go so wrong?

Michell says it’s important not to underestimate both the physical and mental challenge of a solo voyage: 'Unless you have done that sort of race, it’s very difficult to make a judgement call as to what the trigger points are to make someone lose their mind in that way and potentially commit suicide.'

Alone at sea, you might catch about 20 minutes of sleep before you’re up again doing something. Performing the roles of a whole crew, you have to be mentally alert all the time. A small change of sound on the boat might wake you up.

Unless you have done that sort of race, it’s very difficult to make a judgement call as to what the trigger points are to make someone lose their mind in that way and potentially commit suicide.

Not only that, without anyone to talk to, 'you’ve got no one to relieve any emotional issues you might have, whether that’s frustration, anger, sadness, loneliness.' Michell knows those who have sailed long distances on their own. During one transatlantic voyage, a friend would call any ship he saw just for the sake of another voice (as well as to confirm his position with their navigation): 'He said you could end up in tears over the most stupid things because it’s the only emotional release you have.'

Though at home it might seem bizarre, when you’re on your own it’s a very different emotional experience, Michell says.

21st Century racing

Though the stakes are high, sailing around the world single-handedly continues to present an appealing challenge. Yachting is as popular as ever and there have been numerous successful racing events world-wide.

What has changed in yacht racing between now and Crowhurst’s day?

Michell lists the improvements to on board technology: the use of hydraulics to keep the yacht stable, electronic equipment for winches, hoisting and dropping sails. Most importantly, there’s the communication. Satellite telephones and beacons allow people to know where you are. In short, 'there’s a lot more of a safety net,' Michell says.

Today it would be unimaginable for a sailor of Crowhurst’s limited experience to take part in such a demanding voyage. The Vendée Globe, a single-handed non-stop round-the-world race founded in 1989, requires its entrants to undertake survival training before participating.

Commemorating failure

Royal Museums Greenwich plays host to some of the most dramatic, awe-inspiring, and successful maritime stories through the objects on display and in conservation. John Harrison’s 18th Century marine timekeepers in the Royal Observatory were the first instruments to solve the problem of finding longitude at sea.

Also in our collection is Donald Crowhurst’s ‘Navicator’ , which he produced and took with him on his doomed voyage. On free display in the Queen’s House is a series of striking photographs by artist Tacita Dean, of Crowhurst’s abandoned trimaran on the coast of the island Cayman Brac. In the National Maritime Museum you can find the artist's carving, of the words 'It is the mercy', which refer to Crowhurst's final diary entry.

So why do we preserve the memory of such a sad event in maritime history?

'It’s always good to remember that life isn’t one long successful winning streak,' Michell says, 'it was never obvious that Britain would be a top maritime nation: it happened through incidences, setbacks, circumstances, failures and successes. In terms of sailing and our yachting industry, it’s exactly the same.'

Crowhurst’s story is a useful reminder of the dangers of yachting, and would have made an impact on the regulation of similar racing events since 1968. 'Out of failure can come some kind of success that makes it safer for other people,' Michell says.

The race’s revival

2018 marks the 50th anniversary of that first ill-fated race. Following a number of books and documentaries over the years, Colin Firth plays Crowhurst in the upcoming film, The Mercy, which is set to fascinate audiences anew. In an earlier preview of the film last year, Robin Knox-Johnston expressed his satisfaction with the film in an interview with Yachting & Boating World magazine.

Later in the year, the Golden Globe race will be re-launched to test sailors under the same circumstances that Crowhurst and Knox-Johnston faced. No modern satellite technology is allowed for navigation – instead competitors must use their skills with instruments such as sextants to make the necessary calculations to steer a good course.

As a safety measure, the race’s website states that:

'All entrants will be tracked 24/7 by satellite, but competitors will not be able to interrogate this information unless an emergency arises and they break open their sealed safety box containing a GPS and satellite phone.'

Also unlike the original race, entrants must show prior ocean sailing experience of at least 8,000 miles and another 2,000 miles solo.

In July the competitors will set off for a challenge like no other.

Even after 50 years, the events of 1968 continue to both haunt and inspire the world’s imagination.

Banner image: 'It is the mercy' by Tacita Dean, courtesy of the artist and Frith Street Gallery.

Become a member

Member benefits include events such as the exclusive preview screening of The Mercy on 8 November, arranged with STUDIOCANAL, a day before the official cinema release.

Find out more

E ight-year-old Simon Crowhurst huddled in a big, strange bed, listening to the waves batter the coastline while the wind moaned outside his window. His family was staying in a hotel in Teignmouth, on the southern toe of England, because tomorrow his father, Donald, was setting off to sail around the world. But as Simon listened to the weather rage, the excitement he’d felt over his father becoming a real-life adventure hero collapsed. He had seen his father’s spindly 12-metre boat, and for the first time, it occurred to him that this voyage was dangerous. Simon was terrified.

In a nearby room, Donald Crowhurst’s confidence was crumbling into tearful panic as he confessed to his wife, Clare, that his boat wasn’t ready. Only later would it occur to her that he may have been begging her to tell him not to go, to give him a way out. The thought would haunt her. But at the time, even with her normally ebullient husband sobbing in front of her, she still believed he could do anything and didn’t want him to regret giving up. So Clare did for Crowhurst what she’d been doing for their children, 10-year-old James, seven-year-old Roger, five-year-old Rachel, and Simon: She stuffed her fear down deep and told him everything would be fine.

The next day, Oct. 31, 1968, Simon was relieved to see the weather had calmed. His excitement returned, buoyed by the news cameras and onlookers milling around. He and his family boarded his father’s boat, the Teignmouth Electron–named as a publicity nod to the resort town from which he was sailing and his own struggling electronics business—to say goodbye. Crowhurst kissed each of his children on the forehead and told James and Simon to look after their mother. Simon would always remember the undulating sea beneath his feet as he stood on the deck of another boat with his family, watching his father and the Electron get smaller, then slip over the horizon and disappear.

Donald Crowhurst, 36, was about to became a British folk hero, the middle-class family man who conquered the seas and captivated the nation. Later, he would be seen as a con man who claimed to have sailed around the globe—despite never having ventured out of the Atlantic. Ultimately, he was revealed to be the victim of a storm in his own head. His family never saw him again after his boat blinked out of sight, and it would take them years to unravel what happened to him; even now, that’s a jagged-edged question they’ve each answered in their own way. The truth about the inventor’s phony voyage can only be guessed based on the evidence he left behind. What is certain is that when Crowhurst sailed from Teignmouth, he was tragically ill-prepared, but had staked so much on the journey that the circumstances carried him away like a riptide.

J ust as the Americans were shooting for the moon, the British had rediscovered the allure of the sea. In 1967, Francis Chichester electrified England by completing the first solo circumnavigation, with one stop in Australia, in his 16-metre yacht. The next obvious challenge was a non-stop solo sail. London’s Sunday Times announced a race in which competitors would set off any time between June 1 and Oct. 31 of 1968. There would be one prize—a Golden Globe trophy, giving the race its name—for the sailor who returned home first, and another prize of £5,000 for the fastest trip from departure date to return.

Crowhurst, inspired by his fascination with Chichester, immediately declared himself a competitor. “I think he felt a certain amount of jealousy—he wished it had been him, and he really thought he could do the next thing,” says Simon. His father had sailed the wildly varying tides and aggressive currents of the Bristol Channel, but he’d never attempted anything on the open ocean. Like Chichester, Crowhurst had served in the Royal Air Force, though he was kicked out because of some bit of mischief. He joined the British Army, where another disciplinary incident got him booted. He studied electronics engineering, raced cars and, after marrying Clare, started a small company, Electron Utilisation, to manufacture the Navicator, a sailing navigation device he designed to work on radio signals. Crowhurst would get so absorbed tinkering in his workshop behind the house that his children would have to go out and wave from the doorway so he’d come in and eat dinner.

Simon adored his father. He didn’t understand the grown-up jokes, but he knew his dad was funny because he was always making people laugh. Crowhurst read to his children in goofy voices and drew futuristic aircraft and spaceships for them. He loved building things: circuit boards, model boats, elaborate landscapes where Simon’s plastic dinosaurs could live. Simon would grow up to pursue a career in geology, tracing his lifelong interest back to those model volcanoes. One of his lingering memories is leaping over muddy creeks with his father on their way to Pot of Gold, the 20-foot sloop Donald sailed near their home in Bridgwater in southern England. Crowhurst also loved poetry, and Edward Lear’s “The Jumblies” was a favourite he’d recite from memory:

“They went to sea in a Sieve, they did, In a Sieve they went to sea: In spite of all their friends could say, On a winter’s morn, on a stormy day, In a Sieve they went to sea! And when the Sieve turned round and round, And every one cried, ‘You’ll all be drowned!’ They called aloud, ‘Our Sieve ain’t big, But we don’t care a button! We don’t care a fig! In a Sieve we’ll go to sea!'”

When he struggled with sales of the Navicator, Crowhurst convinced local businessman Stanley Best to back his company until things picked up. When they didn’t, Best wanted to pull out. Instead, Crowhurst persuaded him to bankroll his Golden Globe entry, touting it as an epic advertisement for his company and assuring his benefactor he could win both prizes. “It was, I suppose, the glamour of the idea, the publicity and the excitement–and the persuasiveness of Donald,” Best told the authors of The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst (published a year after the race, with detailed reconstructions based on Crowhurst’s logbooks). The pair struck an agreement that if the race went badly, or if Crowhurst withdrew, Electron Utilisation would buy back the boat—spelling certain bankruptcy. Best also re-mortgaged the Crowhurst family home to repay some of the business debts. Crowhurst would either return home in triumph, his meagre finances fattened by the prize money and his business saved by the publicity, or he would lose everything—even the home his children were living in.

He decided to race a trimaran, a new craft thought to move faster than single-hull yachts. But the speed had a cost: Trimarans were difficult to right if they capsized. Crowhurst designed a clever system of sensors, buoyancy bags and pumps to stabilize his boat, but by the time he departed, none of it had been tested or even installed properly. Instead, the boat-building process was so rushed that water leaked in through the hatches, the bailing pipe was somehow never put on board and screws fell from the mainmast like raindrops. Donald Crowhurst was going to sea in the Jumblies’ sieve.

B y the time he set off—on the last possible date of entry—eight competitors had left up to five months ahead of him. Among them were a Frenchman, Bernard Moitessier, who viewed the voyage as a spiritual quest; a naval officer named Nigel Tetley, also sailing a trimaran; and Robin Knox-Johnston, a young merchant navy officer sailing a tiny wooden scrap of a boat. The race route wound south through the Atlantic, around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean, south of Australia. It then crossed the Pacific and looped past South America’s Cape Horn before hitting the home stretch north through the Atlantic. Crowhurst had calculated that he could complete the race in as few as 130 days, faster than any of the others, and even make up enough time to return home first.

Harsh reality destroyed those expectations immediately. His boat was a heap of leaky lumber, the slowest in the race. “Racked by the growing awareness that I must soon decide whether or not I can go on,” he wrote in his logbook early on. “What a bloody awful decision–to chuck it in at this stage!” But in his calls and telegrams, Crowhurst never admitted how bad things were.

The race was a constant source of excitement and confusion for his children. Reporters showed up periodically, and the voyage was frequently the subject of chatter at school. Simon and his siblings told friends their father would be home when the daffodils returned in the spring, because that’s what Clare told them, and Simon talked about how his father would avoid the sharks that were sure to be out there, but whales didn’t usually smash into boats. At home, a world map was hung on the playroom wall, and each time the competitors radioed in their coordinates, Clare plotted their location on the map with pins. The other sailors were oceans ahead of her husband.

Crowhurst had hired former crime reporter Rodney Hallworth as a PR agent; he began sending him vague, chirpy cables, never specifying where he was, just where he was headed. He had apparently found a way to save face: He simply began inventing the voyage he wished for. Hallworth was oblivious, spinning those fuzzy updates with even more optimism for the press. Then Crowhurst sent a telegram claiming he’d covered 243 miles in one day—a solo sailing record. Overnight, he was transformed from faltering footnote to the lead news item. Crowhurst also started maintaining two sets of navigational coordinates: one accurate and the other a meticulously constructed fake journey. In January, he meandered around Rio de Janeiro while claiming to be close to rounding the Cape of Good Hope. It would soon become obvious his radio signals were off, so he cabled Hallworth saying he was having problems with his generator flooding and would send messages when possible. Then he disappeared into the wind for nearly three months.

Crowhurst’s family had adjusted to not hearing from him for long periods, but as the weeks stretched on, dread crept in. The map on the playroom wall grew more haunting by the day, the pin representing Crowhurst frozen implacably in place. “We hadn’t realized quite how serious the situation was because everyone had just gone quiet,” Simon recalls. “We were asking from time to time, and when you realized nothing had been heard, there’s a tacit assumption that you don’t talk about it anymore.” As Simon remembers it, the map was one day quietly removed from the wall; Clare still insists it stayed where it was.

By early April, the three other competitors remaining—the rest had been forced out by illness, accidents or boat problems—were in the home stretch. (When Moitessier, the eccentric Frenchman, passed Cape Horn, he couldn’t bring himself to return to civilization, so he sailed off around the globe again.) Knox-Johnston was in the lead, with Tetley hot on his heels. Finally, Crowhurst resurfaced. He sent Hallworth a telegram suggesting he was about to round Cape Horn—a major milestone, had it been true—and asking cheekily for a race update. “WHATS NEW OCEANBASHINGWISE,” Crowhurst inquired.

The full depth of Clare’s fear for her husband only became obvious to her children when it gave way to euphoric relief with the news of his telegram. They had a party in the garden, celebrating with ice cream, cookies and jellies. Simon knows it might not be an accurate recollection, but in his childhood memory, the sun was shining. “It was as if he’d come back from the dead and was just moving inexorably back home,” he recalls.

On board the Teignmouth Electron, even as Crowhurst turned north from the coast of Brazil and headed for home in earnest, things were not so bright. Throughout the journey, he had made audio recordings and composed bawdy limericks and romantic descriptions of life at sea, all of them showing off a charming and cheeky public persona. But now, Crowhurst’s writing revealed loneliness, depression and a retreat from reality. He scrawled mathematical formulas purported to represent universal life truths, along with rambling meditations on his childhood, his understanding of God and human dishonesty. He fixated on Einstein’s theory of relativity and argued furiously with the dead physicist in his notes. The loneliness appeared to be consuming Crowhurst, as did the strain of maintaining his deception.

Hallworth sent a cable urging his client on: “YOURE ONLY TWO WEEKS BEHIND TETLEY / PHOTO FINISH WILL MAKE GREAT NEWS.” On April 22, Knox-Johnston arrived home to great fanfare and claimed the Golden Globe trophy. But since his trip had been leisurely, England’s breathless attention shifted to Crowhurst and Tetley (who had departed six weeks earlier than Crowhurst) to see who would complete the fastest journey. In early May, Hallworth sent another galvanizing cable: “TEIGNMOUTH AGOG AT YOUR WONDERS / WHOLE TOWN PLANNING HUGE WELCOME.” In response, Crowhurst sent a telegram warning it was impossible for him to beat Tetley.

When he heard about Crowhurst materializing out of nowhere, Tetley pushed his badly damaged boat to the limit. Off Portugal, he battled too hard through a storm, and one of his three floats snapped off and slammed into the centre hull. Tetley scrambled into a life raft, then watched his boat sink beneath the waves—a near tragedy Crowhurst learned about in a cable from Clare. Now he was the only remaining sailor in the race.

A few weeks later, the power supply partially failed on Crowhurst’s radio transmitter, making it impossible for him to send messages. He spent his time obsessively trying to repair the device, desperate to speak to Clare. On June 22, Crowhurst got the transmitter functioning well enough that he could send Morse code messages, but he was still unable to make direct calls. He let his boat drift aimlessly through the mysterious Sargasso Sea, historically rumoured to swallow up ships in the thick carpet of seaweed on its surface. He began writing a rambling, 25,000-word meditation on free will, physics, perception, the nature of God and the possibility of freeing the soul from the body.

Another cable arrived from Hallworth, crowing that 100,000 people would welcome him back to Teignmouth. With just weeks until her husband’s expected return, Clare told a newspaper about the giddiness that had overtaken her family. “Now most of the bad things are lost in the tremendous anticipation of seeing him again,” she said. “It’s almost like the atmosphere you get when you have a child. We just can’t wipe the smiles off our faces.” A radio operator relayed a message to Crowhurst that his family was excited to meet him near the Scilly Isles before he reached the crowds. Crowhurst sent back word that they should not come, insisting the operator confirm receipt. Clare was hurt, but decided he must have wanted to spare them all seasickness.

Crowhurst’s writing grew more anguished and abstract. Finally, on the morning of July 1, he offered a long, elliptical confession of what he’d done, then concluded with:

“It is finished It is finished IT IS THE MERCY.”

Nine days later, a Royal Mail ship discovered the Teignmouth Electron adrift in the Atlantic. The logbooks and notes that contained all the evidence of Crowhurst’s forgery, along with the fraying of his mind, were sitting in the cabin. Crowhurst was gone.

A s Simon remembers it, two stone-faced nuns appeared in the family’s driveway that evening and asked to speak to Clare. Later, Clare took the children upstairs to Roger’s room, sat them down on the bed and told them their father’s boat had been found, but he wasn’t on it. Then she began to cry. Confused and desperate to comfort their mother, the children reassured Clare that surely their father would be found. “One moment you’re expecting him to come back, and the next the boat’s found and he’s not on it,” Simon recalls. “It just knocked everyone flat.”

The Sunday Times started a relief fund for the family, and Knox-Johnston donated his £5,000 prize. Simon and his family still believed so strongly in Crowhurst’s resourcefulness that they held out hope he might have climbed aboard a lifeboat or some other craft. They didn’t yet know what his notes revealed about his journey and state of mind. The captain of the mail ship had turned the logbooks over to Hallworth, who in turn passed them on to the Sunday Times. The paper had won the auction for exclusive rights to what was still thought to be Crowhurst’s heroic around-the-world story. Once they understood the reality of Crowhurst’s voyage, the Times editors decided they had to run with the story, but first, they showed it to Clare.

The sad, bizarre tale took over the front pages of all the English papers. But it would be years before Simon understood what the logbooks revealed and how the rest of the world saw this would-be hero he knew so intimately. “I did feel always as if I’d just stepped off a ship and [was] trying to find [my] land legs again,” Simon says. “The very things you took for granted were not quite solid, and you needed to reappraise things.” When he was about 16, he read Strange Voyage. Simon could recognize his father in the logbooks, especially in the early stages, before Crowhurst started to slip away from himself. But the creeping distress in his words made Simon feel as though he were reading a letter from his father distorted by someone else. “They are harrowing reading and a kind of psychological and intellectual vortex,” he says. “In some ways, you have to be careful not to get drawn in.”

In all the uproar and speculation over the years, what bothered Simon most were claims that his father was trying to cheat his way to victory. “He was trying to avoid appearing to have humiliatingly failed—because actually he had humiliatingly failed,” Simon says. “He didn’t want that to be apparent because the financial consequences for his business and his family would have been so terrible.” Simon thinks that, for quite a long time into the race, his father kept open the possibility of giving everything up, confessing where he’d been and brushing off the rest as an elaborate prank. He points to a blank section in the accurate logbook, believing his father intended to eventually fill it in and reveal the truth. “I don’t think at first it was a grand scheme,” Simon says. He believes his father conjured up false reports like that record day of sailing so he could put in the appearance of a strong performance and then drop out of the race with some dignity. But as his lies propelled the Teignmouth Electron ever further from its true location, Crowhurst was trapped: It would be impossible to dismiss the whole thing as a lark without serious humiliation.

Simon thinks his father finally broke his radio silence at a time when he figured several competitors would have already completed the race. Instead, no one was home yet, and he found himself thrust back into the spotlight because he appeared to have a good shot at finishing fastest. He deliberately slowed down, which Simon views as an effort to take pressure off Tetley. When Tetley nearly died, Simon believes the circumstances just closed in. “When Nigel Tetley’s boat sank, obviously there was no way he could claim it was a joke,” he says quietly. He is careful in conveying his own interpretation of how his father died because he doesn’t want to upset his family members, who have each reached their own painful conclusions. (Clare, for one, has always maintained Crowhurst would not have taken his own life, but may have accidentally fallen overboard.) All Simon will say is that when someone who is mentally ill dies, he thinks it’s really the illness that’s killed them.

Crowhurst’s story has inspired countless TV shows, news stories, documentaries and feature films along with several plays and an opera. Simon understands why the dark voyage is such an irresistible tale, even if it’s an incomplete portrait of the father he loved. “When something dramatic like this happens, people tend to think this summarizes the entire person,” he says. “It’s one part of his life and how his life ended, but it wasn’t all there was to say about him. It’s a pity that people remember him for the thing that went most disastrously wrong, but that’s how it’ll always be. I suppose he’s remembered at least, so that’s maybe something.”

The Teignmouth Electron changed hands several times after it was rescued from the Atlantic, and it now rests on a tiny lick of the Cayman Islands, disintegrating languorously in the Caribbean sun. Simon has a black-and-white photograph of it, sent to him by the British artist Tacita Dean, which hangs at the top of the stairs in his house. He loves the photo because it’s taken from the air and at a distance, with the sea twinkling beyond the prow and the boat looking more complete than it ever really was. He hasn’t seen it in person since his father kissed him goodbye that October afternoon, and he has no great desire to. For Simon, the real Teignmouth Electron is the boat that never existed–the technological marvel his father dreamed he could sail around the world. “That boat never came into being,” Simon says. “And that would be the boat I’d really like to see.”

This story was originally published in 2016.

Corey Arnold; Eric Tall/Getty Images; geographyphotos/Alamy

Bernhard Langer's secret to staying young — and winning majors

Today would've been Masters Sunday, and while we can't watch the final round at Augusta, we can still ask the important questions. Like, how does two-time Masters champ Bernhard Langer keep himself in the competitive mix at 62? Turns out it's cake. Mostly, cake.

How Canada's Mike Soroka grew into one of baseball's best young arms

Inside the mentorship with a former big-leaguer that set Atlanta Braves hurler Mike Soroka on track to be one of the best-ever Canadian pitchers.

The 1919 Stanley Cup Final and modern-history's deadliest pandemic

Cut short after the death of Canadiens defenceman, Joe Hall, the 1919 Stanley Cup Final offers a window into the ravages of and reaction to the Spanish Influenza.

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright and DMCA Notice

Donald Crowhurst and his Fatal Race Round the World

In 1968, British newspaper The Sunday Times sponsored the first ever round-the-world yacht race. Guaranteed excellent publicity from the paper, nine contestants enlisted, drawn by the glamor of winning such a race, as well as the £5,000 prize for the fastest time (as much as $120,000 today).

The race was well organized but there were several safety concerns. Yachts were to be manned by a single person only as the race was a solo one, and the race would be non-stop. Competitors could not be vetted thoroughly on the safety of their boats and their abilities as sailors , and there were no entry requirements.

Competitors could start the race at any point between 1 June and 31 October 1968. One such competitor, who set off on the very last day, was Donald Crowhurst.

An Ambitious Man

Donald Crowhurst was not a professional sailor but had some knowledge and experience about sailing. He was an inventor and electronics engineer, and hoped to use this to his advantage during the race.

To aid in his navigation, he created a radio-direction finder that he named “Navicator” and he would make the attempt in a very unusual boat design, a trimaran called the Teignmouth Electron . Trimarans could theoretically travel much faster than monohull boats, but had not been tested on such a grueling expedition.

Crowhurst hoped to stabilize his business with the publicity and money that he would get by winning this race, but the upfront costs were steep. To take part, he raised financing from some businessmen and mortgaged his home as well.

This allowed him to finish work on the Teignmouth Electron which he had constructed specially for the voyage. The boat-builder promised Crowhurst that the boat would be speedy but warned about stability issues in heavy seas.

But on the first sea trial of the boat, a few noticeable problems came up. The deadline was rapidly approaching and it wasn’t possible for Crowhurst to equip new parts and repair the vessel properly to make it ready for the race.

- The Sarah Joe Mystery: Disappearance in the Pacific

- SS Baychimo: Ghost Ship of the Arctic

He only had two ways and was faced with a dire choice: either sail and take part in the race with a doubtful boat, or give up to face bankruptcy and humiliation. Crowhurst, fatefully, took the first option, setting sail in a boat untested in either design or practice.

The Race Begins!

Just like the boat wasn’t ready, the weather wasn’t favorable for the race as well. Clare, Crowhurst’s wife, suggested to him not to take part in it, as there was a great risk. But as she saw Crowhurst sobbing with the thought of humiliation, she and their four kids tried to make Crowhurst believe he could do anything. They didn’t want him to regret the thought of giving up.

On 31st October 1968, the weather miraculously calmed and gave Crowhurst his opportunity to start the voyage. Crowhurst kissed the forehead of each of his children and asked the elder ones to take care of their mother, and launched the Teignmouth Electron .

Soon after the race began, Crowhurst observed that the boat was already leaking like a sieve. And he realized right at that moment that this boat wouldn’t be able to take the blow from 30 or 40-foot (9 – 12 m) waves in the Southern Ocean , writing in the logs that the ship would probably sink once it entered heavy seas.

Trapped and with no options left, Crowhurst started to come up with a plan! He didn’t want to give up and live with humiliation forever, he would rather cheat than lose.

The Crooked Plan of Donald Crowhurst

GPS didn’t exist back then, and so the only way of checking the position of the boats after the race was through a review of the logbooks and the charts carried on each boat. Donald Crowhurst intended to use this to his advantage, saving his boat and completing the race.

Therefore, he started sending radio messages to the organizers giving false positions. He charted a false course down into the south Atlantic, and then, fearing his transmissions might give him away, he then disconnected the radio contact completely off the coast of Brazil .

Even these waters were too much for the T eignmouth Electron . His boat was so damaged at one point that he had to stop at a fishing port in Argentina to make some necessary repairs.

Crowhurst’s plan was to maintain two logbooks, one for his real journey and one for his fictitious race experience. The pressure of keeping two logbooks would have been extreme, and was made worse when he realized that his fictitious log wouldn’t be justifiable at close scrutiny if he won the race.

- Taken by the Ice: What Became of the Franklin Expedition Crew?

- Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight – Mystery at Sea