Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

1979 Fastnet Race: The race that changed everything

- Nic Compton

- May 18, 2022

Nic Compton investigates how the UK’s worst sailing disaster - the 1979 Fastnet Race - changed the way yachts are designed

The Royal Navy airlifted 74 survivors during three days of rescues. Credit: Getty

‘A soul-chilling surge of fear swept through all of us as we heard the terrifying sound of a breaking wave 40ft above us. In a few seconds the 10ft-high foaming crest was bearing down on us from behind like an avalanche. […] We braced ourselves for the pooping of our lives, but a split second before the onslaught from astern, the bow disappeared as we nosedived into a wall of water in front. […] As the bow submarined into this secondary wave, Grimalkin ’s stern rose until it arced over the bow and stood us on our nose. As we approached the vertical, crew were thrown against the back of the coachroof or out of the boat altogether. A split second later and we were hit from astern by the breaking wave and we pitchpoled.’

This is one of the defining moments of the 1979 Fastnet Race when, after having been knocked down multiple times and rolled through 360°, the 30ft Grimalkin was hit by a rogue wave and pitchpoled.

As she went through the roll, her rig collapsed and she remerged with a broken mast and the spars smashing against her topsides.

By then, the boat’s owner, David Sheahan, was dead, floating face down in the sea to windward, and two of the crew were slumped in the cockpit, also apparently dead.

Rescue helicopters went back in the days after the disaster to check every boat for survivors, including Grimalkin . Credit: Getty

Faced with this carnage, the remaining three crew – including the owner’s son, Matt Sheahan, then only 17, who wrote the passage above – decided to abandon ship and boarded the liferaft .

Only later did they discover that at least one of the crew left on board was still alive – Nick Ward, who went on to tell his tale in his book Left for Dead .

But of course Grimalkin wasn’t the only yacht to have succumbed to the Force 10 winds that ravaged the fleet that year.

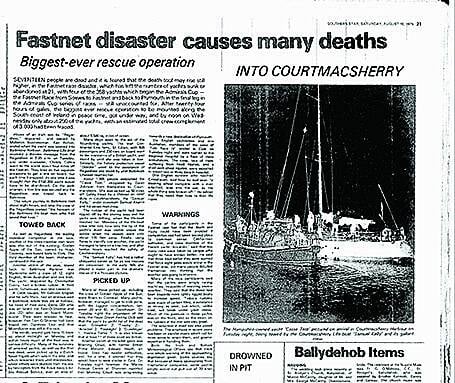

By the end of the 1979 Fastnet race, 24 boats had been abandoned, five boats had sunk, 136 sailors had been rescued, and 15 sailors killed.

It was and still is the deadliest yacht race in history – well ahead of the 1998 Sydney to Hobart race which left six people dead.

The rescue was described as the biggest peacetime life-saving operation in British history, and its impact has reverberated throughout the yachting world.

Stowage arrangements on yachts was one of the changes following the 1979 Fastnet Race, after many crews found it too dangerous to be below deck due to insecure equipment

It was a wake-up call for the emergency services and triggered a huge push for improved safety equipment.

But how much did it affect the course of boat design , and have the lessons of this deadliest of races really been learned, or is there a danger it could happen all over again?

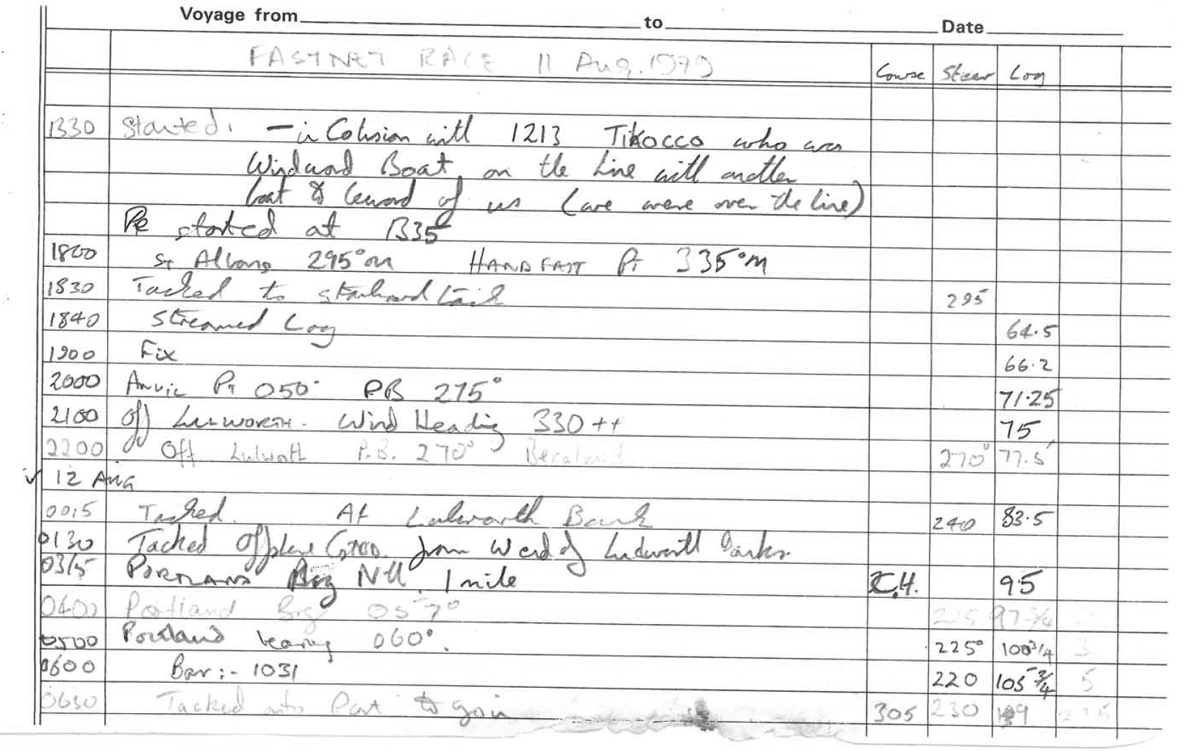

When the 303 boats gathered for the Fastnet Race on 11 August 1979, racing was still governed by the International Offshore Rule (IOR), first introduced in 1969.

After 10 years of experimentation, designers had found ways of maximising the rule, not always with desirable results.

‘In 1979 all boat racing was done under IOR, but it was already in decline, mainly because designers had found their weaselly way into the rule,’ says the former Royal Ocean Racing Club (RORC) technical director Mike Urwin, ‘which meant that unless you had the latest and greatest you didn’t stand a chance. The IOR produced boats which wholly optimised the rule but which were opposed to the rules of nature, such as hydrodynamics.’

One of the main complaints about the IOR was that it produced boats which were ‘short on stability’, as Urwin puts it.

The 1979 Fastnet Race Inquiry looked at weather reporting, safety gear, crew experience and tactics, and search and rescue procedures.

The rule contained a Centre of Gravity Factor, which encouraged designers to aim for the minimum stability allowed, bringing ballast inside the boat and even fitting wooden shoes on the bottom of keels to reduce weight.

The result was lightweight boats with wide beams, pinched ends and high freeboards, which in extreme weather had a tendency to roll over and stay over.

Another major failing of the rule was that, as it wasn’t possible to physically weigh them yet, the boats were weighed theoretically by measuring their shape at a series of stations and calculating the overall shape accordingly.

This lead to designers adding all kinds of strange appendages between the stations to increase the waterline length, which in turn meant the hulls became distorted and difficult to steer.

It was an altogether bad state of affairs yet, speaking 40 years after the 1979 Fastnet Race, designer Ron Holland – responsible for dozens of IOR racers, including Grimalkin – defends his and his colleagues’ approach.

‘We were designing boats to the IOR rule, so it wasn’t just boat design, it was trick design. Without those restrictions we would have designed boats that were less distorted and faster, but they wouldn’t have won races under the IOR rules. The racing rule forced us to design narrow sterns, so the boats were tricky to sail downwind: you had to be skilled to stay on your feet – it was all part of the game. We just took the handicap system as it was and designed boats as fast as possible around that – still bearing in mind that if you don’t finish you can’t win and you need structural integrity to keep sailing.’

Lessons from the wreckage of the 1979 Fastnet Race

Holland experienced the storm first hand, first from the deck of Golden Apple of the Sun and then, when the boat’s rudder broke off the Isles of Scilly , from the inside of a rescue helicopter.

‘I personally felt bad afterwards, especially because of those people who died. We had never had that before. But the weather was so extreme; the waves were of a size, shape and frequency that I’ve never seen before. I’m convinced that even a Colin Archer would have rolled over in those conditions.’

As the crews licked their wounds and the families mourned their dead in the aftermath of the 1970 Fastnet race, the RYA and the RORC commissioned an inquiry to find out what had gone wrong.

Three questionnaires were sent to the skipper and crews of all 303 yachts, and 669 completed questionnaires were fed into a computer for analysis.

Yacht designer Ron Holland took part on the 1979 Fastnet. He said the waves were of a size and frequency he had never seen before. Credit: Getty

The result was a 74-page report, which looked at everything from weather reporting to marine safety gear , crew experience and tactics, and search and rescue procedures.

Yet, despite recognising that many people felt designers had ‘gone to extremes which surpass the bounds of common sense’ in their quest for speed, the section on boat design is relatively short: less than three pages out of a 74-page report.

Indeed, the authors seem to go along with the ‘consensus of opinion’ that it was ‘the severity of the conditions rather than any defect in the design of the boats’, which was the main cause of the problem – all the while noting that 48% of the fleet had been knocked to horizontal, 33% had gone beyond horizontal, and five boats had spent between 30 seconds and six minutes fully inverted.

The report didn’t bother investigating knockdowns to horizontal (so-called B1 knockdowns) because it considered that these ‘have always been a potential danger in cruising and offshore racing yachts in heavy seas’, so they regarded them as normal.

New measures

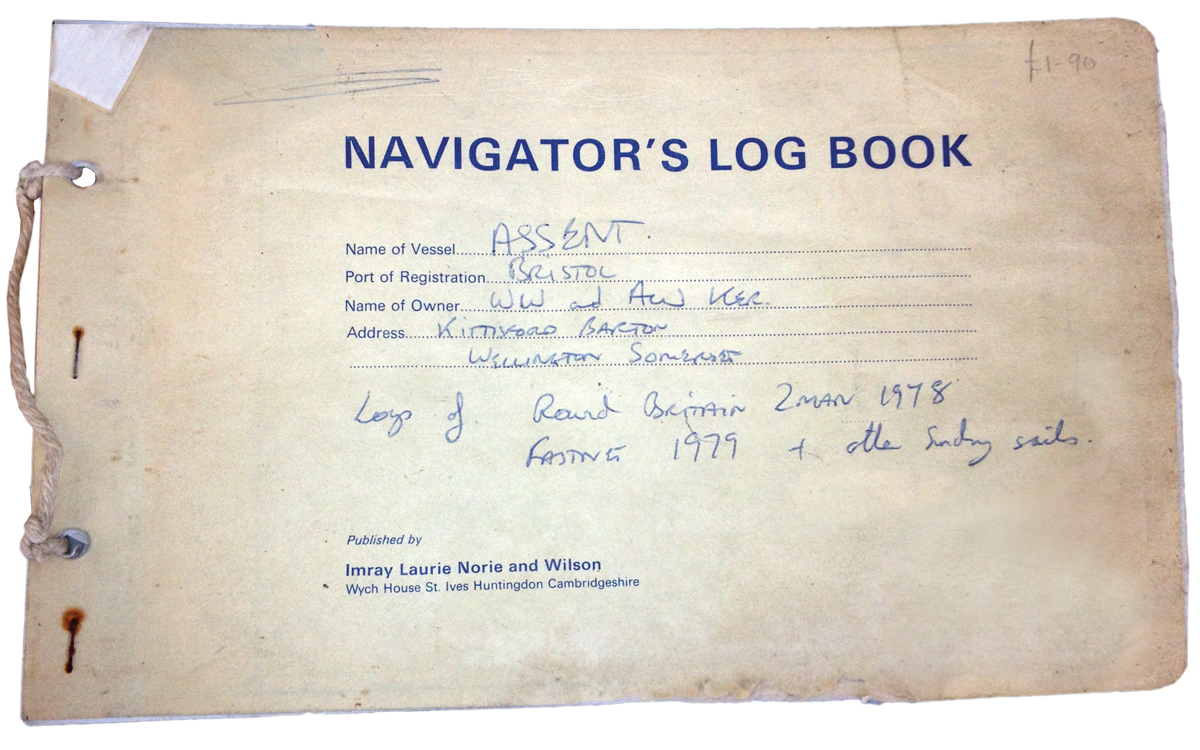

Buried in the appendices was a technical report comparing the stability of a Contessa 32 Assent – the only boat in the smallest class to complete the course – and a ‘1976 Half Tonner’ (generally assumed to be Grimalkin ).

The report showed the Contessa had a range of stability of 156° compared to just 117° for the Half Tonner, making the latter far more likely to stay inverted.

Despite these concerns, the report made few recommendations for changes in yacht design, apart from suggesting the RORC should consider changing its measurement rules and make it possible to exclude boats ‘whose design parameters may indicate a lack of stability’.

The overwhelming weight of the report, however, was about the weather, improving safety gear on boats and better procedures for search and rescue.

It concluded: ‘In the 1979 race the sea showed that it can be a deadly enemy and that those who go to sea for pleasure must do so in the full knowledge that they may encounter dangers of the highest order. However, provided that the lessons so harshly taught in this race are well learnt we feel that yachts should continue to race over the Fastnet course.’

Changes brought in after 1979 means boats have to meet the ISO 12217-2 stability standard in order to sail in the Fastnet Race. Credit: Carlo Borlenghi

Yet, despite this, racing rules did change.

From 1983, the Channel Handicap System (CHS) was introduced, initially alongside IOR and eventually, as the renamed International Rating Certificate (IRC), supplanting it.

The new rule encouraged a low centre of gravity by not penalising ballast in the keel.

Also, thanks to advances in technology, it was now possible to weigh boats which, according to Mike Urwin, ‘at a stroke’ stopped designers distorting the hull to get better rating – gone were the unseemly bumps and creases of IOR boats – and resulted in ‘more wholesome boats which were easier to handle’.

There were other changes.

From 1988, the CHS introduced a Safety & Stability Screening (SSS) system, which measured a boat’s stability and took into account factors such as rig, keel , and engine type.

Thus an inboard engine scored more highly than an outboard, and a sturdy, simple rig was favoured over the complex spiders webs of many IOR boats.

Features such as furling headsails, in-mast reefing and radar can have a big impact on a yacht’s stability. Credit: David Harding

Trisails and VHF radios became mandatory.

In due course, competitors were required to complete shorter, qualifying races before they were allowed to race in the Fastnet, and a certain percentage of the crew were expected to have a sea survival certificate.

And Urwin points to another way the 1979 Fastnet Race has improved boat safety.

When it came to devising an ISO standard for yacht construction in the UK in the 1990s, the starting point for stability was the SSS system produced by the RORC.

Continues below…

Heavy weather sailing: preparing for extreme conditions

Alastair Buchan and other expert ocean cruisers explain how best to prepare when you’ve been ‘caught out’ and end up…

Adventure: guide to sailing in storms

Award-winning sailor and expedition leader Bob Shepton regularly sails some of the most storm-swept latitudes in the world. Not bad…

How keel type affects performance

James Jermain looks at the main keel types, their typical performance and the pros and cons of each

The resulting ISO 12217-2 (which Urwin calls a ‘gold standard for stability’) is now not only used to qualify for RORC offshore races such as the Fastnet, but is used by most British designers to pass the EU’s Recreational Craft Directive rules.

Even more significantly, perhaps, the tragedy prompted a change of attitude, according to former ROCR race director Janet Grosvenor.

‘The 1979 Fastnet was the trigger that started a greater awareness of safety issues in sailing that exists today,’ she says.

‘You can see it in people’s ordinary lives and their perception of safety. Young people nowadays turn up with their own lifejacket , which they know fits them and is up to date, whereas before they used to all be provided by the boat. It’s a mindset. We are living in a more health and safety conscious world these days.’

The new approach came to the fore in 2007 when, for the first time in its 82-year history, the start of the race was delayed after the Met Office warned of extreme conditions in the Irish Sea, similar to 1979.

In her role as race director, Grosvenor delayed the start by 25 hours, ensuring the bulk of the fleet was still in the English Channel when the storm hit and could retire safely if necessary.

And retire they did, with 207 of the 271-strong fleet taking shelter in ports along the south coast.

For Grosvenor, the fact that no boats capsized and no lives were lost was a vindication of this new attitude.

Lasting legacy of the 1979 Fastnet Race

Matt Sheahan’s experiences during the 1979 Fastnet Race affected him for the rest of his life and sparked a personal crusade.

After studying Yacht Design at Southampton University, he worked at Proctor Masts before eventually joining Yachting World as racing editor.

In his guise as chief boat tester, he conducted a campaign to make yacht manufacturers more open about stability.

‘I was determined to include stability information with all our boat tests. I wasn’t trying to change the world or say there should be set limits, it was just about getting people to understand the issue and know what their boat is suitable for. When you sail an Ultra 30, with eight crew and minimal ballast, you know if you get it wrong you’ll be swimming and the boat will probably capsize. That’s ok, it’s a calculated risk taken by experienced sailors. What’s not acceptable is when you have a cruising family who don’t have much experience and just want a boat for weekend cruising, and you sell them a boat which is capable of capsizing if it heels beyond 100° or 105° – which is the case with many boats by the time you put all the extra bits of kit on the mast. But people aren’t aware.’

The Contessa 32, Assent , pictured taking part in Cowes Week, was the smallest boat to complete the 1979 Fastnet Race

As ever, suitability of a boat for a specific use is key.

It is important that buyers understand what a boat is suitable for and what it is not. So, are boats safer now than they were in 1979?

There’s little doubt that the advances in safety equipment, clothing and building materials have improved sailors’ chances of survival in extreme weather conditions.

And there are signs that designers are producing more seaworthy designs than before.

Conditions in the 1998 Sydney to Hobart Race were said to be at least as bad as in the 1979 Fastnet Race, yet only 18% of the 115 boats in the race had B1 knockdowns and only 3% had B2 knockdowns – compared to 48% and 33% in the Fastnet.

Heed the warnings

But Sheahan is cautious: ‘What worries me is that the lessons from the 1979 Fastnet get forgotten. Most yachts have better stability characteristics now, partly because of regulations but also because they are generally getting bigger, so they have more form stability anyway. But by the time you add in mast-furling , furling staysails, and all the other bits of kit on the mast, the centre of gravity starts to creep up and you have a problem again. There’s a trend to make cruising boats look like fancy hotel foyers down below, to make them more appealing to the family. But the minute the boat heels over, it’s a nightmare to get across. With nothing to hold onto, someone’s going to get hurt. There’s also a move towards fine bows and over-wide sterns, making boats harder to steer downwind. So stability might be better, but the handling is getting worse.’

Urwin also thinks we are far from immune from a repeat of 1979.

The subsequent inquiry into the 1979 Fastnet Race recommended that blocking arrangements on main companionways should be totally secure

‘With the best will in the world we can’t forecast exactly what weather is going to do. If it happens again, modern boats are less likely to get into trouble, and if they do get into trouble the safety equipment is much better. We have by various means, some directly related to the 1979 Fastnet, improved the design of boats so they are more seaworthy. But never say never. With climate change creating extreme weather, it could happen again.’

The truth is that boat design is always going to be a compromise between speed and safety and that no boat is guaranteed to survive all weather conditions.

And one thing that becomes clear from all the first-hand accounts of the 1979 Fastnet Race is that the conditions were beyond anything competitors had encountered before.

Today’s sailors would do well not to assume that modern boats could survive any better than those flawed boats of 40 years ago.

As Ron Holland puts it: ‘If a fleet of boats racing on the Solent was hit by that Fastnet storm, they would still find it difficult to steer and the result wouldn’t be that different. I’ve done a lot of miles at sea but I’ve never seen conditions like that.’

Sailors take heed.

Stability research after the 1979 Fastnet Race

The Contessa 32 was used in the research into the causes of knockdowns after the 1979 race Credit: Graham Snook/Yachting Monthly

The Fastnet disaster prompted the Wolfson Unit at Southampton University to undertake detailed research into the causes of B1 (90°) and B2 (full inversion) knockdowns.

Its conclusions were striking.

- yacht with a stability range of 150° or more, like a Contessa 32 (pictured), will not remain inverted after capsize, as the wave motion alone is enough to bring it back up.

- If the wave height is 60% or more than the length of the boat, then capsize is almost inevitable, therefore, smaller yachts are more liable to be capsized than bigger ones.

- The Wolfson Unit also found that a yacht which has a stability range of 127° when fitted with conventional sails drops to an alarming 96° when fitted with in-mast mainsail and roller-furling genoa.

Yacht construction

The 1979 Fastnet Inquiry also highlighted several ‘weaknesses’ in relation to yacht construction.

Steering gear

Many rudders failed during the race due to the weakness of the carbon fibre used in the construction.

The report authors highlighted that although emergency steering would only give ‘minimum directional control’ it was important it would work to get a yacht safely to harbour.

Watertight Integrity

The design and construction of main companionways was ‘the most serious defect’ affecting watertight integrity.

The inquiry recommended that blocking arrangements should be totally secure but openable from above and below decks.

Bilge pumps should also discharge overboard and not into the cockpit, unless the cockpit is open-ended.

Many of the crews found it too dangerous below decks as their yachts rolled due to insecure equipment, like batteries, becoming flying ‘missiles’.

The stowage arrangements in some boats were designed to be effective only up to 90° angle of heel.

Deck Arrangements

The inquiry found cockpit drainage arrangement in some of the boats was ‘inadequate’, and called for a requirement for cockpits to drain within a minimum time.

The report also highlighted the problems with yachts under tow, and recommended a requirement for a strong securing point on the foredeck and a bow fairlead for anchor cable and towing warp.

The report also called for adequate toe-rails to be fitted, especially forward of the mast.

Enjoyed reading 1979 Fastnet Race: The race that changed everything?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price .

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals .

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram.

Racing the Storm: The Story of the Mobile Bay Sailing Disaster

When hurricane-force winds suddenly struck the Bay, they swept more than 100 boaters into one of the worst sailing disasters in modern American history

Matthew Teague, Photographs by Brian Schutmaat, Illustrations by Michael Byers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/d7/8fd7f047-a084-4e32-a01b-a9ceec77b452/julaug2017_a07_disasteratsea.jpg)

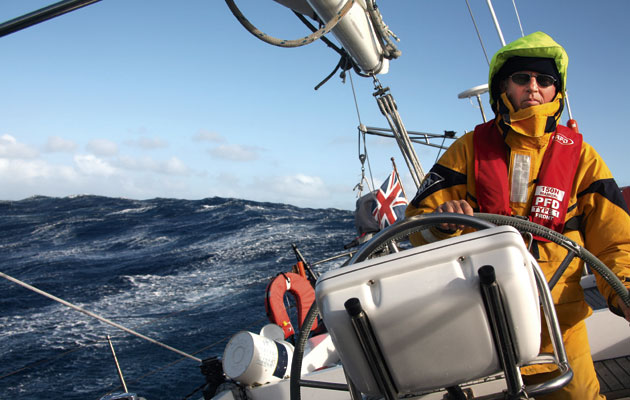

The morning of April 25, 2015, arrived with only a whisper of wind. Sailboats traced gentle circles on Alabama’s Mobile Bay, preparing for a race south to the coast.

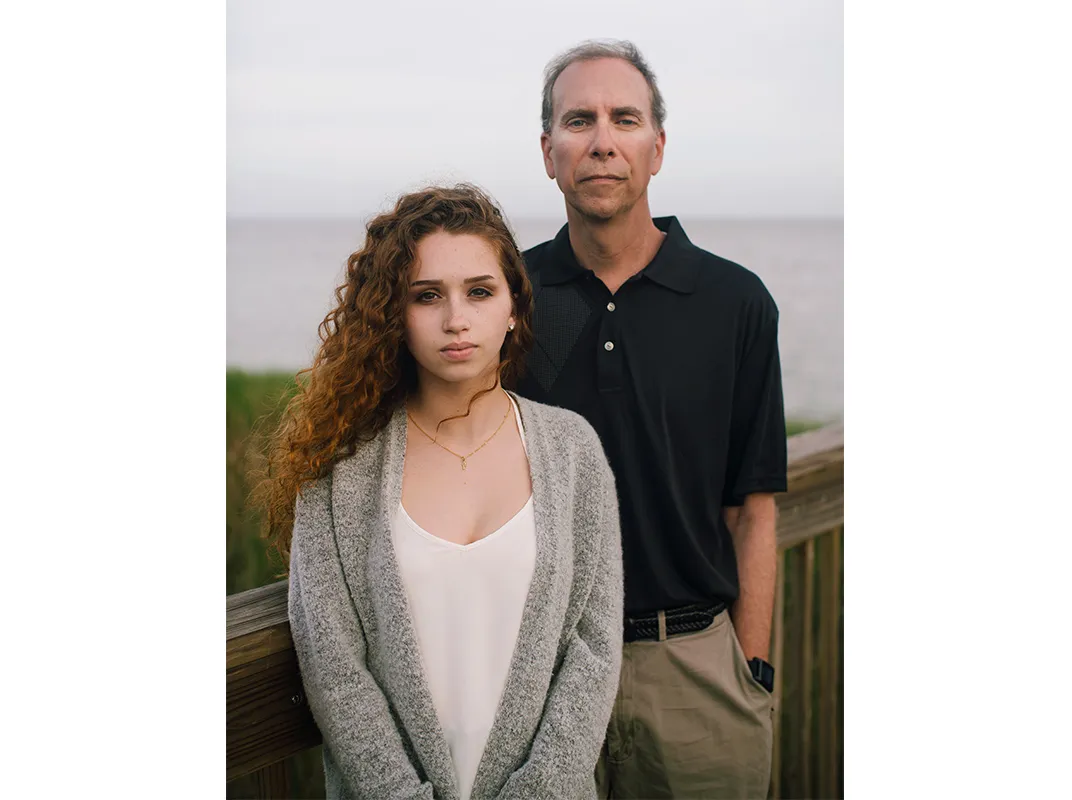

On board the Kyla , a lightweight 16-foot catamaran, Ron Gaston and Hana Blalack practiced trapezing. He tethered his hip harness to the boat, then leaned back over the water as the boat tilted and the hull under their feet went airborne.

“Physics,” he said, grinning.

They made an unusual crew. He was tall and lanky, 50 years old, with thinning hair and decades of sailing experience. She was 15, tiny and pale and redheaded, and had never stepped on a sailboat. But Hana trusted Ron, who was like a father to her. And Ron’s daughter, Sarah, was like a sister.The Dauphin Island Regatta first took place more than half a century ago and hasn’t changed much since. One day each spring, sailors gather in central Mobile Bay and sprint 18 nautical miles south to the island, near the mouth of the bay in the Gulf of Mexico. There were other boats like Ron’s, Hobie Cats that could be pulled by hand onto a beach. There were also sleek, purpose-built race boats with oversized masts—the nautical equivalent of turbocharged engines—and great oceangoing vessels with plush cabins belowdecks. Their captains were just as varied in skill and experience.

A ripple of discontent moved through the crews as the boats circled, waiting. The day before, the National Weather Service had issued a warning: “A few strong to severe storms possible on Saturday. Main Threat: Damaging wind.”

Now, at 7:44 a.m., as sailors began to gather on the bay for a 9:30 start, the yacht club’s website posted a message about the race in red script:

“Canceled due to inclement weather.” A few minutes later, at 7:57 a.m., the NWS in Mobile sent out a message on Twitter:

Don't let your guard down today - more storms possible across the area later this afternoon! #mobwx #alwx #mswx #flwx — NWS Mobile (@NWSMobile) April 25, 2015

But at 8:10 a.m., strangely, the yacht club removed the cancellation notice, and insisted the regatta was on.

All told, 125 boats with 475 sailors and guests had signed up for the regatta, with such a variety of vessels that they were divided into several categories. The designations are meant to cancel out advantages based on size and design, with faster boats handicapped by owing race time to slower ones. The master list of boats and their handicapped rankings is called the “scratch sheet.”

Gary Garner, then commodore of the Fairhope Yacht Club, which was hosting the regatta that year, said the cancellation was an error, the result of a garbled message. When an official on the water called into the club’s office and said, “Post the scratch sheet,” Garner said in an interview with Smithsonian , the person who took the call heard, “Scratch the race” and posted the cancellation notice. Immediately the Fairhope Yacht Club received calls from other clubs around the bay: “Is the race canceled?”

“‘No, no, no, no,’” Garner said the Fairhope organizers answered. “‘The race is not canceled.’”

The confusion delayed the start by an hour.

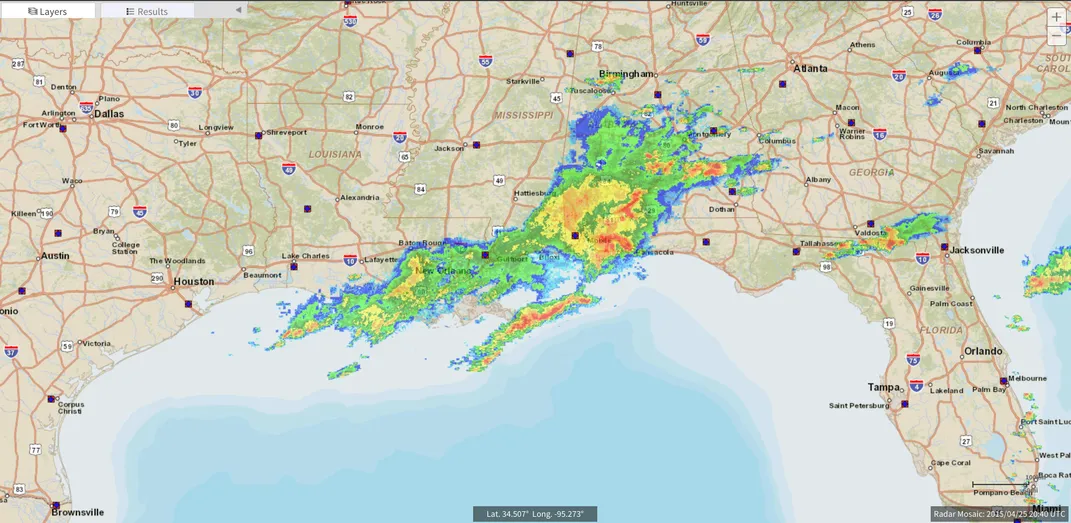

A false start cost another half-hour, and the boats were still circling at 10:45 a.m. when the NWS issued a more dire prediction for Mobile Bay: “Thunderstorms will move in from the west this afternoon and across the marine area. Some of the thunderstorms may be strong or severe with gusty winds and large hail the primary threat.”

Garner said later, “We all knew it was a storm. It’s no big deal for us to see a weather report that says scattered thunderstorms, or even scattered severe thunderstorms. If you want to go race sailboats, and race long-distance, you’re going to get into storms.”

The biggest, most expensive boats had glass cockpits stocked with onboard technology that promised a glimpse into the meteorological future, and some made use of specialized fee-based services like Commanders’ Weather, which provides custom, pinpoint forecasts; even the smallest boats carried smartphones. Out on the water, participants clustered around their various screens and devices, calculating and plotting. People on the Gulf Coast live with hurricanes, and know to look for the telltale rotation on weather radar. April is not hurricane season, of course, and this storm, with deceptive straight-line winds, didn’t take that shape.

Only eight boats withdrew.

On board the Razr , a 24-foot boat, 17-year-old Lennard Luiten, his father and three friends scrutinized incoming weather reports in granular detail: The storm appeared likely to arrive at 4:15 p.m., they decided, which should give them time to run down to Dauphin Island, cross the finish line, spin around, and return to home port before the front arrived.

Just before a regatta starts, a designated boat carrying race officials deploys flag signals and horn blasts to count down the minutes. Sailors test the wind and jockey for position, trying to time their arrival at the starting line to the final signal, so they can carry on at speed.

Lennard felt thrilled as the moment approached. He and his father, Robert, had bought the Razr as a half-sunk lost cause, and spent a year rebuilding it. Now the five crew members smiled at each other. For the first time, they agreed, they had the boat “tuned” just right. They timed their start with precision—no hesitation at the line—then led the field for the first half-hour.

The small catamarans were among the fastest boats, though, and the Kyla hurtled Hana and Ron forward. On the open water Hana felt herself relax. “Everything slowed down,” she said. She and Ron passed a 36-foot monohull sailboat called the Wind Nuts , captained by Ron’s lifelong friend Scott Godbold. “Hey!” Ron called out, waving.

Godbold, a market specialist with an Alabama utility company whose grandfather taught him to sail in 1972, wasn’t racing, but he and his wife, Hope, had come to watch their son Matthew race and to help out if anyone had trouble. He waved back.

Not so long ago, before weather radar and satellite navigation receivers and onboard computers and racing apps, sailors had little choice but to be cautious. As James Delgado, a maritime historian and former scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, puts it, they gave nature a wider berth. While new information technology generally enhances safety, it can, paradoxically, bring problems of its own, especially when its dazzling precision encourages boaters to think they can evade danger with minutes to spare. Today, Delgado says, “sometimes we tickle the dragon’s tail.” And the dragon may be stirring, since many scientists warn that climate change is likely to increase the number of extraordinary storms.

Within a few hours of the start of the 2015 Dauphin Island Regatta, as boats were still streaking for the finish line, the storm front reached the port of Pascagoula, Mississippi, 40 miles southwest of Mobile. It slammed into the side of the Manama , a 600-foot oil tanker weighing almost 57,000 tons, and heaved it aground.

Mobile Bay, about 30 miles long and half as wide, is fed from the north by five rivers, so that depending on the tide and inland rains, the bay smells some days of sea salt, and others of river silt. A deep shipping channel runs up its center, but much of the bay is so shallow an adult could stand on its muddy bottom. On the northwestern shore stands the city of Mobile, dotted with shining high-rises. South of the city is a working waterfront—shipyards, docks. Across the bay, on the eastern side, a high bluff features a string of picturesque towns: Daphne, Fairhope, Point Clear. To the south, the mouth of the bay is guarded by Dauphin Island and Fort Morgan peninsula. Between them a gap of just three miles of open water leads into the vast Gulf of Mexico.

During the first half of the race, Hana and Ron chased his brother, Shane Gaston, who sailed on an identical catamaran. Halfway through the race he made a bold move. Instead of sailing straight toward Dauphin Island—the shortest route—he tacked due west to the shore, where the water was smoother and better protected, and then turned south.

It worked. “We’re smoking!” he told Hana.

Conditions were ideal at that point, about noon, with high winds but smooth water. About 2 p.m., as they arrived at the finish line, the teenager looked back and laughed. Ron’s brother was a minute behind them.

“Hey, we won!” she said.

Typically, once crews finish the race they pull into harbor at Dauphin Island for a trophy ceremony and a night’s rest. But the Gaston brothers decided to turn around and sail back home, assuming they’d beat the storm; others made the same choice. The brothers headed north along the bay’s western shore. During the race Ron had used an out-of-service iPhone to track their location on a map. He slipped it into a pocket and sat back on the “trampoline”—the fabric deck between the two hulls.

Shortly before 3 p.m., he and Hana watched as storm clouds rolled toward them from the west. A heavy downpour blurred the western horizon, as though someone had smudged it with an eraser. “We may get some rain,” Ron said, with characteristic understatement. But they seemed to be making good time—maybe they could make it to the Buccaneer Yacht Club, he thought, before the rain hit.

Hana glanced again and again at a hand-held GPS and was amazed at the speeds they were clocking. “Thirteen knots!” she told Ron. Eventually she looped its cord around her neck so she could keep an eye on it, then tucked the GPS into her life preserver so she wouldn’t lose it.

By now the storm, which had first come alive in Texas, had crossed three states to reach the western edge of Mobile Bay. Along the way it developed three separate storm cells, like a three-headed Hydra, each dense with cold air and icy particulates held aloft by a warm updraft, like a hand cradling a water balloon. Typically a cold mass will simply dissipate, but sometimes as a storm moves across a landscape something interrupts the supporting updraft. The hand flinches, and the water balloon falls: a downburst, pouring cold air to the surface. “That by itself is not an uncommon phenomenon,” says Mark Thornton, a meteorologist and member of U.S. Sailing, a national organization that oversees races. “It’s not a tragedy, yet.”

During the regatta, an unknown phenomenon—a sudden shift in temperature or humidity, or the change in topography from trees, hills and buildings to a frictionless expanse of open water—caused all three storm cells to burst forth at the same moment, as they reached Mobile Bay. “And right on top of hundreds of people,” Thornton said. “That’s what pushes it to historic proportions.”

At the National Weather Service’s office in Mobile, meteorologists watched the storm advance on radar. “It really intensified as it hit the bay,” recalled Jason Beaman, the meteorologist in charge of coordinating the office’s warnings. Beaman noted the unusual way the storm, rather than blow itself out quickly, kept gaining in strength. “It was an engine, like a machine that keeps running,” he said. “It was feeding itself.”

Storms of this strength and volatility epitomize the dangers posed by a climate that may be increasingly characterized by extreme weather. Thornton said that it wouldn’t be “scientifically appropriate” to attribute any storm to climate change, but said “there is a growing consensus that climate change is increasing the frequency of severe storms.” Beaman suggests more research should be devoted to better understanding what’s driving individual storms. “The technology we have just isn’t advanced enough right now to give us the answer,” he said.

On Mobile Bay, the downbursts sent an invisible wave of air rolling ahead of the storm front. This strange new wind pushed Ron and Hana faster than they had gone during any point in the race.

“They’re really getting whipped around,” he told a friend. “This is how they looked during Katrina.”

A few minutes later the MRD’s director called from Dauphin Island. “Scott, you’d better get some guys together,” he said. “This is going to be bad. There are boats blowing up onto the docks here. And there are boats out on the bay.”

The MRD maintains a camera on the Dauphin Island Bridge, a three-mile span that links the island to the mainland. At about 3 p.m., the camera showed the storm’s approach: whitecaps foaming as wind came over the bay, and beyond that rain at the far side of the bridge. Forty-five seconds later, the view went completely white.

Under the bridge, 17-year-old Sarah Gaston—Ron’s daughter, and Hana’s best friend—struggled to control a small boat with her sailing partner, Jim Gates, a 74-year-old family friend.

“We just were looking for any land at that point,” Sarah said later. “But everything was white. We couldn’t see land. We couldn’t even see the bridge.”

The pair watched the jib, a small sail at the front of the boat, ripping in slow motion, as if the hands of some invisible force tore it from left to right.

Farther north, the Gaston brothers on their catamarans were getting closer to the Buccaneer Yacht Club, on the bay’s western shore.

Lightning crackled. “Don’t touch anything metal,” Ron told Hana. They huddled on the center of their boat’s trampoline.

Sailors along the edges of the bay had reached a decisive moment. “This is the time to just pull in to shore,” Thornton said. “Anywhere. Any shore, any gap where you could climb on to land.”

Ron tried. He scanned the shore for a place where his catamaran could pull in, if needed. “Bulkhead...bulkhead...pier...bulkhead,” he thought. The walled-off western side of the bay offered no harbor. Less than two miles behind, his brother Shane, along with Shane’s son Connor, disappeared behind a curtain of rain.

“Maybe we can outrun it,” Ron told Hana.

But the storm was charging toward them at 60 knots. The world’s fastest boats—giant carbon fiber experiments that race in the America’s Cup, flying on foils above the water, requiring their crew to wear helmets—couldn’t outrun this storm.

Lightning flickered in every direction now, and within moments the rain caught up. It came so fast, and so dense, that the world seemed reduced to a small gray room, with no horizon, no sky, no shore, no sea. There was only their boat, and the needle-pricks of rain.

The temperature tumbled, as the downbursts cascaded through the atmosphere. Hana noticed the sudden cold, her legs shaking in the wind.

Then, without warning, the gale dropped to nothing. No wind. Ron said, “What in the wor”—but a spontaneous roar drowned out his voice. The boat shuddered and shook. Then a wall of air hit with a force unlike anything Ron had encountered in a lifetime of sailing.

The winds rose to 73 miles per hour—hurricane strength—and came across the bay in a straight line, like an invisible tsunami. Ron and Hana never had a moment to let down their sails.

The front of the Kyla rose up from the water, so that it stood for an instant on its tail, then flipped sideways. The bay was only seven feet deep at that spot, so the mast jabbed into the mud and snapped in two.

Hana flew off, hitting her head on the boom, a horizontal spar attached to the mast. Ron landed between her and the boat, and grabbed her with one hand and a rope attached to the boat with the other.

The boat now lay in the water on its side, and the trampoline—the boat’s fabric deck—stood vertical, and caught the wind like a sail. As it blew away, it pulled Ron through the water, away from Hana, stretching his arms until he faced a decision that seemed surreal. In that elongated moment, he had two options: He could let go of the boat, or Hana.

He let go of the boat, and in seconds it blew away beyond the walls of their gray room. The room seemed to shrink with each moment. Hana extended an arm and realized she couldn’t see beyond her own fingers. She and Ron both still wore their life jackets, but eight-foot swells crashed on them, threatening to separate them, or drown them on the surface.

The two wrapped their arms around each other, and Hana tucked her head against Ron’s chest to find a pocket of air free from the piercing rain.

In the chaos, Ron thought, for a moment, of his daughter. But as he and Hana rolled together like a barrel under the waves, his mind went blank and gray as the seascape.

Sarah and Jim’s boat had also risen up in the wind and bucked them into the water.

The mast snapped, sending the sails loose. “Jim!” Sarah cried out, trying to shift the sails. Finally, they found each other, and dragged themselves back into the wreckage of their boat.

About 30 miles north, a Coast Guard ensign named Phillip McNamara stood his first-ever shift as duty officer. As the storm bore down on Mobile Bay, distress calls came in from all along the coast: from sailors in the water, people stranded on sandbars, frantic witnesses on land. Several times he rang his superior, Cmdr. Chris Cederholm, for advice about how to respond, each time with increasing urgency.

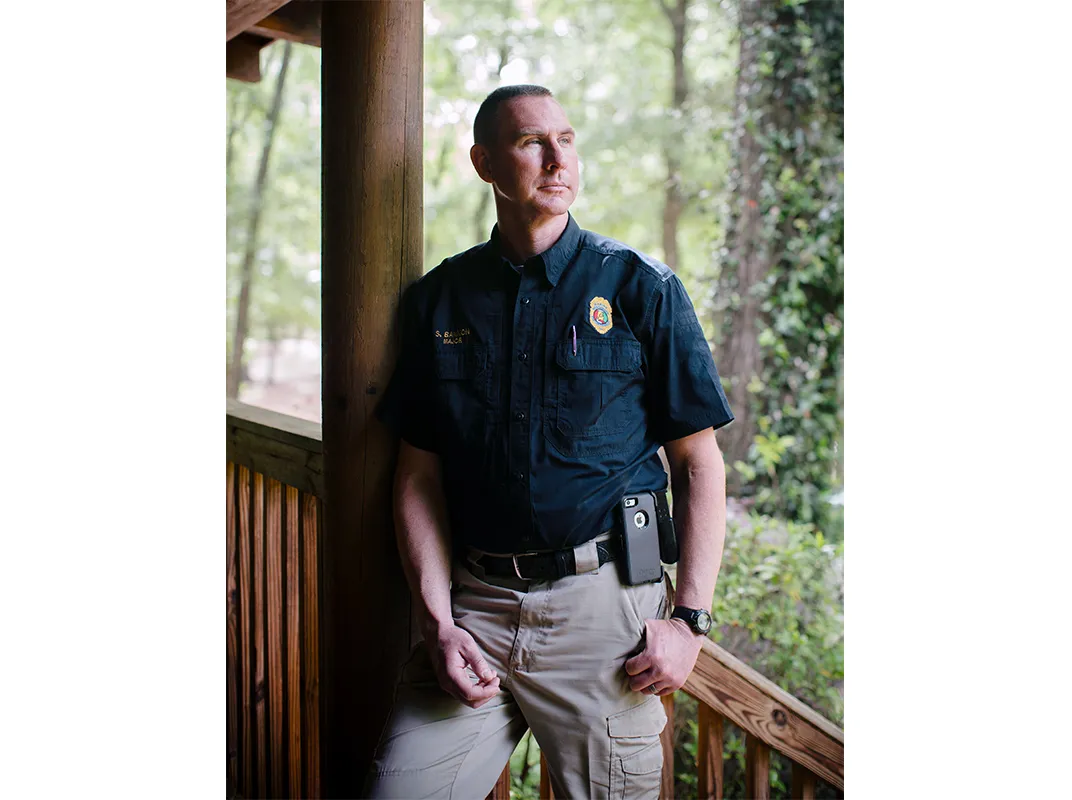

About 15 miles inland, Scott Bannon, a major with Alabama’s Marine Resources Division, looked up through the high windows in his log home west of Mobile. Bannon lives on a pine-covered hill and has seen so many hurricanes blow through that he can measure their strength by the motion of the treetops.

“By the third call it was clear something big was happening,” Cederholm said recently. When Cederholm arrived at the station, he understood the magnitude of the disaster—scores of people in the water—and he triggered a Coast Guard protocol called a “Mass Rescue Operation,” summoning a response from air, land and sea.

As authorities scrambled to grasp the scale of the storm, hundreds of sailors on the bay struggled to survive it. The wind hit the Luitens’ Razr so fast it pinned the sails to the mast; there was no way to lower them. The wind flipped the boat, slinging the crew—Lennard, his father, Robert, 71-year-old Jimmie Brown, and teenage friends Adam Clark and Jacob Pouncey—into the water. Then the boat barrel-rolled, and Lennard and Brown were briefly scooped back onto its deck before the keel snapped and they were tossed once again, this time in the other direction.

Brown struggled in a raincoat. Lennard, a strong swimmer, swam around the boat, searching for his dad, whom he found with Jacob. After 20 minutes or so, towering eight-foot waves threatened to drown them, and Lennard struck out for the shore to find help.

Normally, a storm’s hard edge blows past in two or three minutes; this storm continued for 45 minutes.

An experienced sailor named Larry Goolsby, captain of a 22-foot boat named Team 4G , was in sight of the finish line when the storm came on; he and two crew members had just moments to ease the sails before the wind hit. The gale rolled the boat over twice, before a much heavier 40-foot vessel hove into view upwind. The bigger boat was moving with all the force of the storm at its back, and bearing down on the three men.

One shouted over the wind, “They’re going to hit us!” just as the bigger boat smashed into the Team 4G , running it over and dragging the smaller boat away.

The crew members had managed to jump clear into the water just before impact. In the same instant, Goolsby grabbed a rope dangling from the charging boat and swung himself up onto its deck. Reeling, he looked back to see his crew mates in the water, growing more distant by the second. None were wearing life jackets. Goolsby snatched a life ring from the deck of the runaway vessel and dove back into the water, hoping to save his friends.

Similar crises unfolded across the bay. A 26-foot boat named the Scoundrel had finished the race and turned north when the storm hit. The wind knocked the boat on its side before the captain had time to let down the sails. As the boat lay horizontal, he leaped into the water, let loose the sails, and then scrambled back aboard as the ship righted itself. But one crew member, he saw, 27-year-old Kristopher Beall, had fallen in, and was clinging to a rope trailing the boat. The 72-year-old captain tried to haul him in as Beall gasped for air amid the waves.

A dozen Coast Guard ships from Mississippi to Florida responded, along with several airplanes, helicopters and a team of searchers who prowled the coastline on all-terrain vehicles. People on horses searched the bay’s clay banks for survivors.

At the Coast Guard outpost on Dauphin Island, Bannon, the marine resources officer, made call after call to the families and friends of boat owners and captains, trying to work out how many people might be missing. The regatta organizers kept a tally of captains, but not of others who were on board the boats.

Cederholm, the Coast Guard commander, alerted the military chain of command, all the way up to three-star admiral William Lee. “I’ve never seen anything like this,” the 34-year veteran of the sea told Cederholm.

Near the Dauphin Island Bridge, a Coast Guard rescue boat picked up Sarah Gaston and Jim Gates. She had suffered a leg injury and hypothermia, and as her rescuers pulled her onto their deck, she went into shock.

Ron and Hana were closer to the middle of the bay, where the likelihood of rescue was frighteningly low. “All you can really see above water is someone’s head,” Bannon explained later. “A human head is about the size of a coconut. So you’re on a ship that’s moving, looking for a coconut bobbing between waves. You can easily pass within a few feet and never see someone in the water.”

Ron and Hana had now been in the water for two hours. They tried to swim for shore, but the waves and current locked them in place. To stave off the horror of their predicament, Hana made jokes. “I don’t think we’re going to make it home for dinner,” she said.

“Look,” Ron said, pulling the phone from his pocket. Even though it was out of service, he could still use it to make an emergency call. At the same moment, Hana pulled the GPS unit from her life jacket and held it up.

Ron struggled with wet fingers to dial the phone. “Here,” he said, handing it to Hana. “You’re the teenager.”

She called 911. A dispatcher answered: “What is your emergency and location?”

“I’m in Mobile Bay,” Hana said.

“The bay area?”

“No, ma’am. I’m in the bay. I’m in the water.”

Using the phone and GPS, and watching the blue lights of a patrol boat, Hana guided rescuers to their location.

As an officer pulled her from the water and onto the deck, the scaffolding of Hana’s sense of humor started to collapse. She asked, “This boat isn’t going to capsize too, is it?”

Ron’s brother and nephew, Shane and Connor, had also gone overboard. Three times the wind flipped their boat on its side before it eventually broke the mast. They used the small jib sail to fight their way toward the western shore. Once on land, they knocked on someone’s door, borrowed a phone, and called the Coast Guard to report that they’d survived.

The three-man crew of the Team 4G clung to their commandeered life ring, treading water until they were rescued.

Afterward, the Coast Guard hailed several volunteer rescuers who helped that day, including Scott Godbold, who had come out with his wife, Hope, to watch their son Matthew. As the sun started to set that evening, the Godbolds sailed into the Coast Guard’s Dauphin Island station with three survivors.

“It was amazing,” said Bannon. The odds against finding even one person in more than 400 square miles of choppy sea were outrageous. Behind Godbold’s sailboat, they also pulled a small inflatable boat, which held the body of Kristopher Beall.

After leaving Hope and the survivors at the station, Godbold was joined by his father, Kenny, who is in his 70s, and together they stepped back onto their boat to continue the search. Scott had in mind a teenager he knew: Lennard Luiten, who remained missing. Lennard’s father had been found alive, as had his friend Jacob. But two other Razr crew members—Jacob’s friend, Adam, and Jimmie Brown—had not survived.

By this point Lennard would have been in the water, without a life jacket, for six hours. Night had come, and the men knew the chances of finding the boy were vanishingly remote. Scott used the motor on his boat to ease out into the bay, listening for any sound in the darkness.

Finally, a voice drifted over the water: “Help!”

Hours earlier, as the current swept Lennard toward the sea, he had called out to boat after boat: a Catalina 22 racer, another racer whom Lennard knew well, a fisherman. None had heard him. Lennard swam toward an oil platform at the mouth of the bay, but the waves worked against him, and he watched the platform move slowly from his south to his north. There was nothing but sea and darkness, and still he hoped: Maybe his hand would find a crab trap. Maybe a buoy.

Now Kenny shined a flashlight into his face, and Scott said, “Is that you, Lennard?”

Ten vessels sank or were destroyed by the storm, and 40 people were rescued from the water. A half-dozen sailors died: Robert Delaney, 72, William Massey, 67, and Robert Thomas, 50, in addition to Beall, Brown and Clark.

It was one of the worst sailing disasters in American history.

Scott Godbold doesn’t talk much about that day, but it permeates his thoughts. “It never goes away,” he said recently.

The search effort strained rescuers. Teams moved from one overturned boat to another, where they would knock on the hull and listen for survivors, before divers swam underneath to check for bodies. Cederholm, the Coast Guard commander, said that at one point he stepped into his office, shut the door and tried to stifle his emotions.

Working with the Coast Guard, which is currently investigating the disaster, regatta organizers have adopted more stringent safety measures, including keeping better records of boat crew and passenger information during races. The Coast Guard also determined that people died because they couldn’t quickly find their life preservers, which were buried under other gear, so it now requires racers to wear life jackets during the beginning of the race, on the assumption that even if removed, recently worn preservers will be close enough at hand.

Garner, the Fairhope Yacht Club’s former commodore, was dismissive of the Coast Guard’s investigation. “I’m assuming they know the right-of-way rules,” he said. “But as far as sailboat racing, they don’t know squat.”

Like many races in the U.S., the regatta was governed by the rules of U.S. Sailing, whose handbook for race organizers is unambiguous: “If foul weather threatens, or there is any reason to suspect that the weather will deteriorate (for example, lightning or a heavy squall) making conditions unsafe for sailing or for your operations, the prudent (and practical) thing to do is to abandon the race.” The manual outlines the responsibility of the group designated to run the race, known as the race committee, during regattas in which professionals and hobbyists converge: “The race committee’s job is to exercise good judgment, not win a popularity contest. Make your decisions based on consideration of all competitors, especially the least experienced or least capable competitors.”

The family of Robert Thomas is suing the yacht club for negligence and wrongful death. Thomas, who worked on boats for Robert Delaney, doing carpentry and cleaning jobs, had never stepped foot on a boat in water, but was invited by Delaney to come along for the regatta. Both men died when the boat flipped over and pinned them underneath.

Omar Nelson, an attorney for Thomas’ family, likens the yacht club to a softball tournament organizer who ignores a lightning storm during a game. “You can’t force the players to go home,” he said. “But you can take away the trophy, so they have a disincentive.” The lawsuit also alleges that the yacht club did in fact initially cancel the race due to the storm, contrary to Garner’s claim about a misunderstanding about the scratch sheet, but that the organizers reversed their decision. The yacht club’s current commodore, Randy Fitz-Wainwright, declined to comment, citing the ongoing litigation. The club’s attorney also declined to comment.

For its part, the Coast Guard, according to an internal memo about its investigation obtained by Smithsonian , notes that the race’s delayed start contributed to the tragedy. “This caused confusion among the race participants and led to a one-hour delay....The first race boats finished at approximately 1350. At approximately 1508, severe thunderstorms consisting of hurricane force winds and steep waves swept across the western shores of Mobile Bay.” The Coast Guard has yet to release its report on the disaster, but Cederholm said that, based on his experience as a search-and-rescue expert, “In general, the longer you have boats on the water when the weather is severe, the worse the situation is.”

For many of the sailors themselves, once their boats were rigged and they were out on the water, it was easy to assume the weather information they had was accurate, and that the storm would behave predictably. Given the access that racers had to forecasts that morning, Thornton, the meteorologist, said, “The best thing at that point would be to stay home.” But even when people have decent information, he added, “they let their decision-making get clouded.”

“We struggle with this,” said Bert Rogers, executive director of Tall Ships America, a nonprofit sail training association. “There is a tension between technology and the traditional, esoteric skills. The technology does save lives. But could it distract people and give them a false sense of confidence? That’s something we’re talking about now.”

Hana, who had kept her spirits buoyed with jokes in the midst of the ordeal, said the full seriousness of the disaster only settled on her later. “For a year and a half I cried any time it rained really hard,” she said. She hasn’t been back on the water since.

Lennard went back to the water immediately. What bothers him most is not the power of the storm but rather the power of numerous minute decisions that had to be made instantly. He has re-raced the 2015 Dauphin Island Regatta countless times in his mind, each time making adjustments. Some are complex, and painful. “I shouldn’t have left Mr. Brown to go find my dad,” he said. “Maybe if I had stayed with him, he would be OK.”

He has concluded that no one decision can explain the disaster. “There were all these dominoes lined up, and they started falling,” he said. “Things we did wrong. Things Fairhope Yacht Club did wrong. Things that went wrong with the boat. Hundreds of moments that went wrong, for everyone.”

In April of this year, the regatta was postponed because of the threat of inclement weather. It was eventually held in late May, and Lennard entered the race again, this time with Scott Godbold’s son, Matthew.

During the race, somewhere near the middle of the bay, their boat’s mast snapped in high wind. Scott Godbold had shadowed them, and he pulled alongside and tossed them a tow line.

Lennard was still wearing his life preserver.

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this story used the phrase “60 knots per hour.” A knot is already a measure of speed: one knot is 1.15 miles per hour.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Bryan Schutmaat | READ MORE

Bryan Schutmaat is a photographer whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine , Bloomberg Business Week , and The Telegraph . He has two books of photography, Islands of the Blest and Grays the Mountain Sends .

Matthew Teague | READ MORE

Matthew Teague is a freelance writer in Fairhope, Alabama. He has also written for Esquire , where he won a National Magazine Award in 2016.

- Classifieds

- Subscribe My Profile

- Login Logout

FLASHBACK: Recalling the 1979 Fastnet Race tragedy

August 8th, 2019 10:27 AM

By Southern Star Team

Share this article

Our special report, on the 40th anniversary, reflects on the terrifying ordeal of the Fastnet yacht race in 1979 that claimed the lives of 15 competitors.

By Robert Hume

AT 10am on Saturday August 11th 1979, a total of 303 yachts set sail from Cowes on the Isle of Wight, not realising what was ahead of them.

For skipper David Sheahan and his 17-year-old son, Matthew, on Grimalkin – one of the smallest boats (named after the witches’ cat in Macbeth ) – it was ‘the biggest challenge of their lives’.

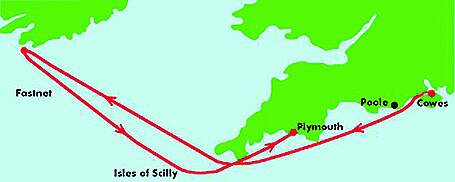

Founded in 1925, the six-day Fastnet race follows a 608-mile course to the Fastnet Rock, the most southerly point of Ireland, and back to Plymouth, via the Scilly Isles. Until that year, there had been only one death.

The 6pm shipping forecast brought news of near-perfect conditions. One yachtswoman described it ‘like going on holiday’. But, unknown to competitors, a gale was brewing some 2,000 miles away in the Atlantic.

The yachts inched down the Solent strait in very gentle wind. On Monday they were becalmed in fog off Cornwall, but about midday the fog lifted and they rounded Lands’ End. The next 300 miles would be rough and unpredictable.

Crews got the first hint of the danger to come when BBC Weather forecast Force 8 winds.

On Grimalkin , David Sheahan reduced the sails and radioed Lands’ End: ‘Getting a little choppy out here,’ he said. Fellow crewman Nick Ward observed a strange ‘ochre sky’ before things started to turn nasty.

As night fell, and the wind whipped up, yachts lay scattered across the Western Approaches, with radio antenna broken, rudders lost and masts snapped.

There was now a Force 10 storm heading their way, said the forecast. ‘We were confident we could cope with it,’ said David’s son Matthew.

But it was no ordinary storm. A 40ft wave knocked Grimalkin on its side, catapulting Matthew overboard. As hypothermia set in, he said, ‘brains slowed down’ – he ‘forgot’ how to do his jacket zip up.

Yachtsmen were thrown out of their cockpits and left dangling in the sea by their safety harnesses. In the cabins, galley stoves and tins of food flew from side to side with every lurch.

Many yachts had no radios and instead launched distress flares. The crew of the Trophy clambered into their liferaft – a decision that would cost three of them their lives.

‘The most frightening aspect was that so many things happened at night,’ said Barry O’Donnell on Sundowner. ‘The noise of the waves was incredible … every oncoming wave blacked out everything else …’

Throughout Tuesday the storm ran unabated. Helicopters were scrambled from Kinloss and Culdrose but huge waves and Force 11 winds made rescue attempts impossible.

‘Nothing we can do for you at the moment … Good luck!’ came back the frightening reply to David Sheahan’s Mayday call.

Moments later, Grimalkin was rolled over by a giant breaker. Matthew thought he was going to die. It made him angry. A body floated by: he knew it was his father, drowned. Meanwhile, fellow crewmen, Nick Ward and Gerry Winks, were slumped lifeless in the cockpit.

As conditions eased on Wednesday, a Dutch frigate picked up the first two dead.

Helicopter crews began plucking survivors from the ocean. They brought up Nick Ward who had been alone for half a day, battered by the waves, while his friend, Gerry, lay dying in his arms.

Even the Irish Continental Line ferry, St Killian , carrying 600 passengers and 200 cars, assisted the rescuers.

Over the next two days, many yachts ended up in Irish ports – around 40 in Crosshaven. Grimalkin , half-swamped, was found by a freighter and towed into Waterford. Regardless , skippered by Midleton businessman Ken Rohan, was rescued after six attempts and brought into Baltimore harbour; another Irish yacht, Golden Apple of the Sun , owned by Hugh Coveney, (father of the current Tánaiste Simon) was towed, rudderless, into Cork. A huge crowd welcomed the Casse Tete as it was towed into Courtmacsherry.

Only 85 yachts reached Plymouth – among them Morning Cloud , former British Prime Minister Edward Heath’s vessel.

Fifteen sailors lost their lives. Two non-competitors, and four others shadowing the race, also died. Margaret Winks, Gerry’s widow, knew she would have to scatter his ashes at sea and dreaded it: ‘I feel the sea has taken too much of him.’

On August 15th, The Washington Post ’s Christian Williams, reported: ‘No matter who takes home the trophy, this year’s Fastnet Race will be remembered as the biggest disaster in ocean-racing history.

‘By late today, there were 17 confirmed deaths and 25 yachts sunk or abandoned in the sudden gale that hit the North Atlantic between Britain and Ireland, directly on the course of the race.’

Williams described the evening on board Tenacious , Ted Turner’s yacht, which was to eventually win the ill-fated race:

‘Isn’t anyone going to carve the roast?’ [chef] Jane Potts called out to Bobby Symonette, a veteran blue-water sailor who was hurrying by to his duty station.

‘My dear,’ replied Symonette, in his calm Bahamian accent, ‘There are not many who will eat tonight. And those that do will be sorry.’

‘The storm struck Tenacious a few moments later [see photograph of the Tenacious , above, courtesy of Afloat.ie, the eventually won the race].

As Turner and his crew would learn only later, it struck the entire fleet simultaneously, and it struck with the force of a B52 attack. More than 140 sailors would require rescue by Royal Navy helicopters and search vessels of every description before the night was over.

The Royal Ocean Racing Club, sponsor of the biennial race, said 13 of the dead were British, one was Dutch and one, Frank H Ferris, was an American.’

Later, in the article, Williams recalls arriving back in the UK: ‘When Turner’s yacht docked … they knew they had been through more than just another gruelling Fastnet Race. Immediately as the boat touched shore here, one crewman leaped off and ran to the race office for news of the competition. When he returned, smiles on board faded.

‘My God,’ he reported, stunned. ‘There’s a crowd of people up there and they’re all crying and they ask you if you have heard anything about their husbands, or their boyfriends. It’s like a tragedy here, not like a race.’

One competitor told The Southern Star that deaths could have been avoided ‘if competitive zeal had taken second place to common sense’.

Crews had been warned three days earlier of Force 8 gales, claimed another, but heavy sponsorship meant they could not pull out.

THE 15 COMPETITORS WHO DIED (yachts in brackets):

Paul Baldwin, (Gunslinger); Robin Bowyer, (Trophy); Sub-Lt Russell Brown, (Flashlight); David Crisp, (Ariadne); Peter Dorey, (Cavale); Peter Everson, (Trophy); Frank Ferris, (Ariadne); William Le Fevre, (Ariadne); John Puxley, (Trophy); Robert Robie, (Ariadne); David Sheahan, (Grimalkin); Sub-Lt Charles Steavenson, (Flashlight); Roger Watts, (Festina Tertia); Gerrit-Jan Willahey, (Veronier II); Gerald Winks, (Grimalkin).

Rescue as vivid today as it was 40 years ago

By Jackie Keogh

THE Robert – a 48ft Watson lifeboat – was back in Baltimore on Friday, August 2nd, [see below, photo by Anne Minihane], and with it came a raft of memories for the crew who were called out on Monday, August 13th 1979, the night of the Fastnet Race Disaster.

‘It was great to see the old lifeboat back in her colours with Baltimore Lifeboat on her stern,’ said Kieran Cotter, coxswain of Baltimore RNLI.

It was in Baltimore for the 40th anniversary of the Fastnet Race Disaster and The Robert may stay for the 100th RNLI anniversary, which will take place on September 8th.

The vessel represents many years of life-saving service, according to Kieran, who admitted: ‘I rarely look back on things but this is one night that is still vivid in my memory.’

The Fastnet Race started, as it always does, in Cowes in the Isle of Wight on Saturday, August 11th, but it was a severe summer storm that resulted in lives being lost in the treacherous seas.

Meanwhile, off the Fastnet Rock – which is the picturesque but frequently treacherous turning point in the race –the crew of Baltimore RNLI worked from 10pm to 8am to bring a yacht and its crew to safety.

Kieran [pictured, below] set the scene by pointing out that 40 years ago things were vastly different to how they are today. Of course, the route remains unchanged, but today the boats are bigger, much better equipped, and the crew can no longer be leisure-time enthusiasts. They must have a proven track record that includes training and serious competitive race experience.

Reading from the yellowing pages of the 40-year-old record book, Kieran confirmed that the crew received the call at 10.05pm and they were mobilised by 10.15pm.

Richard Bushe, the acting hon secretary, set out the timeline: he recorded how the keeper at the Fastnet Lighthouse – in the days when it was manned – notified them that there was a vessel in difficulty.

The boat they initially went in search of had, like 20 other boats, made it safely to Schull, but on their way back to Baltimore the crew received another message to go to the assistance of a yacht, The Regardless , after it lost its rudder.

Reading from the record book, Kieran said: ‘The wind was Force 9, South West. The seas were very high and the visibility was poor.’ When asked if that translates as ‘frightening,’ Kieran said: ‘No, but the conditions were difficult.’

In the next breath, Kieran admitted that the crew – which included Christy Collins, coxswain; Mick O’Connell, mechanic; Paul O’Regan, Peter O’Regan, Kieran Cotter, Noel Cottrell, Pat Harrington and Con Cahalane – all of whom are now deceased except for Kieran and Peter O’Regan – had to reconnect the tow-line five times.

Richard Bushe’s note that states: ‘This must have been the worst weather The Robert was called out on when on service.’

Kieran said the crew were used to going out in bad weather. Most of them had been fishermen, or involved in boating, and all were trained as lifeboat crew.

Equally, out of the nine-man crew on The Regardless , Kieran said a few of them were professional sailors and they were able to cope with the situation as she drifted.

They arrived back in Baltimore at 8am and they assisted in mooring The Regardless and ensuring that the crew were given the same warm welcome that this community offers every stranded sailor.

The RNLI crew barely had time to put shoe leather on soil when they got another call to go back out to the aid of The Marionette , a British yacht that was also rudderless and adrift. The vessel was 25 miles south of the Galley and 50 miles from the Baltimore station, and it was in Force 6 winds that the yacht – which had 12 people on board – was towed back to Baltimore.

The Robert could only do nine miles in the hour so it wasn’t until mid-afternoon that they found The Marionette and it wasn’t until 10.30pm that The Robert was housed, making it a marathon 24-hour service for the crew, which, on this occasion, included John O’Regan.

About 100 miles away, off the Scilly Isles, conditions were worsening as the weather front moved in and that year the Fastnet Race claimed the lives of 15 competitors and four more on an American support boat.

The majority of them had been on the smaller boats – the larger ones having made it in faster time to the Fastnet. And it was not until the Wednesday and Thursday that the full extent of the loss of life at sea was confirmed.

Kieran said: ‘You have to remember that communication was nothing like it is today. There were no mobile phones and not every boat had a VHF radio. And if they did have a radio, they were not able to transmit very far.’

Kieran also recalled the rescue of The Rambler during the 2011 Fastnet Race. He said The Rambler was one of the foremost racing boats in the world, but after rounding the Fastnet its rudder cracked, fell off, and she capsized. There were 21 crew on board and 16 were taken off the upturned hull by Baltimore RNLI, while five more – including the owner, George David – were rescued from the sea.

The Fastnet Race continues to be a hugely prestigious race with over 300 boats taking part as they start at Cowes, round the Fastnet, and finish in Plymouth.

Baltimore RNLI’s coxswain is 64, making him just 24 when the Fastnet Race Disaster happened. He said: ‘It was a massive tragedy, but, over the last 45 years that I have worked on the lifeboat, there have been more than 50 casualties in our area, plus the Betelgeuse, which claimed another 50.’

He named the five people who died on the Tit Bonhomme , the four who died on the St Gervais ; the three who died after being swept off the rocks in Baltimore; the two who died in Audley Cove; and all those tragic deaths that happened one at a time.

‘The sea,’ said Kieran, ‘is a dangerous place.’

'The sea was mountainous' recalls Fastnet keeper

By Paddy Mulchrone

A LIGHTHOUSE keeper on Fastnet Rock during the world’s worst yacht race disaster is to lead a remembrance service for the 15 sailors who perished in the treacherous storm 40 years ago this month.

The annual graveyard mass on Cape Clear will honour the dead of the 1979 Fastnet tragedy and pay tribute to the many hundreds who risked their lives to save many more.

One of the readings will be by Gerald Butler, 69, [pictured, below, at Galley Head], of Clonakilty, who was one of three keepers on duty that fateful night.

The mass takes place at 3pm on Sunday August 18th and all local mariners and seafarers – and anyone wishing to participate – will be welcome. Organiser Séamus Ó Drisceoil said: ‘We hope to finish off the Service with a rendering of the lifeboat song, Home from the Sea and would welcome in particular local singers who might join us for the occasion.’

Following the service, at 4.30pm at Cape Clear Heritage Centre, there will be an unveiling of a painting of Gerald Butler by Welsh artist, Dan Llywelyn Hall. Finger food and will be provided and all are welcome.

As one of the three lighthouse keepers working at the Fastnet lighthouse, Gerald saw first-hand the deadly swells and mountainous waves that led to the deaths of 15 people.

‘It was such a horrific event. The storm just popped up out of the blue,’ said Castletownbere-born Gerald. ‘It blew with such a rage and strength that the sea was mountainous. During the course of the entire night, it was yacht after yacht after yacht getting into trouble and calling for help.’

The Heritage Centre features an audio visual presentation on the Fastnet Rock, which includes coverage of the 1979 race which changed the face of ocean racing forever, heralding the introduction of compulsory safety measures.

The RNLI says a combination of factors – a freak storm, inadequate communications and a lack of safety measures that are standard in yacht racing today – was to prove fatal in 1979, as many crews were unprepared for the turmoil about to hit them and were too far out to sea to turn back.

Data from the storm revealed that as a front of low pressure passed over the Western Approaches, a column of cold airt crashed down from the stratosphere, splitting it into many smaller systems and “turbocharging” the wind.

There was no Global Satellite Positioning (GPS), no terrestrial navigation and many had no radio communications.

Survivor Phil Crbbin, crew on the yacht Eclipse , said later: ‘Even in heavy conditions at night, it was not automatic for everybody on deck to wear lifejackets and harnesses in those days – that became a requirement as a result of this race.’

Only 86 of 303 starting boats finished. There were 194 retirements; 25 boats sunk or were disabled and abandoned; 75 turned upside down; five boats were lost ‘believed sunk’ and 15 sailors were drowned.

Some 31 RNLI lifeboats put to sea, served 170 hours and towed or escorted 18 yachts, with more than 100 aboard, to safety. At the height of the storm, Baltimore lifeboat was at sea for 24 hours and Courtmacsherry’s for 20 hours.

The rescue was co-ordinated by the Irish and UK Coast Guards. An incredible 4,000 personnel were involved, including British, Irish and Dutch naval vessels and aircraft. The RNLI, Royal Navy and RAF led the way.

Said an RNLI spokesman: ‘It is certain that, without the selfless determination of these courageous rescuers, the death toll would have been even higher.’

The disaster led to ‘significant changes and improvements’ to yacht design, safety measures and equipment.

Crews must now pre-qualify for Ocean races. They must have VHF radio and safety harnesses. Yachts have been re-engineered to give more stability and crews are advised not to abandon ship until sinking is inevitable.

Technical advances have led to the introduction of global positioning satelleite (GPS) equipment and personal locator beacons.

Race organisers the Royal Ocean Racing Club (RORC) remembered the dead of 40 years ago at a special service last weekend in Cowes, overlooking the starting line for the race.

The RORC will also be hosting an exhibition of paintings by artist Dad Llywelyn Hall entitled ‘Fastnet – a portrait’ at the RORC’s London headquarters at 20 St James’s Pl in south-west London from September 16th to 22nd.

Artwork will be available to buy and donations from each sale will be made to the RNLI.

Click here to sign up to our mailing list and get the best of West Cork delivered straight to your inbox.

Related content

Out and about in west cork.

2 hours ago

E-scooter rider is caught with cocaine in Clonakilty

4 hours ago

Ghosts in the machinery: How West Cork farmers reacted to technology over the years

Breaking: new into vice president is west cork native, recommended, check out this weekend's west cork league fixtures.

- Story Highlights

- Next Article in World Sport »

LONDON, England (CNN) -- It is still remembered as one of the worst days in the history of modern sailing.

The Fastnet race still remains one of the biggest events in the yachting calendar.

Yet the Fastnet tragedy of 1979 in which 15 people were killed and ex-British leader Edward Heath went missing helped to usher in a new era of improved safety in the sport.

It was 30 years ago today that a freak storm struck over 300 vessels competing in the 600-mile yacht race between England and Ireland.

Mountainous seas and vicious high winds sunk or put out of action 25 boats.

The British rescue attempt turned into an international effort with a Dutch warship and trawlers from France also joining the search.

In spite of the biggest rescue operation launched by the UK authorities since the Second World War a total of 15 people died. Some of them drowned and others succumbed to hypothermia. Six of those lost went missing after their safety harnesses broke.

"It was a catastrophic event that had far-reaching consequences for the sport, the biggest of which was in the design and safety of the boats," Rodger Witt, editor of the UK-based magazine Sailing Today told CNN.

"Most people in the sailing community at the time knew someone who was involved in one way or another. I had a friend who lost his father. It was devastating."

In total 69 yachts did not finish the race. The former British prime minister, Edward Heath disappeared at the height of the storm, though he later returned to shore safe from harm. The corrected-time winner of the race was the yacht "Tenacious", owned and skippered by Ted Turner, the founder of CNN.

Witt said that in the aftermath of the disaster the rules governing racing were tightened to ensure boats carried more ballast. Improvements were also made to the safety harnesses that tied crewmen to their boats, many of which proved ineffective in the tragedy. It also became mandatory for all yachts to be fitted with radio communication equipment and all competitors were expected to hold sailing qualifications to take part.

At the time of the tragedy the Fastnet race was the last in a series of five races which made up the Admiral's Cup competition, the world championship of yacht racing.

- Yachting: No sport for the faint-hearted

- 'Sail-plane' to attempt world speed record

- Norman Foster's superyacht

Competitors from around the globe attempted the route which sets off from the Isle of Wight, off the English south coast, and rounds the Fastnet rock on the southeast coast of Ireland.

Roger Ware was in charge of handling press for the event on behalf of the organizers, the Royal Ocean Racing Club. Ware said that even today the tragedy "still spooks me." The racers set off on a Saturday but it wasn't till three days later that the authorities in the English coastal town of Plymouth realized there was a problem.

The press team was based at the Duke of Cornwall hotel in Plymouth and early Tuesday morning Ware got a call from his superiors to go to the hotel immediately in order to field calls from journalists.

"The night before we'd noticed high winds but there'd been no forecast of bad weather so we didn't think much of it," Ware told CNN. "As the morning progressed though, we heard that more and more boats were missing. It became obvious a tragedy was unfolding."

Ware said the worst part for him was fielding calls from concerned relatives. "The Royal Ocean Racing Club headquarters was overloaded so calls were getting transferred to the press team.

Share this on:

Sound off: your opinions and comments, post a comment, from the blogs: controversy, commentary, and debate, sit tight, we're getting to the good stuff.

Listen Live

The Fastnet Race Disaster: Navy Heroes Speak 40 Years On

A helicopter crewman hangs from a winch to check the battered yacht Grimalkin for possible survivors (Picture: PA).

Competitors in the 1979 Fastnet Race were in the middle of a 605-mile yachting event, from Cowes to Fastnet Rock and then to Plymouth, when an unexpected storm wreaked havoc.

With hundreds of sailors facing life-threating conditions, the Royal Navy sent emergency calls to anyone with rescue experience, an urgent plea to help with what would become the UK's largest peacetime rescue-mission.

The storm took 19 lives in total, though 130 were saved by efforts from the UK, Ireland and the Netherlands.

As part of the massive rescue operation, 15 RNAS Culdrose helicopters flew for 200 hours to save 75 stranded sailors.

Albie Fox, a former Royal Navy Wessex pilot, was woken at 5am on 11 August 1979, during the 28th Fastnet Race.

“The phone call was, 'all hell is breaking loose, could you get your backside in here, Sir?'”

Mr Fox's crew were sent flying, tasked with finding the 'Camargh' vessel.

“She was in dire straits, her rigging was flapping… her mast was going backward and forward so there was no way we could lift them off the deck.

"We had to persuade them to dive one at a time into the water."

The crew then hooked each person on to a harness, bringing them onboard the aircraft one-by-one.

Watch: Albie Fox spoke to Forces News about his mission

Keith Thompson, a former Sea King Pilot with the Royal Navy, was also part of the operation after receiving the call-out from the service.

Taking note of the vessels in danger, the scale of the emergency soon became clear.

"I was writing on my knee pad with a chinagraph pencil and running out… I started to write on the windscreen of the helicopter."

Although there were a number of vessels to look out for, the amount of water to be searched provided a huge challenge, time continuing to run down.

The Sea King crew were told that 10 to 12 yachts could be found “anywhere between land’s end and the Fastnet rock."

“You could see the ashen look on their faces, the relief of being somewhere safe, out of the water.”

Watch: Keith Thompson told Forces News about the challenge facing his team in 1979

At the time, RNAS Culdrose was on summer leave, a lot of equipment undergoing maintenance, a rescue operation was a tall order.

Conditions were pushing the aircraft available to their limits.

"We normally do a 40-foot, automatic hover, the Sea King couldn’t cope with that because the waves were about 40-feet high as well."

The sea was so rough, so much white water and big waves, it was very difficult to spot anything in the water.

Adrenaline and a high sense of responsibility pushed the teams to continue non-stop with their search, only feeling the exhaustion at the end of the day.

"We did two, four-hour trips… we just kept going…"

Over the next couple of days, Mr Thompson and his crew flew back over the scene several times, double-checking that any remaining vessels had in fact been evacuated.

For Mr Fox, the search continues to be replayed in his head to this day:

“I flew 13 hours on that day… It’s the thing that always haunted me – that I might have flown over somebody.

“For a few years after that event, it obviously played on my mind, knowing that we may have flown over somebody and not seen them.”

Related topics

Join our newsletter.

Please select at least one newsletter to subscribe to:

Pilots-eye view of chipmunk aerobatics

Nato allies train as one on exercise allied spirit 24, sneak peek of the block ii chinook helicopter, most popular.

Shapps steps in to ensure Edinburgh Castle's historic One O'Clock Gun won't be silenced

Unhappy landings: Russians making mistakes that give away their own fake aircraft

Commandos' new £10m snowmobiles will enhance Arctic lethality for elite force

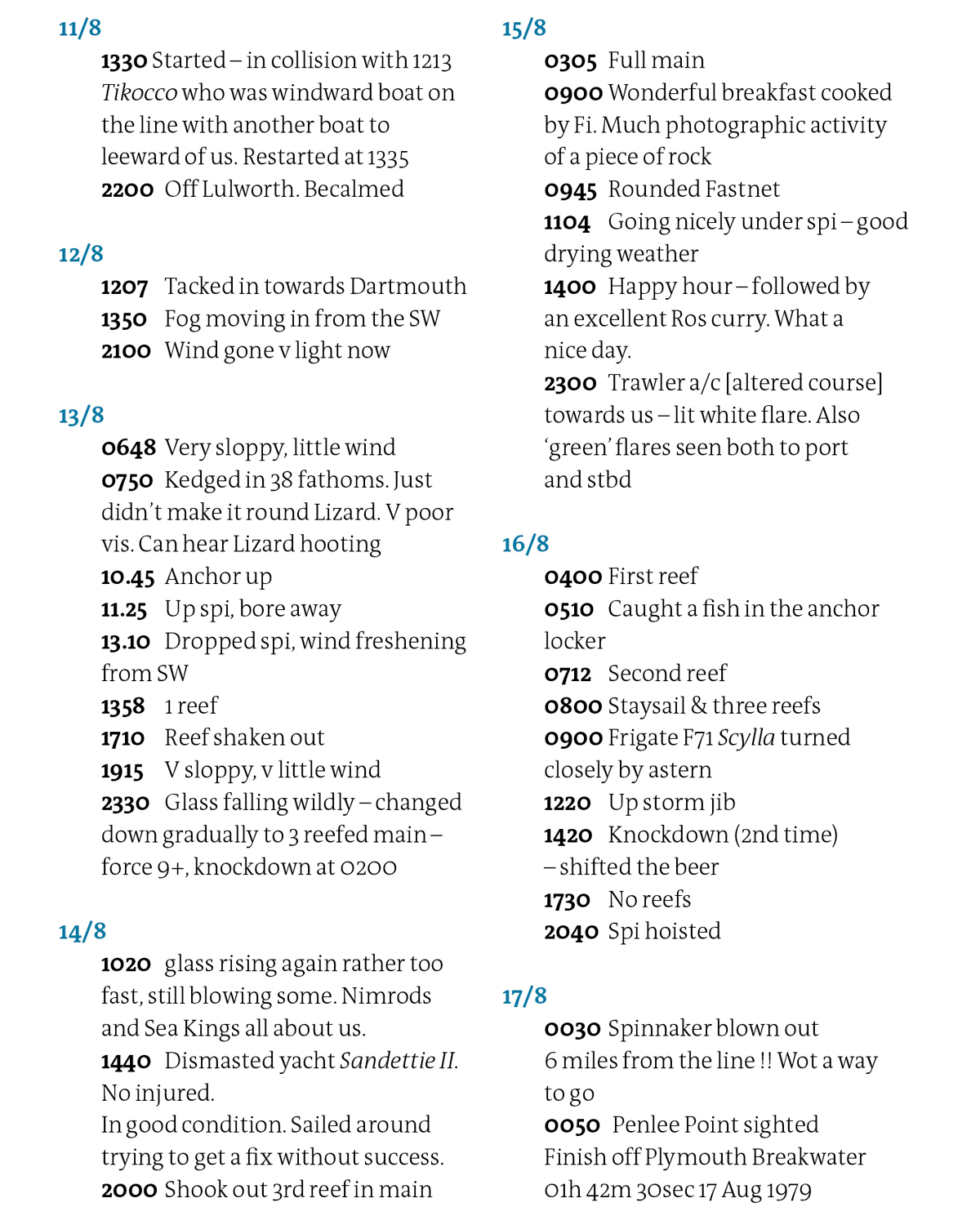

Raf parachutes more food and water into gaza, how sikh soldiers wear the turban in the military, head of the army supports new museum plans to house artillery pieces, latest stories.