The Soling is a 26.75ft fractional sloop designed by Jan Linge and built in fiberglass by Abbott Boats Inc. since 1966.

The Soling is a light sailboat which is a very high performer. It is very stable / stiff and has a good righting capability if capsized. It is best suited as a racing boat.

Soling for sale elsewhere on the web:

Main features

| Model | Soling | ||

| Length | 26.75 ft | ||

| Beam | 6.25 ft | ||

| Draft | 4.25 ft | ||

| Country | United states (North America) | ||

| Estimated price | $ 0 | ?? |

Login or register to personnalize this screen.

You will be able to pin external links of your choice.

See how Sailboatlab works in video

| Sail area / displ. | 23.26 | ||

| Ballast / displ. | 56.17 % | ||

| Displ. / length | 122.42 | ||

| Comfort ratio | 13.79 | ||

| Capsize | 1.90 |

| Hull type | Monohull fin keel with spade rudder | ||

| Construction | Fiberglass | ||

| Waterline length | 20.25 ft | ||

| Maximum draft | 4.25 ft | ||

| Displacement | 2277 lbs | ||

| Ballast | 1279 lbs | ||

| Hull speed | 6.03 knots |

We help you build your own hydraulic steering system - Lecomble & Schmitt

| Rigging | Fractional Sloop | ||

| Sail area (100%) | 251 sq.ft | ||

| Air draft | 0 ft | ?? | |

| Sail area fore | 104.55 sq.ft | ||

| Sail area main | 146.48 sq.ft | ||

| I | 24.60 ft | ||

| J | 8.50 ft | ||

| P | 27.90 ft | ||

| E | 10.50 ft |

| Nb engines | 1 | ||

| Total power | 0 HP | ||

| Fuel capacity | 0 gals |

Accommodations

| Water capacity | 0 gals | ||

| Headroom | 0 ft | ||

| Nb of cabins | 0 | ||

| Nb of berths | 0 | ||

| Nb heads | 0 |

Builder data

| Builder | Abbott Boats Inc. | ||

| Designer | Jan Linge | ||

| First built | 1966 | ||

| Last built | 0 | ?? | |

| Number built | 0 | ?? |

Other photos

Modal Title

The content of your modal.

Personalize your sailboat data sheet

Soling Sailboat: The Ultimate Guide to Racing and Cruising

by Emma Sullivan | Jul 19, 2023 | Sailboat Maintenance

Short answer: Soling sailboat

The Soling is a popular one-design keelboat introduced in 1965. It is a three-person racing yacht known for its stability, durability, and competitive performance. With a length of 27 feet and strict class rules, it has been sailed competitively around the world in various championships and is highly regarded within the sailing community.

Introduction to the Soling Sailboat: A Comprehensive Guide

Are you ready to embark on a sailing adventure that will test your skills, challenge your wit, and ignite your passion for the open sea? Look no further than the Soling sailboat – a remarkable vessel that has captured the hearts of sailors around the world with its thrilling performance and undeniable charm. In this comprehensive guide, we will dive deep into everything you need to know about this legendary sailboat.

History and Origins:

The story of the Soling sailboat begins in Norway in 1965 when designer Jan Linge set out to create a boat that would excel in both club racing and international competition. His vision resulted in the birth of what would become one of the most successful keelboats of all time – the Soling. Since then, it has been chosen as an Olympic class three times and has earned an esteemed reputation for its excellent sailing characteristics.

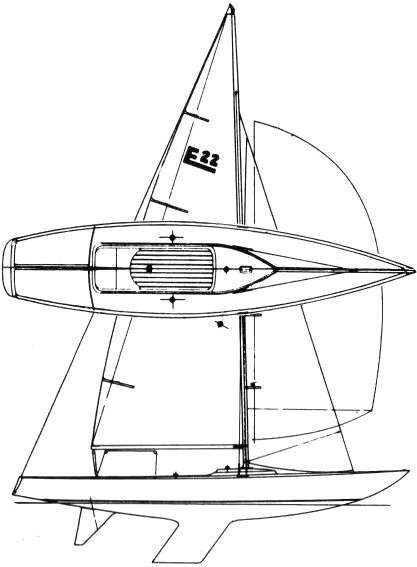

Design and Features:

The allure of the Soling sailboat lies not only in its rich history but also in its impeccable design. With a length overall (LOA) of 8.22 meters (or 27 feet), it strikes a perfect balance between agility and stability on the water. The single-masted rig configuration allows for effortless handling, while its moderate displacement ensures superb upwind performance.

This beauty comes with other noteworthy features as well. Its powerful hull design facilitates easy planning while maintaining control even at high speeds – a true testament to balanced engineering. The self-bailing cockpit prevents any unwanted accumulation of water, ensuring dry sailing even during intense races or choppy offshore adventures.

Performance:

When it comes to exhilarating performance, few sailboats can rival the Soling. Its large mainsail combined with a jib provides ample power to navigate diverse wind conditions effortlessly. Whether you’re competing against fellow sailors or enjoying leisurely day sails with friends, this boat’s exceptional upwind ability will make you feel like a true master of the sea.

Moreover, the Soling sailboat’s symmetrical spinnaker reveals its prowess downwind. As it fills with wind and billows out, you’ll experience an adrenaline rush that is sure to leave a lasting impression. Brace yourself for heart-pounding moments as you ride the waves with ease, propelled by this sailboat’s remarkable speed and stability.

Community and Camaraderie:

Sailing isn’t just about mastering techniques and maneuvering a boat; it is also about forming lifelong connections with fellow sailors who share your love for the sport. The Soling sailboat boasts a vibrant global community that cherishes camaraderie both on and off the water.

From local club regattas to international competitions, Soling sailors gather to compete, exchange knowledge, and celebrate their shared passion. Connect with like-minded individuals who excel in this exhilarating realm of sailing, where learning never stops and friendships thrive.

In Conclusion:

If you’re seeking a sailboat that embodies elegance, performance, and legendary status – look no further than the Soling. With its rich history, impeccable design features, outstanding performance capabilities, and tight-knit community of enthusiasts worldwide, this extraordinary vessel offers an unparalleled sailing experience. So grab your sunscreen, hoist those sails high, and embark on an adventure that will leave you breathless – for there is nothing quite like navigating the open seas aboard a Soling sailboat!

How to Sail a Soling Sailboat: Step-by-Step Beginner’s Guide

Are you a beginner in the world of sailing? Do you dream of gliding gracefully across the open waters, harnessing the power of the wind to propel you forward? If so, you’re in luck because today we are going to take you through a comprehensive step-by-step guide on how to sail a Soling sailboat. Get ready to embark on an exciting adventure!

Step 1: Familiarize Yourself with the Soling Sailboat Before setting sail, it’s essential to become acquainted with your vessel. The Soling sailboat is a popular choice amongst sailors due to its versatility and speed. This sleek single-masted racing boat features a three-person crew, making it an excellent option for both competitive racing and recreational sailing.

Take some time to inspect every aspect of your boat, from bow (front) to stern (back), and become familiar with its different parts. Understand the purpose of each component, such as the mainsail, jib sail, rudder, tiller, and hiking straps. Knowing these details will give you confidence and enable better communication with your crewmates.

Step 2: Plan Your Route and Check Weather Conditions The next crucial step in sailing any vessel is planning your route. Familiarize yourself with local navigation charts or use a GPS system to map out your journey. Identify any potential obstacles or hazards along your path such as rocks or shallow areas that could present challenges.

Additionally, check weather conditions before setting sail. As a beginner sailor learning how to handle a Soling sailboat effectively, it is advisable to choose days when winds are moderate rather than exceptionally strong or gusty. Keep an eye out for storms or adverse weather patterns that might affect safety.

Step 3: Rigging and Setting Up Your Sailboat Now it’s time to rig and set up your Soling sailboat! Begin by assembling the mast and attaching all necessary components securely – shrouds, stays, and spreaders. Make sure all nuts and bolts are tightened correctly.

Next, hoist the mainsail up the mast by pulling on the halyard. Make sure to attach it properly to avoid any potential mishaps while sailing. Attach and set your jib sail if you plan on using it – this will increase maneuverability in higher wind conditions.

Step 4: Docking and Departure Before you embark on your sailing journey, ensure a safe departure from the dock. Double-check that your lines (ropes) are untied or cast off from the dock cleats carefully. Have one crew member gently push against another object or use an oar or boat hook to prevent any contact with other boats or docks while disembarking.

Make proper use of fenders (buoyant cushions) to protect both your Soling sailboat and neighboring vessels during departure. Remember, communication is key during this process! Assign specific roles to each crew member to ensure a smooth transition from dockside to open water.

Step 5: Sailing Techniques With all necessary preparations complete, now it’s time for the real fun – sailing! The Soling sailboat relies heavily on teamwork between crew members as you work together harmoniously to harness nature’s power effectively.

To sail upwind (towards where the wind is coming), experiment with trimming (adjusting) both your mainsail and jib sail according to wind direction using sheets (lines attached to sails). Balance steering with weight distribution – when heading upwind, lean outboard using hiking straps known as “hiking out.” This technique increases leverage against heeling forces caused by strong winds.

For downwind sailing (with the wind behind you), ease out your sails fully for maximum power utilization. Control boat speed by adjusting rudder angle while keeping a watchful eye on surrounding hazards such as swimmers or other boats.

Step 6: Safety Precautions and Emergency Procedures Always prioritize safety while sailing. Ensure every crew member wears a well-fitted personal flotation device (PFD) at all times. Additionally, designate someone as the lookout to maintain awareness of nearby vessels or potential dangers.

In case of an emergency, be well-versed in essential safety skills such as recovering a person overboard, knowing how to deploy flares or distress signals, and understanding basic first aid techniques. While emergencies are rare, knowing how to handle them effectively will provide peace of mind for you and your fellow sailors.

Sailing a Soling sailboat can be an exhilarating and fulfilling experience for beginners wanting to delve into the world of sailing. By following these step-by-step guidelines, you’ll become equipped with the knowledge needed to handle this remarkable vessel confidently.

So grab your compass, hoist those sails high, and embark on an unforgettable sailing adventure with the majestic Soling sailboat!

Top FAQs about Soling Sailboats Answered

Welcome to our blog where we answer the top FAQs about Soling Sailboats. If you’re an avid sailor or just curious about these amazing vessels, you’ve come to the right place. We’ll provide detailed professional answers while keeping it witty and clever. So, let’s dive in!

1. What is a Soling Sailboat? A Soling Sailboat is a three-person keelboat that was designed by Jan Herman Linge from Norway and first built in 1965. It quickly gained popularity due to its competitive racing nature and became an Olympic class boat in 1972.

2. Why are Soling Sailboats popular among sailors? Solings are loved by sailors for their exceptional performance and thrilling sailing experience. Their unique design allows them to maneuver well in various conditions, making them suitable for both relaxed cruising and intense racing.

3. What makes Soling Sailboats stand out? One standout feature of Soling Sailboats is their fixed keel, which provides stability and allows for better upwind sailing performance compared to boats with swing keels or centerboards. This, combined with its powerful sail plan, grants the crew excellent control over the boat.

4. Can I solo sail a Soling Sailboat? While it’s possible to sail a Soling alone, it’s primarily designed as a three-person boat with easy handling and teamwork in mind. However, experienced sailors might enjoy the challenge of sailing solo on occasion.

5. Are there different classes or versions of Soling Sailboats? No, there is only one class of Solings recognized worldwide, ensuring fair competition across all races. While modifications are allowed within certain limits set by the International Soling Association (ISA), this ensures that boats remain relatively equal in terms of speed potential.

6. How fast can a Soling Sailboat go? Solings can achieve impressive speeds depending on wind conditions and the skill of the crew. The top speeds recorded by Soling Sailboats range from 7 to 14 knots, delivering a thrilling experience for sailors and spectators alike.

7. Is maintenance for Soling Sailboats challenging? Like any boat, Solings require regular maintenance to keep them in top condition. However, thanks to their simple rigging and design, maintaining a Soling is relatively straightforward compared to more complex sailboats.

8. Can I race a Soling Sailboat? Absolutely! Racing is the heart of the Soling class. Whether you’re an experienced racer or just starting out, competing in local or international events will provide endless excitement and opportunities to improve your skills.

9. Are there any famous sailors associated with Solings? Yes, several renowned sailors have made their mark within the world of Solings. The most notable being Poul Richard Hoj-Jensen from Denmark who won four Olympic medals in this class during his career.

10. Where can I find Soling Sailboats for sale? If you’re interested in owning a Soling Sailboat, there are various websites and forums dedicated to buying and selling sailing boats where you can find listings specifically for Solings. Connecting with local sailing communities is also an effective way to explore available options.

We hope this blog has provided informative and entertaining answers to your top FAQs about Soling Sailboats. Whether you’re intrigued by their design or considering racing one yourself, exploring the world of Solings will undoubtedly be an unforgettable adventure on the water!

Exploring the Anatomy of a Soling Sailboat

Welcome aboard, fellow sailors and sailing enthusiasts! In today’s blog post, we’re embarking on an exciting journey to explore the anatomy of a Soling sailboat. The Soling class has been cherished by many sailors worldwide, and understanding its components is vital for both beginners and experienced sailors alike. So, let’s dive in!

1. Hull: The Soling’s hull serves as its foundation, making it one of the most critical parts of the boat. Usually constructed from fiberglass or wood, the hull contributes to stability and buoyancy while also determining its speed capabilities. With sleek lines and a streamlined shape, the Soling hull effortlessly slices through waves, giving you an exhilarating ride.

2. Keel: Situated beneath the hull is the keel – a large fin-like structure responsible for maintaining stability and preventing excessive sideways drift (also known as leeway). The keel acts as a counterbalance against wind forces, allowing you to maintain control even in gusty conditions. Its intricate design ensures optimum performance against varying water depths.

3. Rudder: At the opposite end of the boat sits the rudder – your ultimate steering control system. Connected to the tiller or steering wheel inside the cockpit, this cleverly designed appendage enables precise maneuverability by redirecting water flow under pressure. With efficient rudder adjustments, you can smoothly navigate through tight turns or confidently stay on course wherever you choose to sail.

4. Mast: Standing tall and proud above deck is the mast – a symbolic centerpiece that gives your Soling sailboat its distinctive charm. Typically made of aluminum or carbon fiber, this vertical support holds up your sails while providing structural integrity to withstand powerful wind gusts. A carefully balanced rig tension makes all the difference between exhilarating speed and handling challenges.

5. Sails: Ahoy matey! Our attention now turns towards arguably one of the most captivating aspects of sailing – those elegant sails billowing in the wind. The Soling features a mainsail, jib, and spinnaker. The mainsail, positioned directly behind the mast, provides basic driving force. Jibs are smaller triangular sails located at the bow, manipulating airflow to assist in steering. Finally, the spinnaker is a large, colorful sail hoisted when running with the wind from behind – it’s like unleashing your boat’s hidden superpower!

6. Rigging: While less noticeable than other components, rigging plays an essential role in maintaining the overall integrity of your Soling sailboat. Consisting of wires or ropes that support the mast and sails, proper rigging tension ensures optimal control and performance by distributing forces evenly.

7. Cockpit: Ahh…the captain’s domain! The Soling’s cockpit serves as your sailing command center for safe navigation and tactical decisions during races or leisurely cruises. Equipped with various controls such as sheets (ropes that trim the sails), winches for easier line handling, and a compass to stay on course – this area reflects both functionality and style.

8. Trampoline: Picture yourself lying down on a horizontal mesh enjoying the refreshing spray of water below you – welcome to the world of Soling trampolines! Stretching across its foredeck platform between hulls, these net-like surfaces provide additional seating options while reducing weight aloft.

So dear sailors, as we disembark from our exploration into the anatomy of a Soling sailboat, we hope you have gained valuable insights into its intricate components that make this class so beloved among sailors worldwide. Remember though – sailing is not merely about understanding these parts individually but rather their harmonious collaboration to create an unforgettable experience on water. Bon voyage!

Soling Sailboat Maintenance Tips and Tricks for Longevity

Title: Unlock the Secrets to Longevity with Soling Sailboat Maintenance Tips and Tricks

Introduction: As passionate sailors, we understand the profound connection one can foster with their beloved soling sailboat. These graceful vessels have the power to transport us, both physically and emotionally, as we navigate the vast expanses of open water. To ensure our sailboats retain their splendor for years to come, it is crucial to prioritize regular maintenance and utilize a few clever tricks unique to soling sailboats. In this blog post, we present you with a comprehensive guide on soling sailboat maintenance tips and tricks that will guarantee longevity while injecting a dash of wit along the way.

1. Protect Your Hull’s Integrity: The hull serves as the backbone of any sailboat, including your trusty soling. To preserve its integrity, start by regularly inspecting it for any signs of damage or wear. Stickler for cleanliness? Give your hull some love by washing away salt residue after each voyage using a mild detergent solution – remember; cleanliness equals longevity!

2. Befriend Your Mast: Your mast is more than just an accessory; it holds immense significance in maintaining overall stability on the water. A witty trick here is to apply a thin layer of high-quality wax on your mast’s surface to reduce friction while lowering the chances of saltwater corrosion. This simple step significantly prolongs the life of your mast.

3. Rigging Reinvented: Ensuring your rigging remains in top shape is pivotal towards smooth sailing adventures aboard your soling sailboat. Maintain solidity by frequently inspecting wires and ropes for fraying or unwelcome visitors like rust or corrosion (cue hilarious “Sailing Bug Wanted” poster!). Licorice enthusiasts may find delight in applying an effective licorice gel coating around any fittings to keep rust at bay – who knew candy could save your rigging?

4. The Power of Lubrication: Winches, blocks, and cleats – the unsung heroes of a sailboat’s efficiency and success. To keep these pivotal elements in working order, lubricate them periodically with marine-grade lubricant. Ensure the universe aligns your witty moments by lubricating pun-free; too much grease hilarity might take away from the sailing experience!

5. The Devil in the Details (of Teak): Oh teak, you may be stunning, but maintaining your luster is an art form unto itself. Keep your soling sailboat’s teak deck looking dashing by regularly scrubbing it with a soft-bristle brush and mild detergent solution. Treat the wood to a spa day with teak oil or sealant every couple of years – pampered wood rewards you with longevity.

6. A Checklist for Trailer Queens: For those who care for their soling sailboats on land rather than rocking waves, never underestimate the importance of proper trailer maintenance. Check tires for cracks or signs of wear, inspect brakes diligently (no need to sniff out fouls here!), and keep an attentive eye out for loose fittings or rust formation. A well-maintained trailer ensures your vibrant sails touch every conceivable horizon.

Conclusion: In conclusion, granting your soling sailboat a long life requires diligence, care, and a sprinkle of wit along the way. By following these maintenance tips and tricks tailored explicitly for soling sailboats, you can navigate any sea with confidence while soaking up memories that will last a lifetime. Remember: regular inspections offer peace of mind amid tempestuous voyages and allow witty sailors to truly embrace their inner jokester without compromising durability!

Taking Your Soling Sailboat to New Heights: Advanced Techniques and Strategies

Welcome to our blog section where we delve into the exciting world of sailing and explore advanced techniques and strategies to take your Soling sailboat to new heights. In this blog post, we will equip you with professional insights, clever tactics, and witty anecdotes that will help unleash your inner sailor extraordinaire. So buckle up and get ready to set sail!

1. Mastering Wind Dynamics: Understanding the wind is paramount when it comes to sailing success. Delving beyond the basics of wind direction and speed, advanced sailors must learn about true wind versus apparent wind, how wind shifts affect boat performance, and how to optimize their sails for maximum speed in various wind conditions. By mastering these concepts, you’ll be able to navigate through even the trickiest winds like a seasoned pro.

2. Fine-Tuning Sail Trim: A crucial aspect of sailing excellence lies in the ability to fine-tune your sail trim as conditions change. An advanced sailor knows that minute adjustments can make all the difference in boat performance. We’ll cover topics such as proper sail shape, cunningham use for flattening the mainsail in heavy winds, vang tension adjustment for better control over leech tension, and genoa trimming techniques for optimizing speed while pointing high into the wind.

3. Perfecting Boat Balance: Achieving optimal boat balance ensures smoother handling and greater speed on the water. We’ll explore how adjusting weight distribution (crew placement) affects overall stability and maneuverability during different points of sail – upwind, downwind, or reaching. Additionally, we’ll discuss techniques such as heel angle management for maximizing forward propulsion without sacrificing control.

4. Tackling Upwind Tactics: When competing or navigating upwind stretches like a champ isn’t enough anymore; it’s time to delve into advanced upwind tactics! This section covers advanced techniques such as using telltales effectively for trimming sails based on airflow patterns rather than gut instincts alone, proper weight shifting during tacks, utilizing strategic maneuvers such as roll tacks or ducking to gain tactical advantage over competitors, and understanding the optimal angles of sail for efficient upwind progress.

5. Expanding Downwind Performance: Riding the wind on downwind legs can be exhilarating, but it requires a different set of skills altogether. To take your Soling sailboat to new heights, we’ll delve into advanced techniques like using symmetrical and asymmetrical spinnakers effectively, understanding gybing techniques that minimize speed loss and maximize overall velocity made good (VMG), mastering various downwind sail trim variations based on wind angles and sailor preferences, and implementing strategic tactics like surfing waves or performing controlled broaches for tactical gains.

6. Navigating with Precision: Advanced strategies demand precision navigation skills. In this section, we will discuss sophisticated methods for better course management using electronic navigational aids like GPS chartplotters or smartphone apps complemented by traditional dead reckoning. We’ll also touch upon leveraging tide tables and current predictions to optimize your route planning and gain an edge in both racing and cruising scenarios.

7. Race Day Mindset & Strategies: For those looking to take their Soling sailboat to competitive levels, a winning mindset is crucial. We’ll guide you through mental preparation techniques that help maintain focus amid intense race scenarios or long-distance challenges. Additionally, you’ll learn race-specific strategies such as starting line approaches, mark rounding tactics while jockeying for position with other boats, utilizing tactical coverings or forcing opponents into unfavorable positions – all in pursuit of crossing the finish line first!

So there you have it! Our detailed exploration of advanced techniques and strategies to elevate your sailing game with a Soling sailboat. Armed with professional insights along with our cleverly crafted tips and tricks, we invite you to embark on this thrilling journey that will undoubtedly transform you into a skilled sailor capable of navigating any challenge thrown your way. Fair winds and smooth sailing!

Recent Posts

- Sailboat Gear and Equipment

- Sailboat Lifestyle

- Sailboat Maintenance

- Sailboat Racing

- Sailboat Tips and Tricks

- Sailboat Types

- Sailing Adventures

- Sailing Destinations

- Sailing Safety

- Sailing Techniques

The Soling Class History

The Soling history actually began in the mind of Jan Linge during the late 50’s while he was doing design work and tank testing on a 5.5 metre to be built for a Norwegian friend for sailing in the 1960 Olympics. The friend, Finn Ferner, was a successful businessman and an outstanding helmsman, an Olympic medallist and winner of many international events. Linge had become convinced that a slightly smaller boat with a detached spade rudder and short keel could be a fast seaworthy boat with the likelihood of great popularity – though such features were not allowed under the 5.5 rules.

After 1960 Linge completed his design sketches to demonstrate his ideas for promoting a Norwegian national class. These seeds fell on barren ground for about two years, while the IYRU was reaching a decision to encourage more international classes – to take advantage of the research and materials developed during World War II, then becoming available for new domestic products – materials like plastics, synethetic yarns, glass fibre, as substitutes for wood and cotton.

IYRU seeks new classes

By the time of the 1961 IYRU meetings, the forces for change had organized themselves to seek four new classes – a single hander as companion to the Finn, a two-man keelboat to complement the Star, a three-man keelboat like the 5.5 or Dragon, finally a catamaran. The FD already had its companion in the 5 0 5., so there was no need for another centreboarder – 470’s, Lasers and Sailboards were to come later.

There was to be a step-by-step process, starting with an announcement in a prominent yachting magazine willing to monitor a class, with generalized dimensions; then there would be a design competition not to choose a boat but to allow the IYRU to illustrate the type of boat desired. Thereafter, the IYRU would hold trials under the supervision of a “Selection” Committee which it would appoint.

High performance and popularity

The underlying goals for these new boats was not explicit, but hinted: “high performance” and “popularity” were key words for whatever boat was chosen. There was sentiment among some countries, particularly those not performing well in existing classes, that new classes might displace existing ones in Olympic competition, though it was vigorously denied, perhaps out of political wisdom. Some thought the IYRU had a leadership role for promoting changes, others believed that international status should depend first on substantial levels of sailing activity around the world – i.e. a class already popular. The boats sought were all to be designated “Group A”, that is the group from which Olympic classes were picked.

The two-man keelboat process started in 1962 under the auspices of the Dutch sailing magazine “De Water Kampleon” with the announcement of the design competition, to culminate at the 1963 IYRU meetings, and Trials perhaps in 1965.

A design competition by the IYRU

It was the public announcement by the Class Policy Committee (CPOC) in mid 1963 that started events leading to the adoption of the Soling’s Olympic status four years later. The American magazine “Yachting” undertook to accept design sketches for presentation at the November 1963 meeting. “It should be a wholesome boat capable of being sailed from port to port in open water” – not “an extreme type design”, reported “Yachting” – “What IYRU wants is a nice compromise between maximum speed and maximum seaworthiness, with a good measure of both. The boat should certainly be non-sinkable and have built-in buoyancy, and should be capable of racing in open sea conditions. Since it is to be a racing boat, our guess is that an entirely open cockpit, or at most, a minimum caddy, would be most acceptable”. Obligatory maximum limits “LWL 22 feet, Draft 4’6″, Displacement 3799 pounds, Sail area 310 sq. ft.”

A boat for strong winds and heavy weather

At the November meeting, Linge, then a member of the Keelboat Committee, was armed with his plans and arguments for a smaller boat, cheaper, as much fun to sail and much easier to trail. A majority, however, favoured the larger boat – more like a one-design equivalent of the 5.5. A panel of three was appointed to be judges of the competition: Peter Scott (then President of the IYRU), Jan Linge and Rod Stephens, soon to become the world’s leading naval architect of ocean racing yachts. This group took most of the year before, in November, awarding modest prizes (US$300 for first) to the top three designs. Stephens wrote a summation of the judges’ thinking (“Yachting” January 1965) with this significant observation: “There is so much merit in the fibre glass construction … in providing uniformity of hull form (!)”. He went on to say: “In evaluating the designs, the judges tried to think in terms of use under widely varying conditions. It was felt that prize-winning designs – one or more of which may be ultimately used in a widespread one-design class – should be suitable for almost any kind of wind and sea conditions. In a way, this became a bias toward a boat suited to strong winds and relatively heavy weather simply because a boat of this sort is at least safe and useful in light weather, even if it is at its best as a racing boat only in stronger winds”.

The Linge/Ferner prototype

Once Linge had lost his argument at the 1963 meetings for a small boat, he returned to Norway determined to develop his version of a three-man keelboat. His next door neighbour, Sverre Olsen (See S.O. + LING), a successful merchant who had taken over the insolvent Holmen boatyard, became interested in backing the effort as useful publicity for his establishment. Given such resources, a wooden prototype was built, for experimenting with sizes and placement of rudders, keels, and rig. Finn Ferner, the champion skipper and Linge’s 5.5 client of 1960, became an important skilled partner in this activity. By mid 1965, Linge and Ferner were satisfied enough with their work to manufacture mold needs for producing complete fibre glass boats. In November 1965, the IYRU scheduled trials to be held off Kiel during September 1966, but for reasons not certain (perhaps to enlarge the entry list), allowed smaller boats provided “they were well ballasted, not a planing type”.

1966 Trials – Shillalah and the Soling

The high performance revolution was underway: The Tempest was given recognition, Catamaran trials were set for 1967, and a 1966 re-run of the single hander event which had had no wind in 1965 was held. During the Winter of ’65/’66, five fibreglass Solings were built which were extensively sailed against one another during the following Summer. This competition was destined to be helpful in the heavy weather ahead at Kiel – chosen as a windy challenge for what the IYRU desired.

The Norwegians arrived in Kiel with two boats – one to be raced, the other to remain on its trailer ashore available for inspection. Ferner was the helmsman, Linge and Rudolph Ugelstad the crew. There were eight boats, all prototype one-offs except for the Soling. The first race was in moderate air, but thereafter for ten of the eleven races, Kiel lived up to its breezy reputation.

The final race may have been worth all the rest for the Soling: a meeting of helmsmen gathered in view of the forty knot wind. Not surprisingly, the Committee’s desire to race was persuasive. On the way to the starting area, breakdowns and one sinking left but two to compete. By the windward mark only the Soling was left to sail the course, and so was able to demonstrate her outstanding ability to handle heavy air. The Selection Committee, consisting of Frank Murdoch (Chairman, Holland), Beppe Croce (Italy), Bob Bavier (US), Costas Stavridis (Greece), Sir Gordon Smith (UK) and Hans Lubinus (Holland)) was impressed.

Two boats were recommended: Shillalah, designed and sailed by US Starboat Champion, Skip Etchells, and Soling, the boat referred to as “the undersized entry”. Shillalah won eight of the ten races she entered – her speed was outstanding; although the Soling was about a foot and a half less on the water line, three feet less overall, 7% less sail area, she averaged a little over two minutes behind first place – was never outclassed, was good in rough weather, and was very fast on the reaches. Three months later in London, the CPOC endorsed the Selection Committee’s recommendation, but wait: “The Permanent Committee seemed on the verge of approving this recommendation without any dissent when one of its members who had an unsucessful entrant in the trials expressed the view that the trials were inconclusive because of insufficient variety in weather. Others then cast doubt as to whether Shillalah could be built in fibreglass at a weight comparable to the wooden prototype and if not how might she perform? Despite some assurance that she could be, the damage was done and all of a sudden a number of people who minutes before were all in favour of encouraging both boats, decided instead to delay until additional trials could clarify the matter” – wrote “Yachting” in January 1967.

1967 – Second Trials at Travemunde

So, more trials were scheduled – this time in Travemunde at the end of the 1967 Summer. A Committee now called “Observation” rather than “Selection” was this time chaired by Jonathan Janson (UK) with Beppe Croce (Italy), Ding Schoonmaker (US), Eddie Stutterheim of Holland and Hamstorf from Germany.

While the IYRU proceeded with deliberate speed, the ’66 Trials had generated action in Norway. The three promoters, Linge, Ferner, and Olsen, formed Soling Yachts A/S to build and sell the boats and to license builders. Paul Elvstrom obtained a boat for testing and sailing in the ’66/’67 Winter; he became an enthusiastic supporter. Even before the second (1967) set of Trials, some sixty boats were sailing in Scandinavia – a “local” class, even without international status.

Several new boats, a fibreglass Shillalah, also a 5.5 and a Dragon to compare speeds, assembled in Travemunde for the second Trials – this time in what became a moderate air series. Again Shillalah was the big winner, but again Soling finished respectably. This time she was sailed by Per Spilling (destined to win the first European Championship in 1968) with Sven Olsen and Linge again as crew. Without comment, the Observation Committee recommended Soling alone; this result passed unanimously through the IYRU meetings. The Soling had become an international class, but not without the help of the Norwegian Embassy where hitherto non-existent Class Rules were put together one Friday night by Beecher Moore (subsequent host of many Soling parties), Jan Linge and Finn Ferner, and then reproduced by the Embassy staff just in time for the Saturday morning meeting of the CPOC.

Soling gets chosen

Needless to say a celebration was in order. The supporters of Shillalah could grumble about European politics and IYRU’s misleading campaign for a big boat, but the Norwegians hit the town for an all night blast, with the blessings of a friendly innkeeper selling his brew long after closing hours – one snag: the bill, product of the hours of carousel by fifty happy people unprepared to pay. The innkeeper was willing to wait for his money until Soling Yachts A/S could return to Oslo – a short time, but enough for a 40% drop in the British pound; so the party had been a bargain!

New Olympic Class

The 1968 Games in Mexico were held before the Class acquired its Olympic status. Because there was a five-class limit set by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the CPOC had recommended 5.5, Soling, Tempest (its two new boats), FD and Finn – these at the cost of Dragon and Star. The Permanent Committee was heavily lobbied by Dragon enthusiasts and so dumped the 5.5; in the same process the Star owners forced abandonment of IYRU’s Tempest. It took another four years after the ’72 Games for the Soling to become the single three-man keelboat, when the Dragon was finally retired.

In April of 1969, after this bloody battle, the IOC relieved the pressure on the IYRU by allowing a sixth “event”. When the IYRU added the Tempest, a fourth keelboat out of six, sailors throughout the world of small boat racing rose up in fury at the keelboat bias by the elders of yachting. These events, while not quite germane to Soling history, describe the dynamics of IYRU decision making when Olympic classes are changed.

Solings multiply

The news of the Trials’ results not only assured the Soling’s status, but stimulated a building spree: three hundred in 1968 and as many or more in 1969. Elvstrom became the dominant builder in Europe, particularly after he won the first Soling World Championship off Copenhagen in 1969. One of the best American helmsmen, George O’Day, was given a licence to build for the US market, just as Bill Abbott Sr. acquired the Canadian market.

Bill Abbott

Since Abbott, alone of the original builders, has remained a steady supporter of the class and was to become the producer of more Solings than any other world wide, his own story bears telling. The “Chief” (as he is now known in all the hemispheres) had been looking for a small racing boat in 1966 to build in fibreglass for the use of local sailors at the southern end of Lake Huron. Pictures of the Soling competing in the ’66 Trials showed such a boat, and it attracted him as a solution to his search. After negotiations with Jan Linge, who preferred to sell boats rather than license them, Abbott bought a plug which arrived in June of 1967. Molds were then built so that six boats were produced by the end of the year – at a leisurely pace, because Abbott was unaware of the pace of developments at the IYRU. But in 1968, be built 40, 129 in 1969, and then up to one per day as the American market opened to his benefit. Abbott had struck oil without looking for it.

Not all fibreglass boats are identical

It was clear by 1969 that the Soling had arrived. Now it was essential that a responsible class be formed to govern, to encourage measures for its safety and to adopt restrictions against expensive “improvements”. But more important, the class had to control the shape of the hull, keel and rudder. The effort continues even today. Class Rules were therefore a priority, and were built upon those assembled by Linge and Ferner in 1967. Uniformity, the unrealizable goal of one-design mystique, was assured in the Sixties to have been accomplished by fibreglass construction. Experience was to prove a different reality. That called for vigilance by Class Officers.

Many influences were at work even as the Soling was brought into existence. Sailcloth in dacron became available as the replacement for the best Egyptian cotton by 1960, but it took a few years for sailors to learn the significance of draft location and how to adjust it underway. To do that required an assortment of marine hardware for the creation of systems of control. Compare, for example, the vang (alias, kicking strap) of 1968 with its 5:1 advantage tackle to the multi-block 25:1 arrangements on today’s boats. Harken and Holt among others arrived in time to make the Solings a sophisticated boat just as complexity was converting the sport into more science and head work. Leading sailors like Elvstrom were the first to grasp the potential for these developments in boat speed. The Class Rules had to ensure a measured pace.

Paul Elvstrom

The first World Championship was won by Paul Elvstrom in a boat named Bes, one of three Norwegian boats built in 1968. Elvstrom spent much time testing his idea, while “customizing” three of these boats – one for himself, one for King Constantine, and one for Erik Johansen, a fellow Dane.

One Design challenge

Said one knowledgeable sailor: “Paul Elvstrom’s boats tested the limits of the Soling class in every direction” (see Article by Graham Hall, “One Design and Offshore Yachtsman”, November 1969, now known as “Sailing World”: 3 pages of detailed photos and comments). When measured and protested “on general principles”, Elvstrom’s boats were faulted on only one point: he “had raised the floor about ten inches and had fibre glassed them to the inside of the hull, making an effective double bottom”. With “Elvstrom bailers”, the boat was self-bailing. The floorboards were deemed to be “overweight”; holes were required to be drilled so that water in the cockpit could collect below in the bilge and be pumped like the rest of the fleet. The article concluded:

“Whenever a boat like Elvstrom’s makes such an impression on a class, there always emerges a re-written set of rules dealing with the major “loopholes” that allowed the development. Such was the case with Buddy Freidrich’s Dragon after the 1967 Worlds in Toronto. The newly elected International Soling Class technical committee will have to deal with any questions that the 1969 Worlds have brought to light. Chief among them will be rulings on floorboards and double-bottoms, hiking straps, devices, handles, hull weight, builder inspections, template enforcement, underwater keel location, and flush-hulled rudders. Recommendations of the ISA technical committee will be forwarded to the IYRU technical committee to ensure that the rules reflect accurately the intention and design of the original boat as adopted by the Union.

The answers to these questions will tell whether and how far the Soling class is actually going in a “one-design” direction. “The thing that bothers me”, George O’Day said at breakfast during the Worlds, “is that we have reached a stage where unless the class makes some far reaching decisions, people won’t buy into it”.

Melges makes the boat “simple”

While the Elvstrom boat of 1969 seemed a miracle of ingenuity that year, it nevertheless offered an extraordinary contrast to the Melges boat of 1972 in which Buddy Melges won the Class’ first Olympic gold medal. The drums used in Elvstrom’s boat to provide mechanical advantage at either end of the cockpit, the centre horse, the four big winches for trimming the jib and spinnaker, the clutter of lines coming into a console at the forward end of the cockpit, the spider web of shock cord to raise the spinnaker boom, the free standing handles on each rail for the crew, the tracks to change clew positions, and even the shroud tracks – all became victims of the Melges systems below decks or behind the bulkhead hatches. Marine hardware had come of age between the Elvstrom boat and Melges’.

The value of the raised floor (now called the cockpit sole) as an essential element in the construction and sailing of the Soling is apparent to anyone in 1996, but it was not in 1969. The ISA meeting of that November adopted it only after a tie compelled Bill Abbott to cast a deciding vote after overnight thought. His agony was in Canada where twenty unsold boats had been built without those floors.

The cockpit sole

A committee of IYRU technical people with help from the class was left to re-draft the rules which could be used by sailors preparing for the 1972 Games. Elvstrom had more ideas for strengthening the boat with support from the floor downward rather than have it rest upon members built up from the keel. He attempted to get IYRU approval without success, but went ahead with his plan in the sixty boats he built in 1970. Although his ideas were ultimately allowed “he had his knuckles slapped”. IYRU too had difficulty in this age of fibreglass: the templates made by the IYRU for the 1972 Games created a major problem because many boats built by licensed builders with approved tooling did not fit – fibreglass construction was more complicated than making muffins.

Jack Van Dyke

It was in this state of confusion that on 1st January 1973 Jack Van Dyke, the then President of the US Soling Association, succeeded Eggert Benzon as ISA President. In 1972 the Soling had been redesignated as an Olympic Class, looking towards the ’76 Games. But the signals at the IYRU were to shape up with better control over the boat’s construction, as well as its potential for high cost improvements contrary to the intention of Section 1 of the Class Rules.

Van Dyke’s previous years with the IYRU helped to make 1973 a watershed year. A “Measurement Seminar” was held in Genoa with the IYRU’s new President, Beppe Croce, Nigel Hacking (Executive Secretary), Tony Watts (IYRU Chief Measurer) and others, for a new and successful effort to tame the tigers of creativity. Since then the class has been able to confront problems, one by one, as they arose. There proved to be many down the years: hiking devices, shroud tracks, jib self tackers, reinforcement of the mast step area, rudders shaped by templates, sail inventories, steps to ensure watertight compartments, more keel templates to discourage excessive fairing and keel shaping contrary to the rules.

Old Friends at the 20th Birthday Party

In 1985, the Class held a birthday dinner party to celebrate its twentieth anniversary. Present to celebrate with us was the late Beppe Croce, then President of the IYRU; and the Chairman of the CPOC during the turbulent years of our birth – Jonathan Janson – who was also Chairman of the 1967 Observation Committee who recognized the beauty of the little boat Jan Linge had designed; and King Constantine of Greece, a competitor at our first World Championship.

HRH King Harald

In 1991 HRH King Harald of Norway graciously accepted the Class’ invitation to succeed his father as Honorary President and he has been extremely supportive of the Class’ aspirations.

Since Jack Van Dyke the ISA has had seven Presidents: Geert Bakker – 1976-1979, Ken Berkeley – 1980-1982, Karl Haist – 1983-1986, Sam Merrick – 1987-1990, Stu Walker – 1991-1994, George Wossala – 1995-1998 and Tony Clare the current President. During this period the major themes of the Class have been the strengthening of its Class Rules to ensure the maintenance of its “one-designedness”, the continuance of its Olympic status (often against significant opposition), the promotion of match racing, and the support of events and opportunities that bring club sailors and Olympic aspirants together.

Geert Bakker

Geert Bakker provided a transition that led the Class from its pioneer days to its pre-eminence as the world’s most active and admired three-man keelboat. Katrina Bakker says that she knows how much (her husband) Geert (who died far too young in 1992), “loved the Soling Class and what great pleasure it gave him to be President”. Geert was elected to the Presidency in 1976, the year he represented The Netherlands in the Kingston Olympics.

Ken Berkeley

Match racing became a regular feature of the Class’ European schedule in 1983 when Ken Berkeley (who had just retired) donated a trophy for annual competition based upon experience over several years on Lake Balaton in Hungary and in Berlin. Ken Berkeley recruited the present Secretary in 1980 after the death of Eyvin Schiotz who had been Secretary since the early years of the Class.

Karl Haist had been President of the large and enthusiastic German Soling Class before he became the first central European President of the ISA. He encouraged East Germany (then the DDR) to become more active in the regular events of the Class and arranged for the first European Championship behind the “Iron Curtain”. Karl was particularly concerned to maintain the one-design character of the boat and during his tenure additional templates were introduced to control the shape of the keel. As the number of entries in championship events had become excessive, Karl devised a quota system that assured the participation was equitably distributed amongst the nations. Heike Blok brought forward the concept of an international ranking system and donated the Soling World Trophy.

Sam Merrick

During Sam Merrick’s Presidency the IYRU heirarchy launched a major programme to make sailing a spectator sport, part of which was to introduce match racing into the Olympics. Sam persuaded the Class and the IYRU that if match racing were to be introduced, the ideal means was to use the Soling in a fleet/match event and he presided over the establishment of the present Olympic format in which the top fleet racers advance to a match racing final. The first Soling manual (a guide to racing the Soling), edited by Heike Blok, was published and distributed to all Soling sailors. The number of sails allowed in a regatta was reduced to one main, two jibs, and two spinnakers. Perhaps most importantly, Uli Strohschneider’s campaign to make the Soling unsinkable was successful and the Class Rules were modified to require that hatch covers be screwed into place. No Solings have sunk since this time.

Stu Walker campaigned successfully to keep the Soling in the ’96 Olympics and to continue the fleet/match format. Early in his Presidency the attempt of a builder to construct “Solings” using an illegal foam sandwich was detected and the builder’s licence was withdrawn. Stu established a strong, well organized Technical Committee that included the major builders and which has been successful in openly recognizing and solving problems before they become significant. As President, Liaison Officer, and Umpire, he actively promoted match racing in the Class, and developed with Mundo Vela Cadiz the Infanta Dona Cristina Match Racing Series as the premier match racing event of the Class.

George Wossala

George Wossala, as Vice-President and then President of the ISA, became a major influence in the Hungarian Yachting Association (he is President of the HYA), and subsequently was appointed to several important ISAF Committees. Thanks to his excellent links with ISAF (and with his ability to communicate in any one of a dozen or so languages) he was, and continues to be, instrumental in maintaining the status of the Soling Class as the Olympic fleet/match racer. During his reign as ISA President he also strove to improve the status of the Class’ club racers, while aspiring to, and achieving, an Olympic berth himself (in the 1996 Olympics). He has also instigated the first Soling Masters’ Championship – to be held at Lake Balaton in September 1999.

After serving as Chairman of the ISA Technical Committee from 1980 – 1998 and as Vice President (Administration) from 1990 – 1998, Tony Clare became ISA President in January 1999. He first became a Soling owner in the Seventies for the best possible reason – he saw it as a boat in which he could have tremendous fun racing against a hard core of like-thinkers based at his beloved Burnham-on-Crouch. And of course he was right. Tony is blessed with an enquiring and analytical mind which he has turned to finding out all about the guts of a Soling and what makes it go. He has spent an enormous amount of time and effort over the last 20 years to make the Soling machine work smoothly and to make the Class and its administration the most respected of all the Olympic classes.

Jean-Pierre Marmier

Another very long serving ISA worker, Jean-Pierre Marmier (Chairman of the ISAF Measurement Committee, and also appionted as the Chairman of the 2000 Olympic Regatta Measurement Committee), was the Class Chief Measurer from 1980 – 1998 and became Chairman of the ISA Technical Committee in January 1999. He keeps a very close eye on the Class Rules (and updated them to comply with the new ISAF standard class rules in 1997) and has always required competitors to adhere to the highest possible standards. He has been regularly attending ISA Committee meetings since 1977 (in the early days as a proxy, then sometimes as the Appointed member for Switzerland, and sometimes as an Elected member). We cannot imagine Committee meetings without his wise presence.

British Soling Association

Review of Soling

Basic specs..

The hull is made of fibreglass. Generally, a hull made of fibreglass requires only a minimum of maintenance during the sailing season. And outside the sailing season, just bottom cleaning and perhaps anti-fouling painting once a year - a few hours of work, that's all.

Note: the boat has also been sold to be self-made/-interiored, which means that the quality of each boat may vary.

The boat equipped with a fractional rig. A fractional rig has smaller headsails which make tacking easier, which is an advantage for cruisers and racers, of course. The downside is that having the wind from behind often requires a genaker or a spinnaker for optimal speed.

The Soling is equipped with a fin keel. The fin keel is the most common keel and provides splendid manoeuvrability. The downside is that it has less directional stability than a long keel.

The keel is made of iron. Many people prefer lead keel in favour of iron. The main argument is that lead is much heavier than iron and a lead keel can therefore be made smaller which again result in less wet surface, i.e. less drag. In fact iron is quite heavy, just 30% less heavy than lead, so the advantage of a lead keel is often overstated. As the surface of a fin type keel is just a fraction of the total wet surface, the difference between an iron keel and a lead keel can in reality be ignored for cruising yachts.

The boat can enter even shallow marinas as the draft is just about 1.32 - 1.42 meter (4.33 - 4.63 ft) dependent on the load. See immersion rate below.

Sailing characteristics

This section covers widely used rules of thumb to describe the sailing characteristics. Please note that even though the calculations are correct, the interpretation of the results might not be valid for extreme boats.

What is Capsize Screening Formula (CSF)?

The capsize screening value for Soling is 1.89, indicating that this boat could - if evaluated by this formula alone - be accepted to participate in ocean races.

What is Theoretical Maximum Hull Speed?

The theoretical maximal speed of a displacement boat of this length is 6.0 knots. The term "Theoretical Maximum Hull Speed" is widely used even though a boat can sail faster. The term shall be interpreted as above the theoretical speed a great additional power is necessary for a small gain in speed.

The immersion rate is defined as the weight required to sink the boat a certain level. The immersion rate for Soling is about 77 kg/cm, alternatively 434 lbs/inch. Meaning: if you load 77 kg cargo on the boat then it will sink 1 cm. Alternatively, if you load 434 lbs cargo on the boat it will sink 1 inch.

Sailing statistics

This section is statistical comparison with similar boats of the same category. The basis of the following statistical computations is our unique database with more than 26,000 different boat types and 350,000 data points.

What is Motion Comfort Ratio (MCR)?

What is L/B (Length Beam Ratio)?

What is a Ballast Ratio?

What is Displacement Length Ratio?

What is SA/D (Sail Area Displacement ratio)?

What is Relative Speed Performance?

Maintenance

When buying anti-fouling bottom paint, it's nice to know how much to buy. The surface of the wet bottom is about 15m 2 (161 ft 2 ). Based on this, your favourite maritime shop can tell you the quantity you need.

Are your sails worn out? You might find your next sail here: Sails for Sale

If you need to renew parts of your running rig and is not quite sure of the dimensions, you may find the estimates computed below useful.

| Usage | Length | Diameter | ||

| Mainsail halyard | 22.6 m | (74.0 feet) | 8 mm | (5/16 inch) |

| Jib/genoa halyard | 22.6 m | (74.0 feet) | 8 mm | (5/16 inch) |

| Spinnaker halyard | 22.6 m | (74.0 feet) | 8 mm | (5/16 inch) |

| Jib sheet | 8.2 m | (26.8 feet) | 10 mm | (3/8 inch) |

| Genoa sheet | 8.2 m | (26.8 feet) | 10 mm | (3/8 inch) |

| Mainsheet | 20.4 m | (67.1 feet) | 10 mm | (3/8 inch) |

| Spinnaker sheet | 18.0 m | (59.0 feet) | 10 mm | (3/8 inch) |

| Cunningham | 3.2 m | (10.5 feet) | 8 mm | (5/16 inch) |

| Kickingstrap | 6.4 m | (21.0 feet) | 8 mm | (5/16 inch) |

| Clew-outhaul | 6.4 m | (21.0 feet) | 8 mm | (5/16 inch) |

This section is reserved boat owner's modifications, improvements, etc. Here you might find (or contribute with) inspiration for your boat.

Do you have changes/improvements you would like to share? Upload a photo and describe what you have done.

We are always looking for new photos. If you can contribute with photos for Soling it would be a great help.

If you have any comments to the review, improvement suggestions, or the like, feel free to contact us . Criticism helps us to improve.

SOLING 1 METER

Class contact information.

Click below

Class Email

Class Website

One-Design Class Type: Radio Control

Was this boat built to be sailed by youth or adults? Both

Approximately how many class members do you have? 690

Photo Credit:AL Fearn

Photo Credit: Mike Wyatt

About SOLING 1 METER

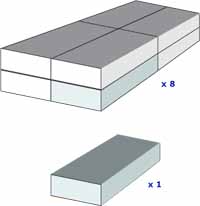

The Soling Class is the largest class affiliated with the American Model Yachting Association (AMYA). It is a one-design class. The One Meter was designed to be a low-cost, kit-based one-designed class primarily targeted at the beginning Radio-Controlled (R/C) sailor. It is often the local class that beginning sailors start with and yet it is challenging enough that most advanced racers still race their Soling. The hull, deck, keel, and rudder are made from vacuum formed polystyrene plastic. Only flat single-paneled sails are approved by the Soling Class. Only two channels are used to control the boat. One channel for both sails and the other channel for the rudder. Transmitter may have additional channels but they are not allow to be used in sanctioned races.

Boats Produced: Several thousand

Class boat builder(s):

Are in the process of selecting new builders. More to come in the future.

Approximately how many boats are in the USA/North America? 1000 +/-

Where is your One-Design class typically sailed in the USA? List regions of the country:

You can generally find a club that sails the Soling 1 Meter in all regions of the USA.

Does this class have a spinnaker or gennaker? No

How many people sail as a crew including the helm? 0

Ideal combined weight of range of crew: 0

Boat Designed in 1980s+/-

Length (feet/inches): 39.375″

Beam: 8.875″

Weight of rigged boat without sails: Minimum weight, ready to sail including batteries is 10lbs.

Mast Height:

Coaching or Clinic Resources

Class rules (pdf doc).

Back to One-Design Central

Copyright ©2018-2024 United States Sailing Association. All rights reserved. US Sailing is a 501(c)3 organization. Website designed & developed by Design Principles, Inc. -->

Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

Busting the hull speed myth

- julianwolfram

- December 13, 2021

Waterline length is not the defining factor in maximum boat speed that we all think it is. Julian Wolfram busts the hull speed myth

Modern hull forms, like this Jeanneau SO440, use chines to create volume forward while keeping a narrow entrance at the waterline

Every sailor is delighted when the breeze picks up and the boat really starts to get going with a bone in her teeth.

Julian Wolfram is a physicist, naval architect, former professor of ocean engineering at Heriot-Watt in Edinburgh and a Yachtmaster Offshore who has cruised and raced for 45 years

The crew will want to know how fast she will go and perhaps surreptitiously race her against any similar sized boat in the vicinity.

Speculation may start about what allows one boat to go faster than another – is it the hull shape or the sails?

It is easy to spot good, well-trimmed sails but what about the hull ?

The important part is not visible below the water surface. However there is one key indicator that is often very apparent – the waves generated by the sailing yacht.

When a yacht picks up speed the wave pattern around it grows and the greater the speed the bigger the waves .

The energy in these waves is proportional to the square of their height – double the height and the energy goes up by a factor of four.

This energy comes from the wind , via the sails and rig , making the hull push water out of the way.

If less of this wind energy was wasted in producing waves the yacht would go faster.

When a typical displacement monohull reaches a speed-to-length ratio of around 1.1 to 1.2 (speed in knots divided by the square root of the waterline in feet) up to half the wind energy driving it is usually wasted in generating waves.

The hull speed myth: Half angle of entrance

So how can we tell if a yacht will sail efficiently, or have high wave resistance and waste a lot of energy generating waves?

The answer starts back in the 19th century with the Australian J H Michell.

In 1898 he wrote one of the most important papers in the history of naval architecture in which he developed a formula for calculating wave resistance of ships.

Light displacement cruising boat: The bow of this Feeling 44 is finer than older cruising boats

This showed that wave resistance depended critically on the angle of the waterlines to the centreline of the ship – the half angle of entrance.

The smaller the angle the smaller the height of the waves generated and the lower the wave-making drag.

A knife blade can slice through water with minimal disturbance – drag the knife’s handle through and you generate waves.

The big hull speed myth

For a displacement hull the so-called ‘hull speed’ occurs when the waves it generates are the same length as the hull.

This occurs when the speed-length ratio is 1.34.

It is claimed that hulls cannot go significantly faster than this without planing. It is called ‘the displacement trap’ but is a myth.

Heavy displacement cruising boat: An older design has a bow that is several degrees wider

As an example, consider a 25ft (7.6m) boat that goes at 10 knots in flat water.

This is a speed-length ratio of two. That is the average speed over 2,000m for a single sculls rower in a world record time.

The reason for this high speed is a half angle of entrance of less than 5º. Hobie Cats, Darts and many other catamarans have similarly low angles of entrance and reach even higher speed-length ratios with their V-shaped displacement hulls.

These hulls also have almost equally fine sterns, which is also critically important to their low wave resistance.

The monohull problem

Now a monohull sailing yacht needs reasonable beam to achieve stability and, unless waterline length is particularly long, the half angle of entrance will inevitably be much larger than those on rowing skulls and multihulls .

In his 1966 Sailing Yacht Design Douglas Phillips-Birt suggests values of 15º to 30º for cruising yachts.

Many older cruising yachts with long overhangs and short waterline lengths, for their overall length, have values around the top of this range.

Busting the hull speed myth: A Thames barge is a similar length and beam to a J-Class, but its bluff bow, built for volume, makes it much slower. Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Newer sailing yachts, with plumb bows, have somewhat smaller half angles and a modern 12m-long fast cruiser may have a value around 20º and a racing yacht 17º or 18º.

Size matters here as, to achieve stability, a little yacht is likely to have a bigger half angle than a large one, such as the German Frers-designed 42m (138ft), Rebecca which has a half angle of entrance of under 13º.

Rebecca also has a fine, elegant stern which helps minimise the stern wave – I’ll come back to sterns and stern waves.

Interestingly the half angle of entrance is not mentioned in the otherwise excellent 2014 Principles of Yacht Design by Larsson et al, although it is currently used as one of the parameters in the preliminary estimation of wave resistance for ships.

While it is still particularly applicable to very slender hulls, naval architects are not generally familiar with Michell’s work.

His formula for wave resistance involves quadruple integrals of complex functions.

German-Frers’ designed Rebecca has a half angle of entrance of just 18°. Credit: Cory Silken

These are not ‘meat and drink’ for your average naval architect, and only a few mathematically inclined academics have much interest in theoretical wave resistance.

Michell’s work is rarely, if ever, covered in naval architecture courses now.

Nowadays the emphasis is much more on numerical methods, high-speed computers and computational fluid mechanics (CFD) using the so called Navier-Stokes equations.

Examining these equations, which apply to any fluid situation, does not give any insights into wave resistance, albeit they can model wave resistance very well when used in the piecewise manner of CFD.

It is very easy to measure the half angle of entrance at the design waterline when a yacht is out of the water.

Take a photograph directly upwards from the ground under the centreline at the bow.

Busting the hull speed myth: Multihulls achieve high speeds due to fine hulls, light displacement and ample stability. Credit: Joe McCarthy/Yachting Monthly

Now blow this up on a computer screen, or print it off at a large scale, and measure the angle with a protractor.

Alternatively, if you have a properly scaled accommodation plan drawn for a level close to the design waterline this will yield a reasonable approximation of the half angle of entrance.

Unfortunately there is not a simple relationship between the fineness of the bow and the wave drag.

But, all other things being equal, the smaller the half angle the better.

It is easy to measure and is a useful parameter to know when comparing yachts.

Stern shape and hull speed

The half angle of entrance cannot be taken alone as a measure of wave drag, and the fairness of the hull and in particular the run aft is also critical.

Just as the half angle of entrance dictates the height of the bow wave, so the fineness of the stern is a key influence on the height of the stern wave.

Consider the water flowing around both sides of the hull and meeting at the stern.

Modern race boats, like Pip Hare ‘s IMOCA 60, combine a fine angle of entrance with wide, flat hulls for maximum form stability and planing ability. Credit: Richard Langdon

If these streams meet at a large angle the water will pile up into a high stern wave.

On the other hand if they meet at a shallow angle there will be less piling up. A fine stern can maintain a streamline flow of water.

However if the sides of the hull meet at the stern at a large angle then the streamline flow will tend to separate from the hull, leaving a wide wake full of drag-inducing eddies.

Continues below…

How hull shape affects comfort at sea

Understanding how your hull shape responds to waves will keep you and your crew safe and comfortable in a blow,…

Boat handling: How to use your yacht’s hull shape to your advantage

Whether you have a long keel or twin keel rudders, there will be pros and cons when it comes to…

Sailing in waves: top tips to keep you safe at speed

Sailing in waves can make for a jarring, juddering experience and long, uncomfortable passages and at worst, a dangerous, boat-rolling…

How to cope with gusts and squalls

Spikes in wind strength can range from a blustery sail to survival conditions. Dag Pike explains how to predict which…

In many modern designs the hull sides are not far off parallel at the stern and it is then the upward slope of the buttock lines that are critical and, again, the shallower the slope the better from a hull drag perspective.

The slope of the buttocks can easily be measured if the lines plan is available and a good indication can be obtained from a profile drawing or a photo taken beam on with the boat out of the water.

Drawing a chalk line parallel to the centreline and half a metre out from it will provide a buttock line that can be checked visually for fairness when the boat is viewed from abeam.

A rowing scull easily exceeds its theoretical max hull speed. Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Again, the smaller the angle the better – provided the transom is clear of the water.

An angle of more than 17º will lead to separated flow and eddy making. This also happens if the transom is immersed.

The greater the immersion the greater the drag, so weight in stern lockers on modern boats can be critical.

Modern hull design

The modern wedge shape attempts to resolve the conflicting demands of a small angle of entrance, good stability and a fine stern.

The plumb bow extends the waterline forward and, with the maximum beam taken well aft, the hull forward can be relatively narrow, providing a low half angle of entrance.

The stern is wide, which helps achieve good stability, but at the same time the buttocks rise slowly at a shallow angle to the water surface.

This gives a smooth and gradual change in the hull’s cross section area ensuring the water flow remains attached to the hull and that the stern wave is kept low.

A modern cruising boat gains stability from a wide stern, but needs twin rudders

This wide, flat stern also helps surfing down waves and possibly planing.

Some designs have chines just above the design waterline which increases usable internal volume and gives a little more form stability when heeled.

However, as soon as the chine is immersed there will be separation along the chine edge as water will not flow smoothly around a sharp edge.

It is just not possible to get the chine perfectly aligned with the streamlines of the water flow in all sailing conditions and there will be some extra drag at times.

There are two downsides to the wedge- shaped hull.

Overloading aft will create a large increase in drag

First the boat has to be sailed at a small angle of heel to keep the rudder properly immersed and to avoid broaching. This can be offset to some extent by using twin rudders .

The second is that the weight must be kept relatively low.

This is because a relatively small increase in weight causes a big increase in wetted surface area at the stern and hence in the frictional drag which makes the boat slower, particularly in light airs.

This is the downside of slowing rising buttocks and the reason why dinghy sailors get their weight forward in a light breeze .

Displacement Length Ratios

Traditionally for sailing yachts the displacement-length ratio has been used as a measure of speed potential, partly because it is easy to calculate from the yacht particulars.

It is waterline length (in metres) divided by the cube root of displacement (in cubic metres or tonnes).

A heavy boat, such as the Heard 35, will have a value of about 4 to 4.8.

A more moderate displacement boat, such as the Hallberg Rassy 342 or Dufour 32 Classic, will have a value in the range 5 to about 5.5; whilst a racing boat may a value of up to, and even over, 7.

A heavy displacement cruising boat with a fair run aft is less affected by additional weight

However the displacement length ratio can be misleading as making a hull 20% deeper and 20% narrower will keep the displacement the same but will significantly reduce the half angle of entrance and the wave drag.

It is interesting to note a Thames barge in racing trim has the same length-displacement ratio as a J class yacht, but their speed potential is vastly different.

Finally I should mention the older ‘length-displacement’ ratio, which is quoted in imperial units.

This is calculated by dividing a boat’s displacement in tons (2,240 pounds) by one one-hundredth of the waterline length (in feet) cubed.

Credit: Maxine Heath

It is still used in the USA and should be treated with caution.

The myth that your boat’s speed is only restricted by it waterline length does a disservice to its designers, and does little to help you understand how to get the best from her when the wind picks up.

Have a look at how the boat is loaded, how you sail on the wind, your boat handling and how much canvas you ask her to carry and you may discover more speed than you expect.

The remarkable John Henry Mitchell

Pioneer of wave theory

It’s worth saying a little more about the remarkable John Henry Michell.

He produced a series of ground-breaking papers including one that proved a wave would break when its height reached a seventh of its length.

He was the son of Devon miner who had emigrated to the gold mining area near Melbourne.

He showed such promise that he got a scholarship to Cambridge.

He was later elected a fellow of the Royal Society at the age of 35 – not bad for the son of a Devonshire miner.

His brother George was no slouch either – he invented and patented the thrust bearing that is named after him.

The half angle of entrance became the traditional factor for assessing the fineness of hulls.

It is defined as the angle the designed waterline makes with the centreline at the bow.It varies from less than 5º for very fine hull forms up to 60º or more for a full-form barge.

At higher speeds, modest increases in the half angle can give rise to substantial increases in wave resistance.

Enjoyed reading Busting the hull speed myth?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price .

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals .

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram.

- Forum Listing

- Marketplace

- Advanced Search

- About The Boat

- Boat Review Forum

- SailNet is a forum community dedicated to Sailing enthusiasts. Come join the discussion about sailing, modifications, classifieds, troubleshooting, repairs, reviews, maintenance, and more!

soling sailboat

- Add to quote

hello all, i am looking at buying a soling sailboat and just had acouple of hang ups about it. can most 27' ish sailboat trailers hold a soling? i ask this because the person im looking to buy the boat off of whats an extra 1800 for the trailer and was thinking i could find it cheaper. or maybe thats a good price?has anyone heard of or have seen a small outboard motor on a soling? is dry sailing the best for this boat? i was also wondering if solings could be phrf raced? thanks, i promised i seached for these anwsers.

The cradle should be fitted to the soling hull, most I have seen use a solid support that fits the curve of the hull. In my area the solings are dry sailed, most owners are very particular about keeping the hull clean and waxed. I have never seen a motor on a Soling I think it could disrupt the balance and could make it difficult to get full tiller motion. Solings are very quick and agile race boats, not really a day sailor. On the trailer, what would the current owner use it for? Keep negotiating.